Category: Theory

-

Performance and Audience in Larp

“When we larp, some of the time we are in a performing role, and some of the time in an audience role. And that is ok! It’s the same in real life, after all. We shouldn’t see this as larp falling short of an aesthetic ideal in which such concepts don’t apply. Larp doesn’t have…

-

The Art-Larp Paradox

“In adapting larp practices to be suitable for artistic spaces and audiences, embodiment, and player agency is susceptible to compromise – potentially sacrificing the artistic essence of larp itself,” says Alex Brown.

-

Together, Apart: Dyadic Play in Larp

in

Designing characters in pairs can lead to two people locked into a singular dynamic that shapes the larp experience around them.

-

The General Problem of Indexicality in Larp Design

in

When things are done “for real” there is always some confusion on how real is real, as there are numerous different levels of simulation, representation, and performance.

-

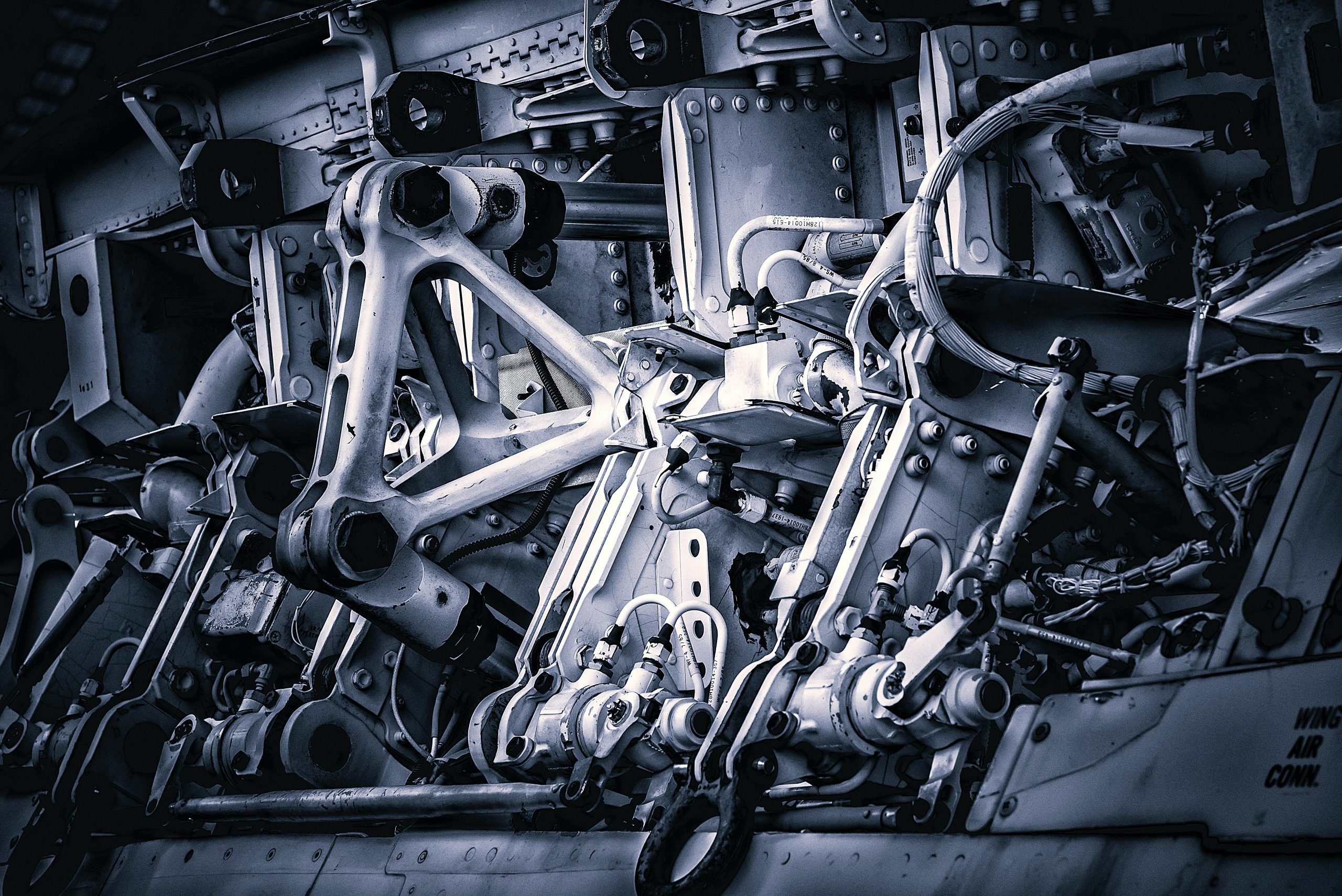

The Interaction Engine

in

The interaction engine is a specific type of larp design where the primary focus is on enhancing playability by ensuring that every action generates new possibilities and emotional impact.

