Tag: Edu-larp

-

Learning from Bleed

How you can learn from bleed yourself, and how you design a larp in such a way that your participants can learn from their bleed, if they want to.

-

Innovations in the Drama Classroom with Larp

in

Larp activities for middle school students born out of a focus on emergence.

-

Serious Larp at the United Nations in Geneva

Account of a Serious Larp run at the United Nations in Geneva, in which 30 staff played parents designing a new school for their children.

-

Designing Power Dynamics Between Adults and Children in Larps

in

A practice-based approach utilized in edu-larp and leisure larps, including a mythical fantasy campaign.

-

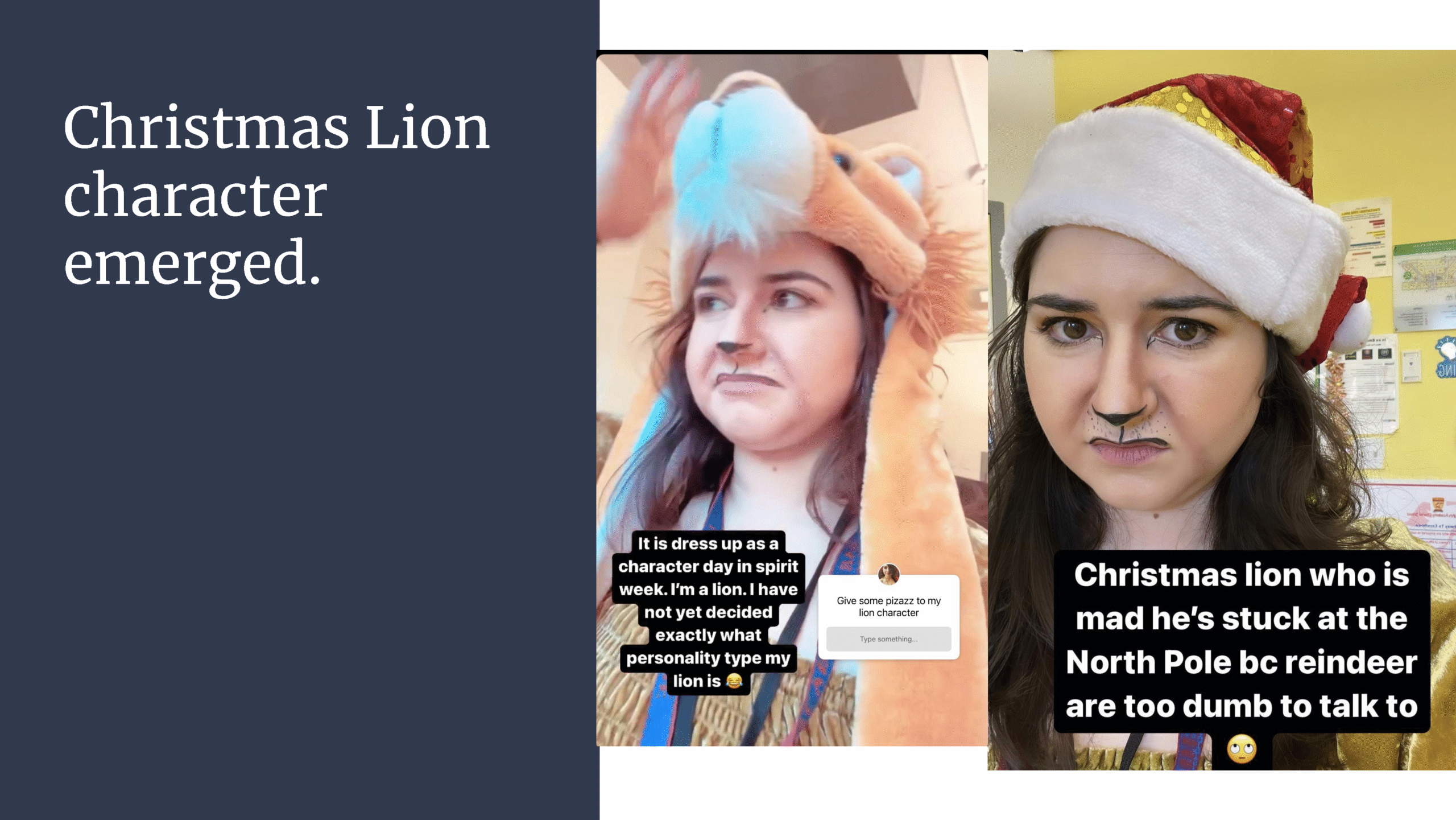

Adding Larp to a Drama Teacher’s Curriculum – Year 1

Lindsay Wolgel is an professional actor and edu-larp enthusiast. She is currently the middle school drama teacher at a charter school in NYC. Learn about the ways she incorporated larp into her curriculum this past year, via in-class parties, a classroom podcast, creative writing prompts and more!

-

Pandemic Larp Improvisation

Larp organizers have learned a thing or two about organizing scenarios. How have we applied those skills during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

Larp in Leadership Development at the Royal Norwegian Naval Academy (RNNA)

in

Naval cadets became more role flexible as a result of the use of larp in training, and those who were positively inclined gained greater benefits.

-

Solmukohta 2020: 500 Magic Schools for Children and Youth

This panel brings together NGOs, companies and other entities that run magic schools for kids and youth; presenting themselves and their work.

-

Overview of Edu-Larp Conference 2019

Edu-larp can be described as implementing live-action role-playing games in formal or informal educational contexts, “used to impart pre-determined pedagogical or didactic content” (Balzer & Kurz 2015). The aim of the Edu-larp Conference 2019 was to present and discuss recent international research as well as share best practice examples or innovative formats of edu-larp.The first