Tag: Online larp

-

Actual Plays of Live-Action Online Games (LAOGs)

Why make recordings of larps played online? Read about the reasons for doing so, the history of the activity, and the considerations involved.

-

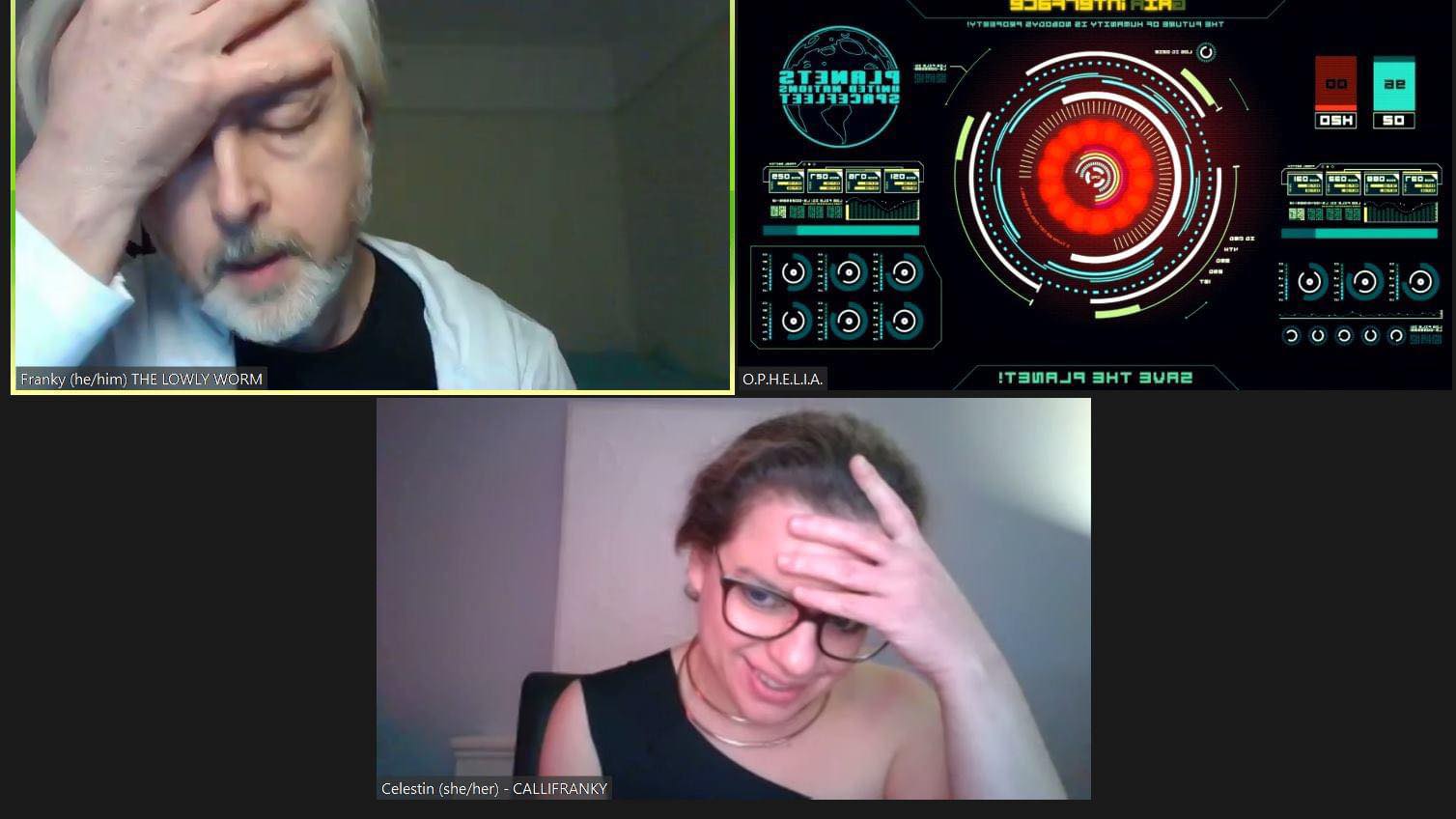

Listen 2 Your Heart Season 8: An Unexpectedly Bleedy Experiment

Reflections on an online larp adaptation of the popular Netflix dating series Love is Blind.