-

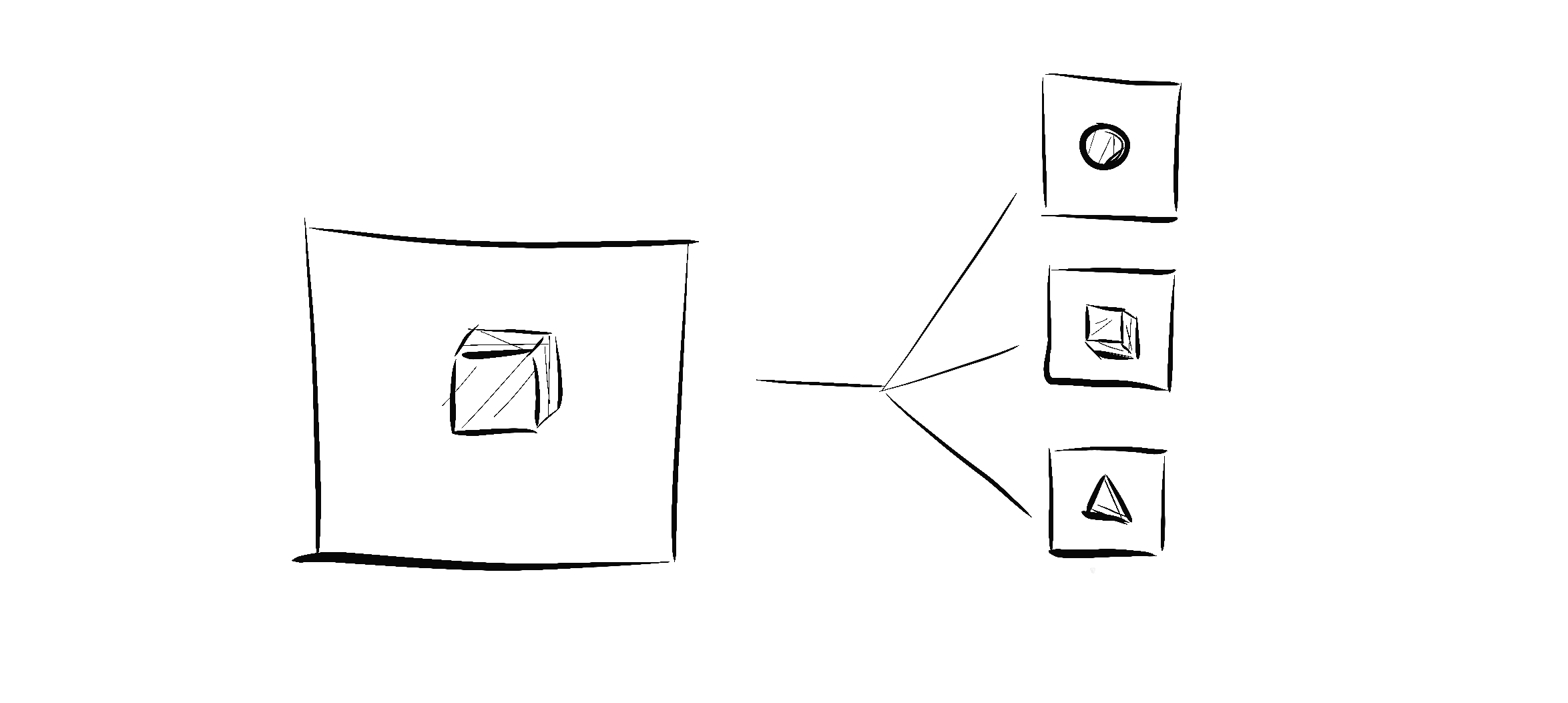

The Descriptor Model

in

How do you successfully communicate about your larp so as to to get the right participants with the right expectations? Here’s a model for classifying and describing larps.

-

Defining Nordic Larp

in

‘Nordic Larp’ has a function. It still signals something to the public. These things might not be unique, or they might have other equivalents within other traditions, but to participants it still says something.

-

Against Design

in

Stop using experience product delivery as the primary factor when evaluating larp projects.

-

Readdressing Larp as Commodity: How Do We Define Value When the Customer Is Always Right?

in

In this article, the author returns to the topic of larp as a commodity, taking a look at it in a context that is defined by numerous crises.