Tag: Poland

-

Playing First Contact in Eclipse, a Spectacular 3-day Sci-Fi Larp

The larp Eclipse “was like a simulated near-death experience, an attempt to convince players they were on the brink of unimaginable transformation,” reflects Adrian Hon, in this detailed and thoughtful article: spoiler warning!

-

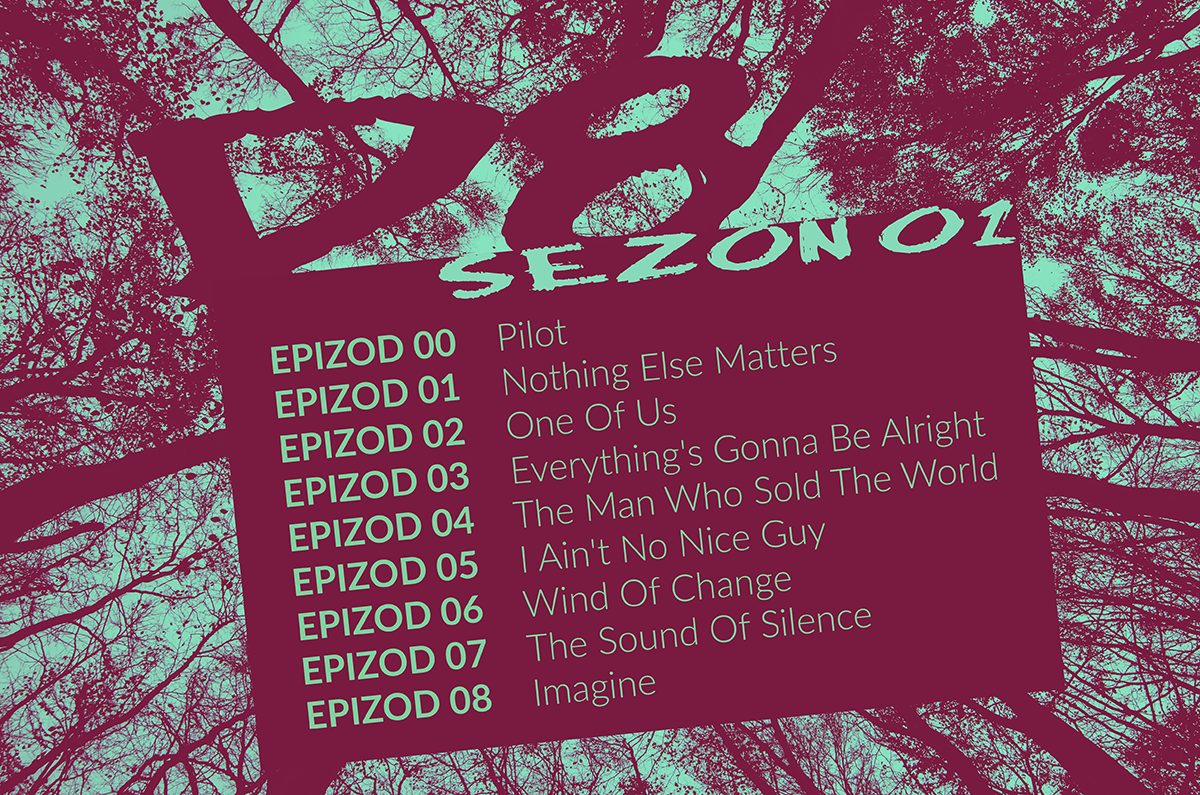

D8 – Fascinating Paradox

When I heard some first mentions about the idea behind D8, I felt it’s going to be a really interesting thing. Knowing them personally, I occasionally drifted in each conversation towards this larp, to learn more. A design document for this larp got to me in a phase of small fixes and editing. It evoked

-

Keeping Volunteers Alive

in

Organising larps is a multi-disciplinary exercis. A large part of my larp work consists of managing large (25+) teams of people, most of them volunteers.

-

White Wolf’s Convention of Thorns – A Blockbuster Nordic Larp

Convention of Thorns is an official White Wolf Nordic-style Vampire: the Masquerade larp. The first run was held between October 27-30, 2016 at Zamek Książ, a castle in Poland. The larp was a joint collaboration between White Wolf and Dziobak Larp Studios. This scenario plays out a crucial moment in the canon of vampiric history,

-

The Book of Polish Larp

A new Polish book about larp is out, this is what the authors has to say about it: From the intense 5-players chamber larp to the post-apocalyptic week-long larp festival for almost 600 people. Polish larp scene is diverse and is rapidly evolving. In the first documentation book about polish larp scene you will have

-

Fairweather Manor: Perspectives from a United States Player

I thought I’d write up a game summary about my experience playing Fairweather Manor, as there seems to be some interest. My background is as an American larper with some-to-moderate larp experience in the American scene, whose first international larp was College of Wizardry earlier this year. Fairweather Manor was set in early 1914, and

-

Fairweather Manor – The Latest Iteration of the Blockbuster Formula?

Fairweather Manor is a historically-inspired international larp for 140 whose first run took place in Zamek Moszna, Poland, on the 5-8th of November 2015. It was created by the Liveform/Rollespilsfabrikken team already behind the creation of College of Wizardry. As such, the format, creative team, and overall design of the larp connects Fairweather Manor to…

-

College of Wizardry 2014 Round-up

College of Wizardry is a Harry Potter themed larp made by the organizations Rollespilsfabrikken (Denmark) and Liveform (Poland). You can read more about the individual team members at the College of Wizardry Team page. The larp is set in the beautiful Polish Czocha Castle and the first run was helt in November 2014 with follow-ups planned for April

-

Video Report from The Game, a Polish Larp Inspired by The Hunger Games

A very interesting video report from a Polish larp inspired by The Hunger Games. It’s in polish but with full English subtitles.

-

KOLA 2013 Larp Conference Publication

Polish larp has reached a milestone: Very first international publication from this years KOLA conference now in english! Please take a moment to browse through it, as it is a big step for polish larp and a huge effort on their part to make their scene available to the international larpers. You can find the