-

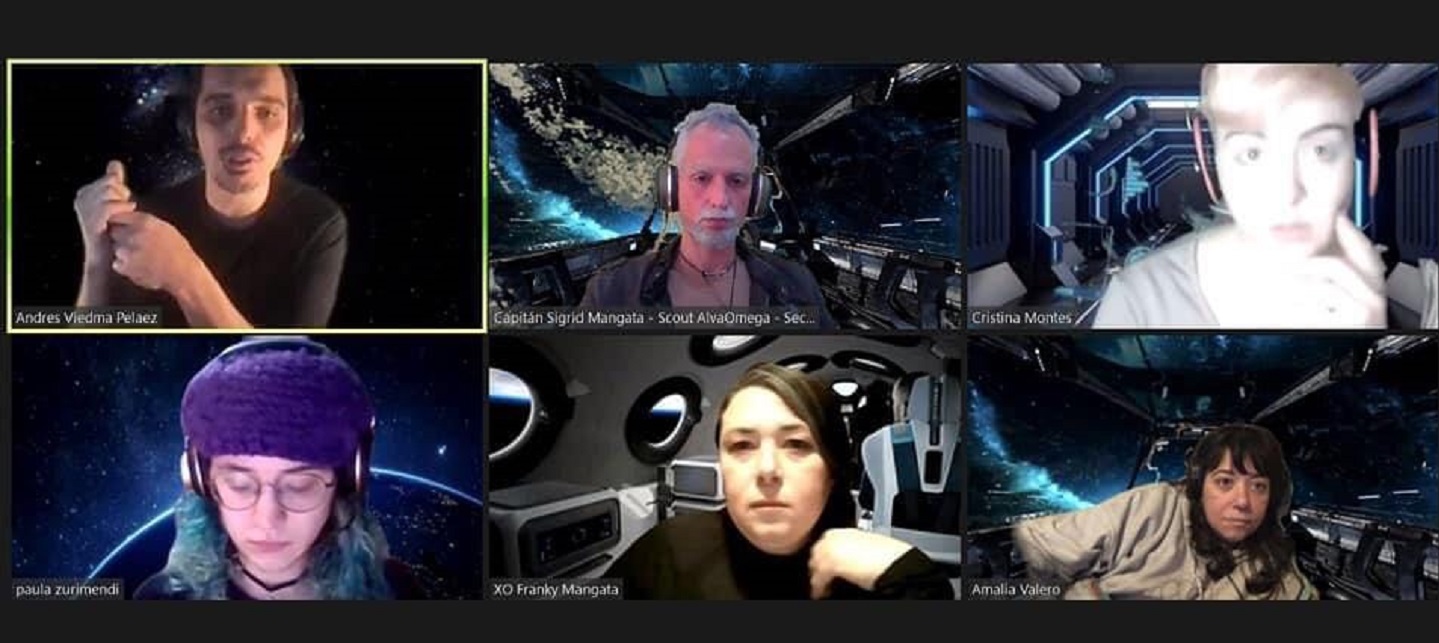

The Online Larp Road Trip

The pandemic was catastrophic for physical larp but also acted as the catalyst for the development of online larp.

-

Pandemic Larp Improvisation

Larp organizers have learned a thing or two about organizing scenarios. How have we applied those skills during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

The Magic of the Silicon Screen

in

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, mainstream larp has ventured into the magic of modern technology and what it has to offer.

-

Immersion through Diegetic Writing in Character

in

Examples, case studies, and testimonies from larpers about in-game writing.

-

Three Forms of LAOGs

in

This article presents a categorization of LAOGs – depending on how they make use of the communication channels in place. It identifies three different forms: The Diegetic Call, The Invisible Call, and The Metaphorical Call.

-

I Stepped into the Eternal Circle, Animus: the Larp

Experiences of play and facilitation in the online larp Animus: The Eternal Circle by Chaos League.

-

Accessibility in Online Larp

in

Online larps have the potential to make games accessible for a wider variety of players who may be excluded from mainstream, face-to-face larps. Here we outline some accessibility methods.

-

Navigating Online Larp

in

There’s a lot to think about as we adapt how we design and play larps to our current constraints, but with luck the community as a whole can see that as exciting rather than offputting.