Tag: Featured

-

The General Problem of Indexicality in Larp Design

in

When things are done “for real” there is always some confusion on how real is real, as there are numerous different levels of simulation, representation, and performance.

-

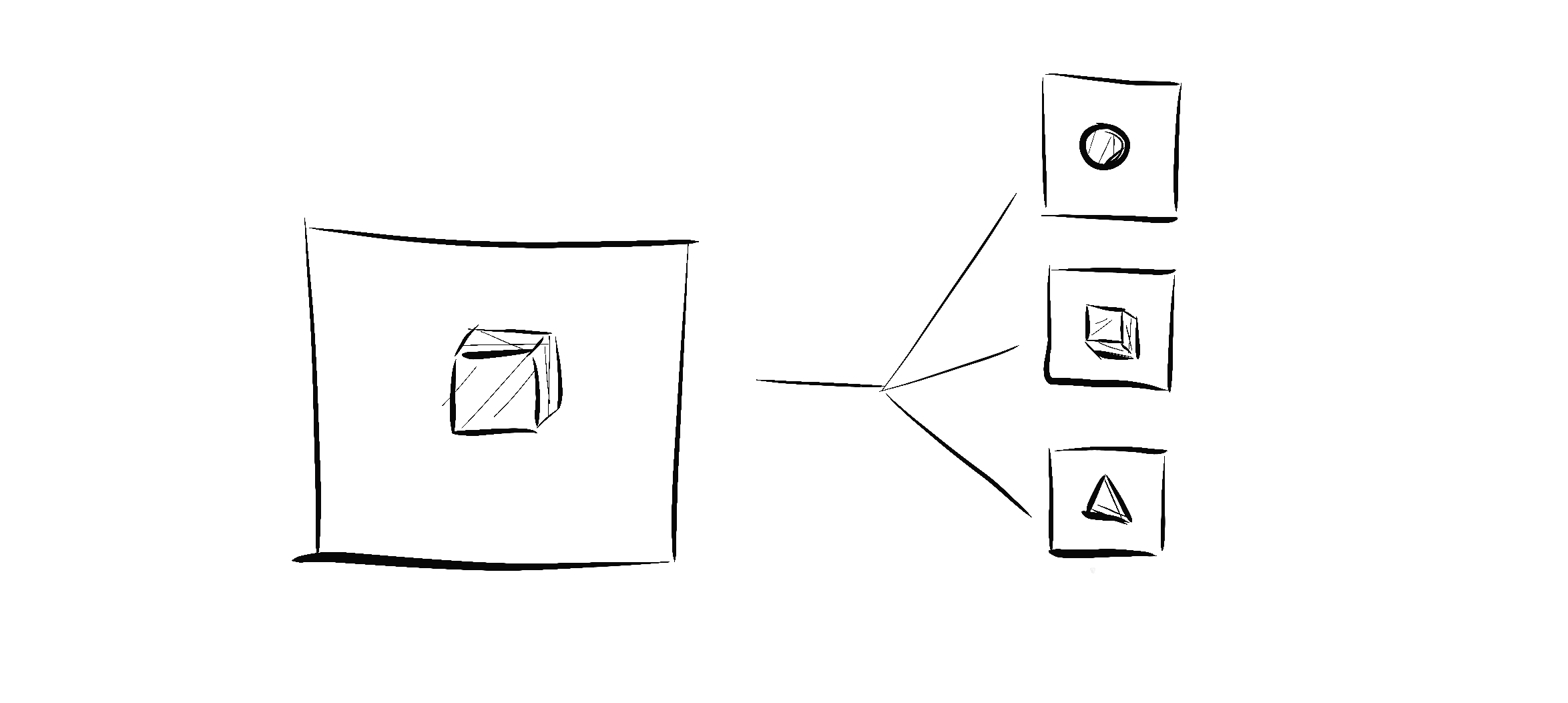

The Interaction Engine

in

The interaction engine is a specific type of larp design where the primary focus is on enhancing playability by ensuring that every action generates new possibilities and emotional impact.

-

For Design

in

A response to the recent article ‘Against Design’ by Widing & Nordwall, arguing for the essentialness of design in larp practice.

-

The Descriptor Model

in

How do you successfully communicate about your larp so as to to get the right participants with the right expectations? Here’s a model for classifying and describing larps.

-

Defining Nordic Larp

in

‘Nordic Larp’ has a function. It still signals something to the public. These things might not be unique, or they might have other equivalents within other traditions, but to participants it still says something.

-

Rules, Trust, and Care: the Nordic Larper’s Risk Management Toolkit

in

This article discusses how to come to terms with the fact that risks at larps cannot be eliminated, and how to manage them instead.

-

Remember That Time… We Tried to Film a Larp

In this article, Sophia Seymour and Martine Svanevik discuss their experiences of filming a larp for a documentary.

-

Against Design

in

Stop using experience product delivery as the primary factor when evaluating larp projects.

-

Did We Wake?

Reflections on Before We Wake, a larp played in 2015, a larp which refused to let go, which insisted on being untangled…, and utterly unlike any other larp ever played.