Tag: Featured

-

Immersion through Diegetic Writing in Character

in

Examples, case studies, and testimonies from larpers about in-game writing.

-

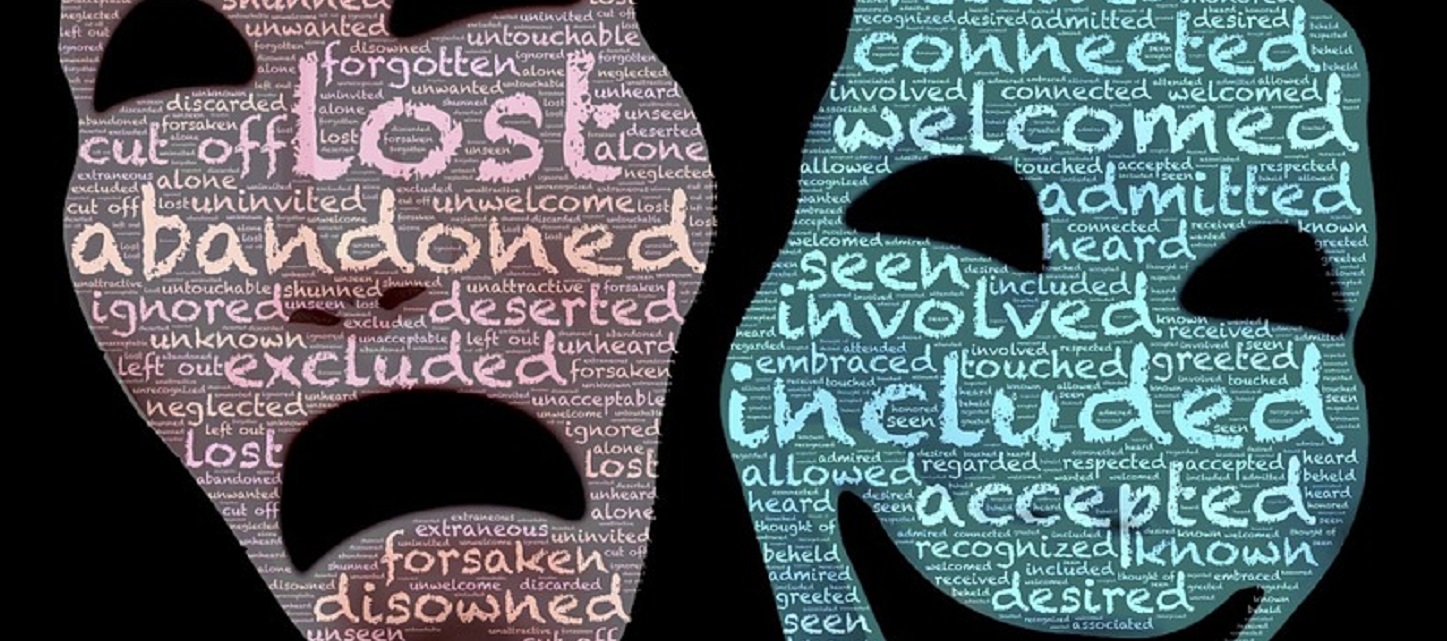

We Share This Body: Tools to Fight Appearance-Based Prejudice at Larps

in

How fatphobia, ageism, and rejection based on perceived attractiveness can influence play and negatively impact larpers.

-

Three Forms of LAOGs

in

This article presents a categorization of LAOGs – depending on how they make use of the communication channels in place. It identifies three different forms: The Diegetic Call, The Invisible Call, and The Metaphorical Call.

-

A Ramble in Five Scenes

in

How age, life experience, and the knowledge you have achieved become part of your larp.

-

Playing with Eros: Consent, Calibration and Safety for Erotic & Sex Roleplay

in

Erotic games are meant to be played by consenting adults who approach sexual play with openness, honesty, and clarity. The tools and principles outlined here will help you prepare for, play, and debrief from erotic games so everyone involved has a safe, consensual, pleasurable, and fun experience.