Tag: Larp Design

-

Emotionally Pacing for Larps – How To Get the Best Rollercoaster Ride

“Pace yourself and pace your design. Intense emotional experiences become more available to you and more sustainable if you have variety to the intensity of your play, both as a designer and as an individual player.”

-

River Rafting Design

in

River Rafting design can help create a more engaging and dynamic player experience from the very beginning of a larp, with a higher chance of many moments of emotional impact, instead of very few towards the end.

-

Design for young adult players: The relevance of designing for hope, agency and inclusion

in

How can larp designers include young adults as co-creators and peers in the design and play processes?

-

The Emotional Core

in

Sometimes in larps I get bored and disconnected. The solution? I need to start by looking for something to care about.

-

Dinner Warfare

in

Creating subtle but strong emotional pressure based on specific relations when designing eating situations in larps.

-

Good Cakes, Bad Cakes: Character and Contact Design as a Factor of Personal Game Experience

in

Compared to free player-driven contact creation, contact design by the organisers is a stronger promise to me and other players struggling with uncertainty on whether we too will be relevant and included.

-

Building Player Chemistry

in

This article By Nór Hernø, introduces a workshop tool to help build player chemistry before a larp.

-

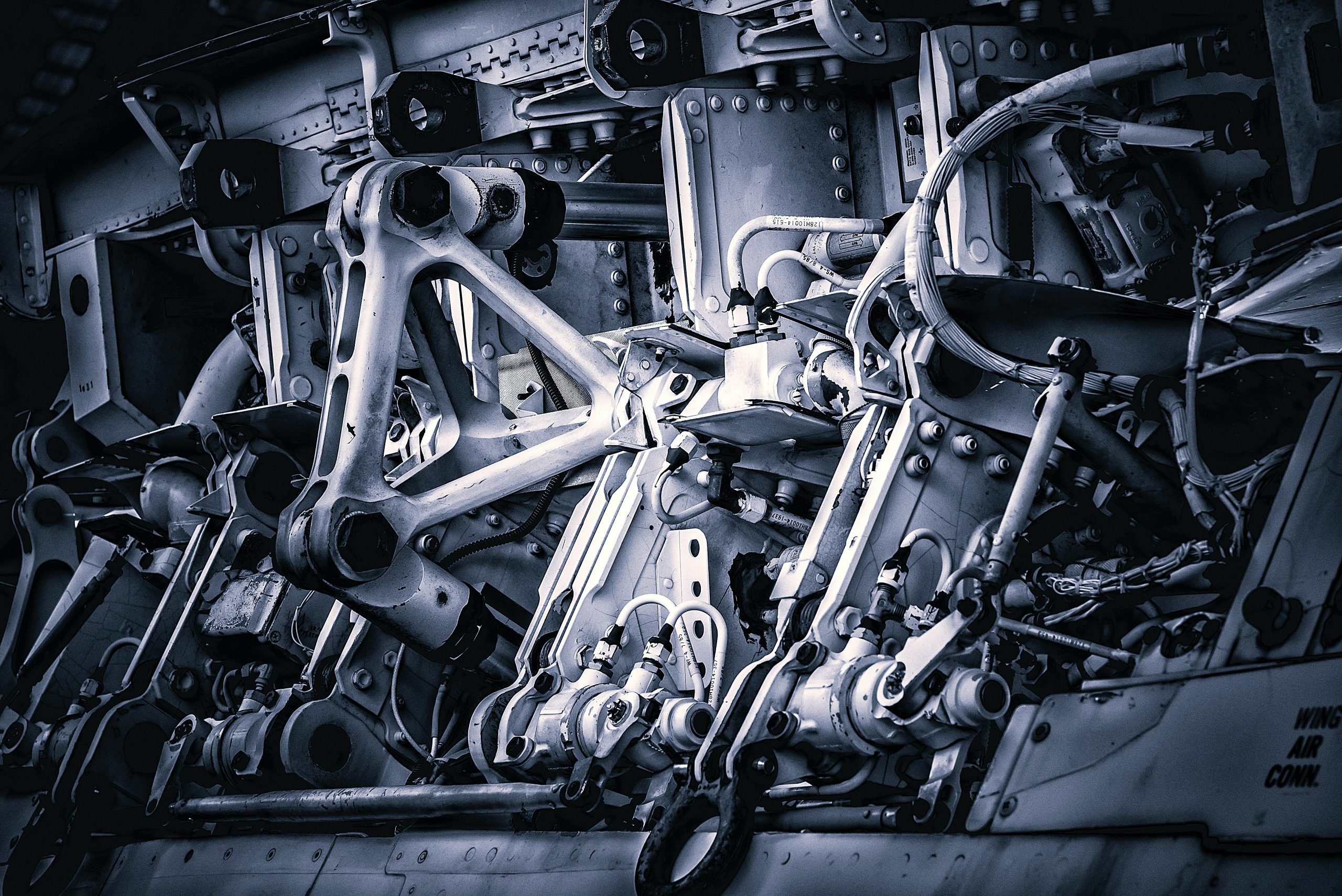

Odysseus: In Search of a Clockwork Larp

Running a clockwork larp is a fool’s errand, because the very point of a clockwork is interdependence, and the very point of a larp is agency. The Odysseus team invested a massive amount of skilled labour to take this paradox head-on.

-

The Interaction Engine

in

The interaction engine is a specific type of larp design where the primary focus is on enhancing playability by ensuring that every action generates new possibilities and emotional impact.

-

For Design

in

A response to the recent article ‘Against Design’ by Widing & Nordwall, arguing for the essentialness of design in larp practice.