Tag: Featured

-

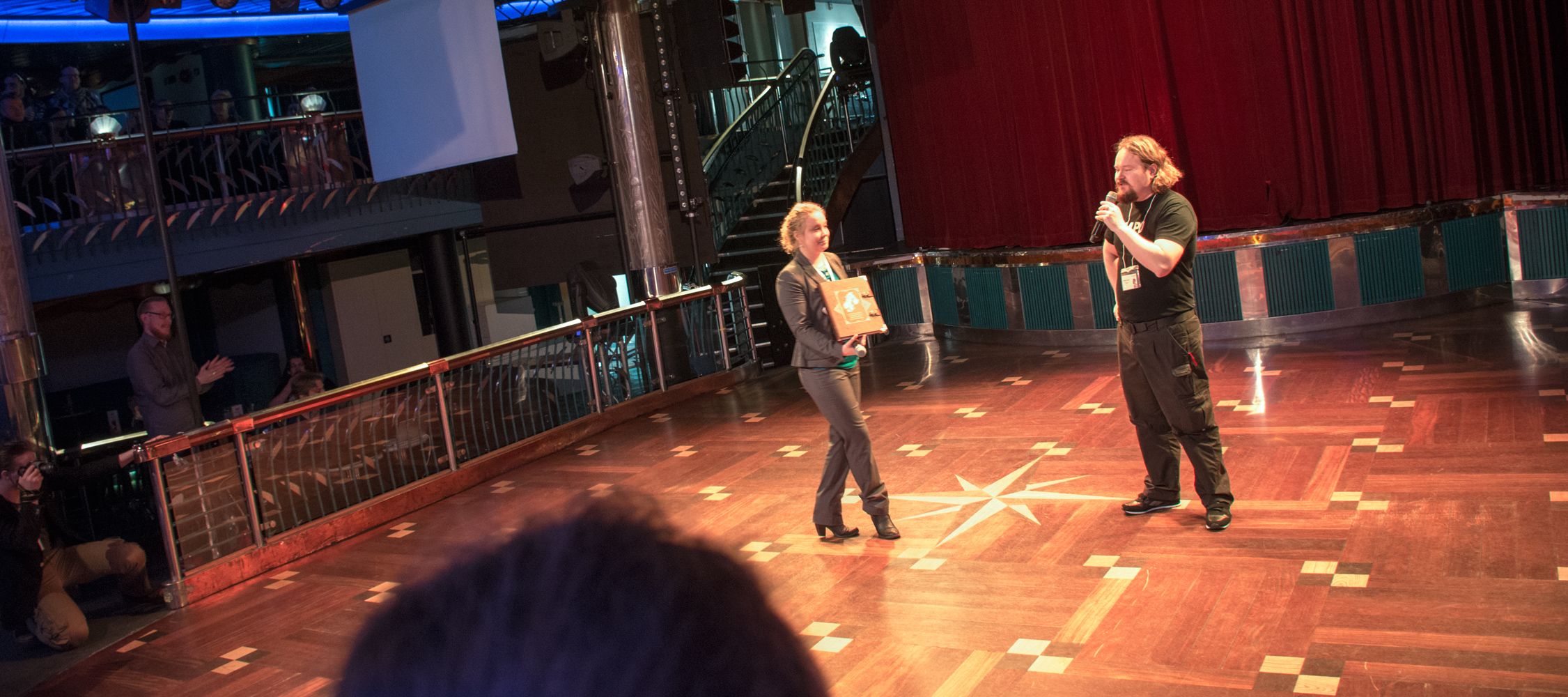

Solmukohta 2016 – Summary

The Finnish edition of the Nordic larp conference Knutepunkt, Solmukohta 2016, is now over. This post will be continuously updated with links to articles, reports, photo albums, videos, slides, books and other relevant documentation.

-

Nordic Larp Talks Helsinki 2016

in

Nordic Larp Talks is a series of short, entertaining, thought-provoking and mind-boggling lectures about projects and ideas from the tradition of Nordic Larp. This year Nordic Larp Talks will be hosted in Helsinki, Tuesday March 8th at 19:00 and you are of course more than welcome to join us! The event will be held at Aalto University School

