Tag: Knutepunkt-books

-

Beyond the Funny Hat

When larping, players don’t always wear costumes, and even when costumed, a character ought to be more than a funny hat. Here, we offer practical ways to flesh out how a character moves and speaks, in the hope of making it easier for you to do so.

-

Artificial Affluenzas

Playing a super-rich character in a larp probably sounds fun and easy. It is neither, at least not at all times. Centrally, it requires a fine line of balancing, in order to not take the role over the top, but sufficiently close, in order to provide the most optimal playable content to other participants.

-

Knutepunkt 2021 Call for Papers

in

Knudepunkt 2021 has issued a call for papers! Pitches are due 10 July 2020 and the theme of the conference, and book, is “Where the magic happens”.

-

Larp and Prejudice: Expressing, Erasing, Exploring, and the Fun Tax

in

Designers of larps with a real-world setting face questions about how to deal with prejudice. This article looks at three possible approaches.

-

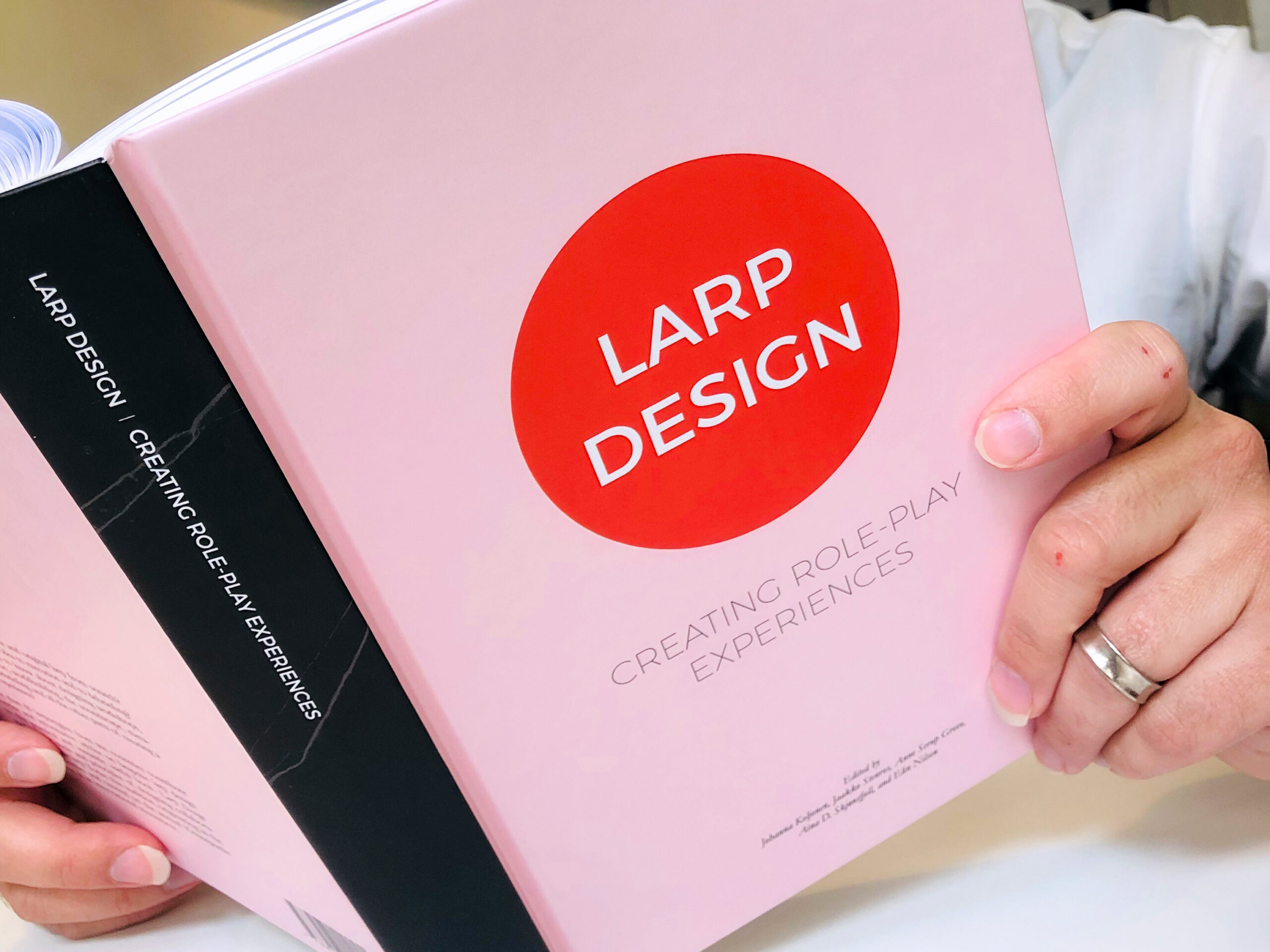

Review of Larp Design: Creating Role-Play Experiences

in

The gorgeous and impressive Larp Design book is a collection of practical and useful essays for beginners as well as experienced designers.

-

Larp Design Glossary

in

The original version of this glossary was published in the 2019 book Larp Design: Creating Role-Play Experiences. 360° illusion Larp design idea where what you see is what you get. The environment is perceived as authentic, everything works as it should affording participants to engage in authentic activity for real, and participants perform immersive role-play.

-

High Resolution Larp Revisited

in

Revisiting Andie Nordgren’s 2008 article on High Resolution Larping.

-

Tensions between Transmedia Fandom and Live-Action Role-Play

in

Larping in a franchise means players are familiar with the material. Yet fan practice may contradict larp’s flexibility. How to address these tensions?

-

Knutpunkt 2018 Companion – Call for Content

We want your content for the Knutpunkt 2018 Companion! This year the publication will be online and accept many different types of content. Contribute here!

-

Three Roads (of Translation) Not Taken: Different Degrees of Openness of the Work (and of the Game)

in

Abstract From the Julio Plaza’s proposition that, based on the concept of open work of Umberto Eco, categorises the relationship author-work-reception in three degrees, and the division in cultural events in reception, interaction and participation, seen in the research of Kristoffer Haggren, Elge Larsson, Leo Nordwall and Gabriel Widing, this study plans to compare three