Tag: Knutepunkt

-

Character-based Design and Narrative Tools in the French Style Romanesque Larp

This text aims to present the romanesque style larp in relation to other similar larp styles in Europe & establish some tools that are use to create them.

-

YouTube and Larp

Mo Mo O’brien shares how she accidentally became a YouTube celebrity and offers some tips on how you can successfully create videos about larp.

-

Playing the Stories of Others

in

Larps that treat social issues often aim to create empathy for real people who live in circumstances different from ours by putting us in their shoes.

-

Food for Thought: Narrative Through Food at Larps

in

Food is an essential part of culture. Taste and smell may be more abstract senses but they have the power to bring strong experiences, no less so in larp.

-

History, Herstory and Theirstory: Representation of Gender and Class in Larps with a Historical Setting

in

History can be an amazing source of settings for larp! Here are some ways to make sure you’re doing justice to the underprivileged of the past and of today.

-

Moment-based Story Design

in

Most larp war stories have been provoked by moments of intense experience, of intense emotion. How can we design larps to create these moments?

-

Once Upon a Nordic Larp… – The Knutepunkt 2017 Book

The official book for Knutepunkt 2017 is called Once Upon a Nordic Larp… Twenty Years of Playing Stories and it’s out now!

-

Knutepunkt 2017 – Call for Papers

in

Knutepunkt 2017 Call for Papers. The next Knutepunkt conference will be held in Norway and now the organizers are asking for papers for next years books.

-

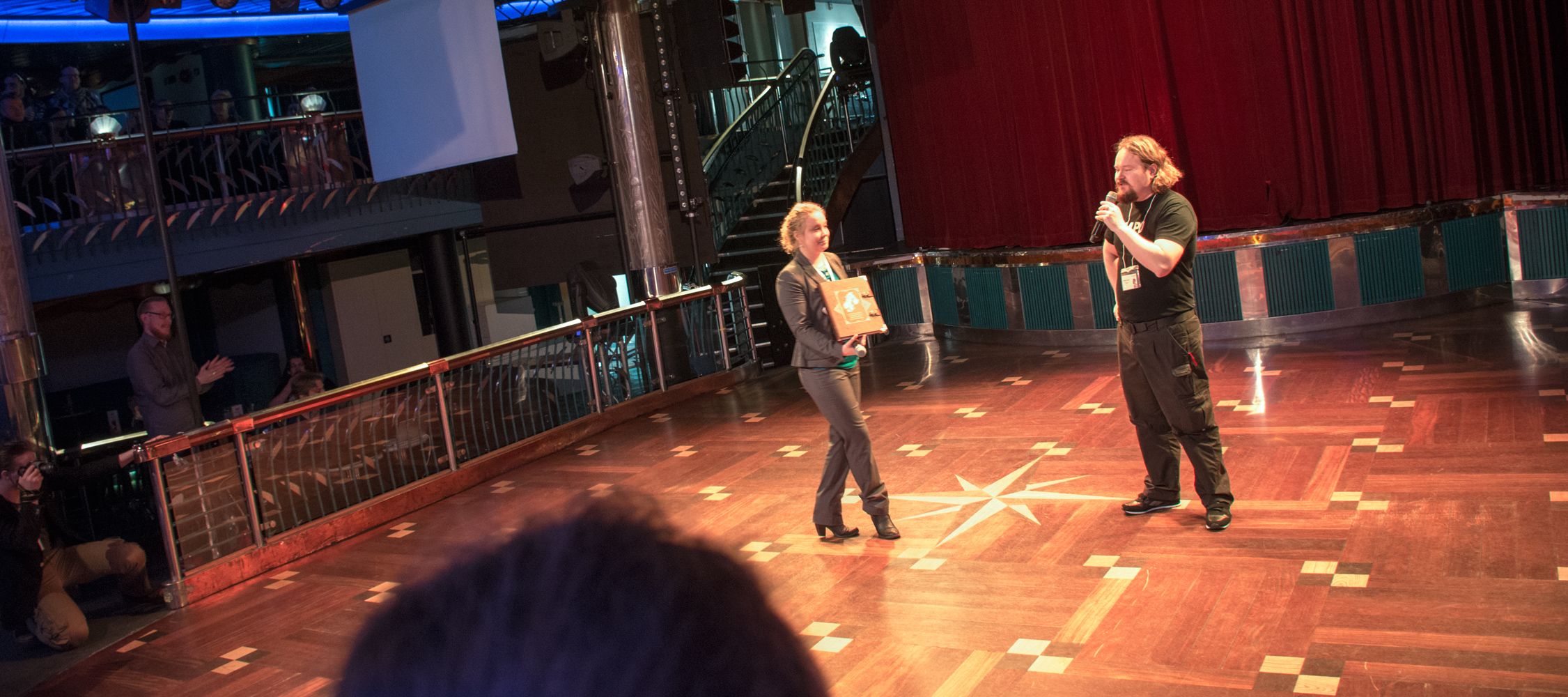

Solmukohta 2016 – Summary

The Finnish edition of the Nordic larp conference Knutepunkt, Solmukohta 2016, is now over. This post will be continuously updated with links to articles, reports, photo albums, videos, slides, books and other relevant documentation.

-

Ship Ahoy! Mark your calendar for Solmukohta 2016!

in

On Wednesday the 9th to Monday the 14th of March 2016 it’s once again time for the international roleplaying conference Solmukohta. The conference often known as Knutepunkt is this year in Finland and therefore goes by it’s Finnish name Solmukohta for 2016. This Solmukohta will be truly Baltic as the location is a Tallink Silja cruise