-

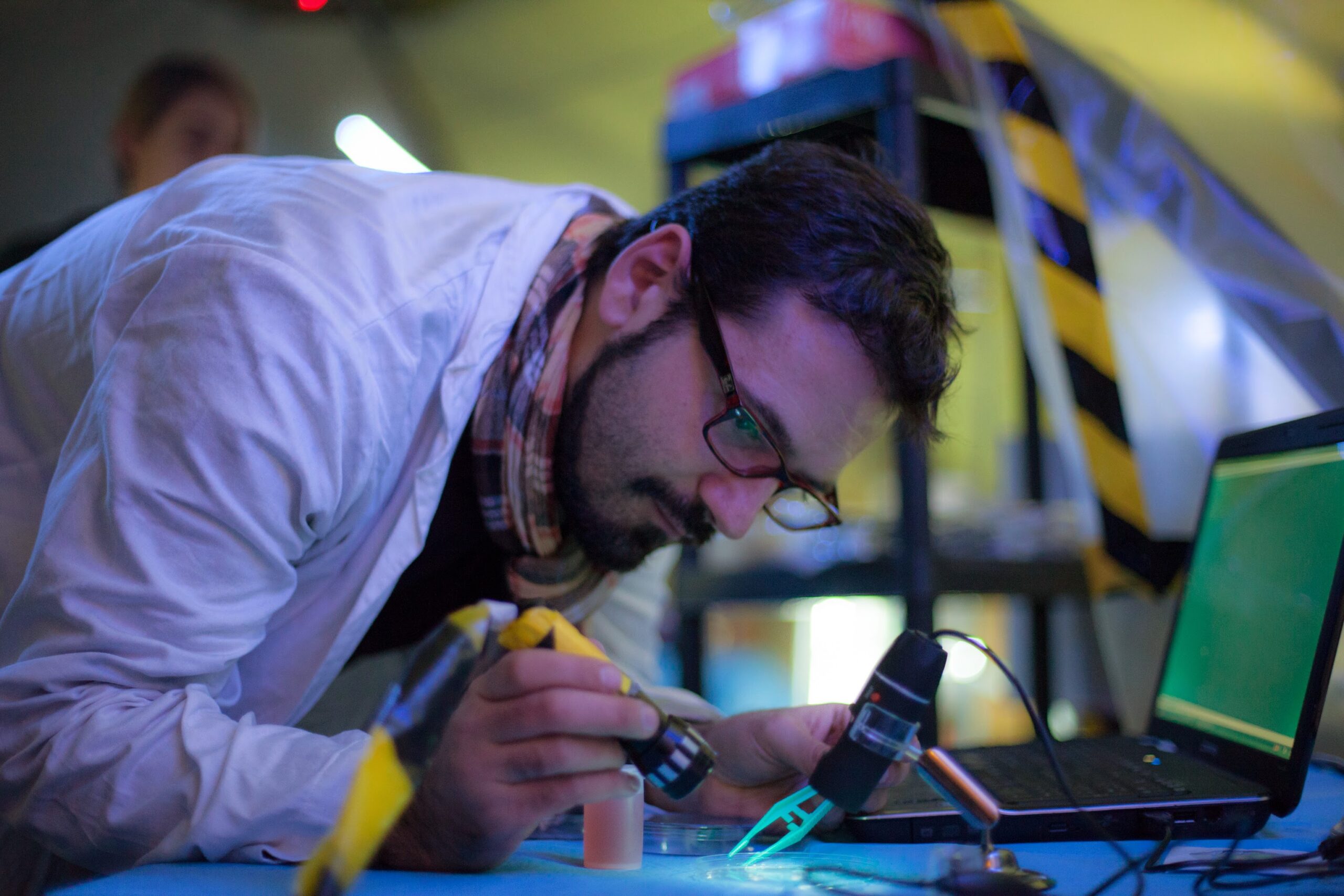

The Whole Is Greater than the Sum of Its Parts – Voices from Black Friday

In this larp we didn’t have restrictions. We just wanted to organize the coolest larp ever played in Italy. At least, that’s what I wanted.Chiara Tirabasso, Black Friday larpwright Chiara Tirabasso is one of the many larpwrights behind Black Friday. She perfectly sums up two elements of the organizing team: a great ambition on quality

-

Fairweather Manor: Perspectives from a United States Player

I thought I’d write up a game summary about my experience playing Fairweather Manor, as there seems to be some interest. My background is as an American larper with some-to-moderate larp experience in the American scene, whose first international larp was College of Wizardry earlier this year. Fairweather Manor was set in early 1914, and

-

Legion – Trans-Siberian Railroading

Legion, or Legie as it is called in its original language, is a Czech larp that had already had six runs by the time the international run was played, and is a game for 54 pre-written characters, both soldiers and civilians. The story is based on (very well researched) historical accounts of the Czech Legion…

-

Fairweather Manor – The Latest Iteration of the Blockbuster Formula?

Fairweather Manor is a historically-inspired international larp for 140 whose first run took place in Zamek Moszna, Poland, on the 5-8th of November 2015. It was created by the Liveform/Rollespilsfabrikken team already behind the creation of College of Wizardry. As such, the format, creative team, and overall design of the larp connects Fairweather Manor to…

-

I Will Never Larp Again

in

You feel like there’s an invisible wall between you and everyone else. The others are laughing, joking and talking enthusiastically. But you’re not. Couldn’t things just have been different? After all that you invested, nothing has been returned to you; empty heart, empty wallet and lots of time that could have been better spent.

-

Starting a Russian Revolution

A visit to Russian “Larp-poem 1905” to do living history and dream of changing the past Have you heard about the Russian revolution of 1905? Don’t be embarrassed if you haven’t, it’s not that well known, not even Russians talk much about it. Yet, it was an interesting and decisive time in Russian history and,

-

A Refreshing Take on Larp in Film: Review of Treasure Trapped

in

Treasure Trapped (2014), directed by Alex Taylor, is a documentary about larp made by the UK company Cosmic Joke. In a short article in the Wyrd Con Companion Book 2012, the filmmakers describe the background of the film’s journey. The movie started as an exploration of modern day fantasy larp in the UK and its

-

Love, Sex, Death, and Liminality: Ritual in Just a Little Lovin’

in

Just a Little Lovin’ is commonly touted as one of the best Nordic larps ever designed by those who have played it. Originally written in 2011 by Tor Kjetil Edland and Hanne Grasmo, the larp explores the lives of people in alternative sexual and spiritual subcultures during the span of 1982-1984 in New York who…