Tag: Larp Design

-

Dance Macabre Blueprint

Detailed explanation of the design and organization of the Dance Macabre larp, in which pairs of dancers attempt to overcome problems and fears around the subject of love.

-

Basics of Efficient Larp Production

in

An alternative mode of production to the Infinite Hours of labor often spent in larp organizing and volunteering.

-

Review of Larp Design: Creating Role-Play Experiences

in

The gorgeous and impressive Larp Design book is a collection of practical and useful essays for beginners as well as experienced designers.

-

Writing an Autobiographical Game

in

Designing an experience that explores autobiographical themes through metaphor while also incorporating characters based on real people.

-

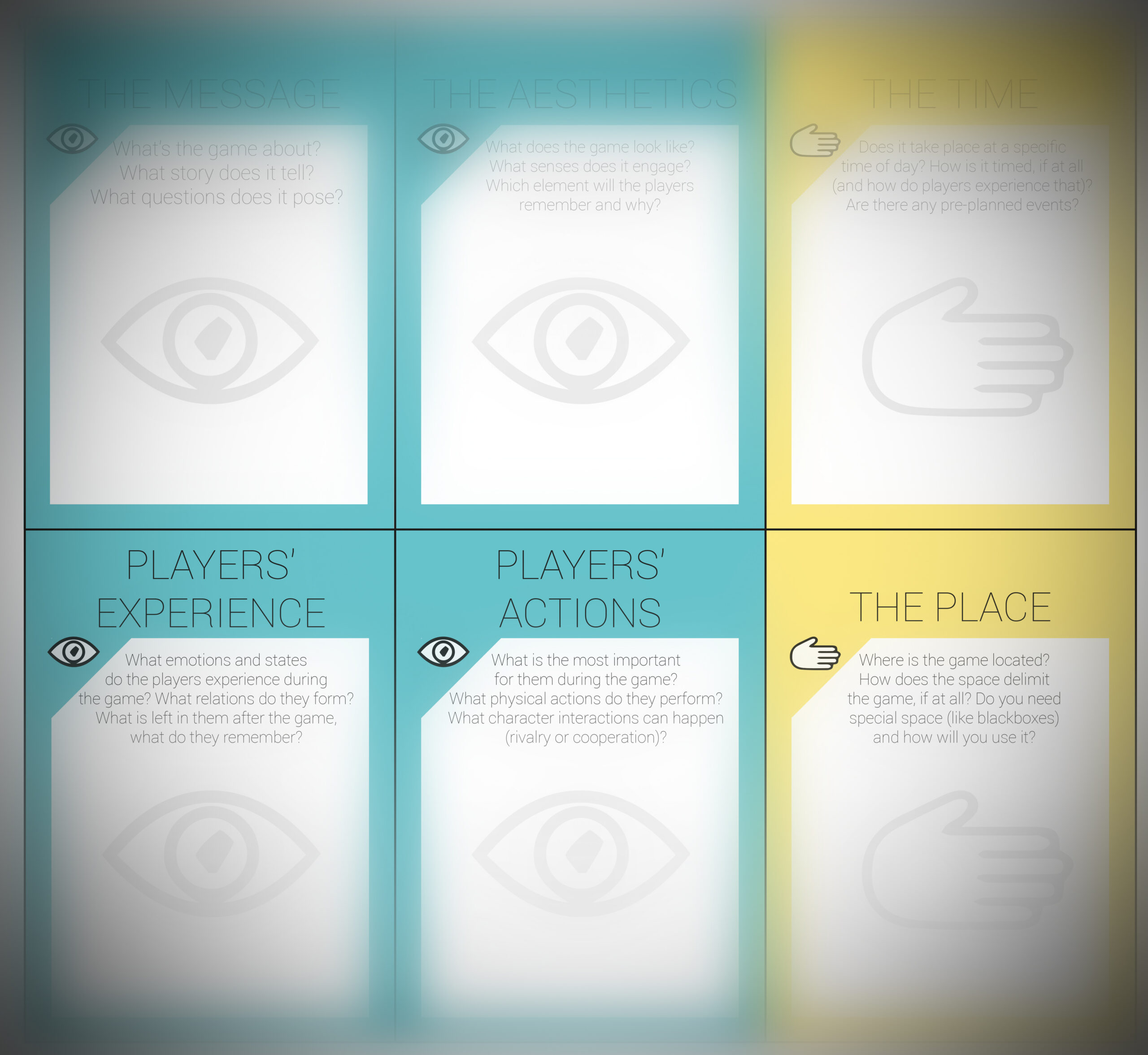

Larp Design Cards

in

Mikołaj Wicher has together with Agnieszka Kisiel (translation) and Marcin Słowikowski (graphic design) produced a set of cards to help with larp design. You can download the cards here.

-

Bad Larp Design: Choking Hazard

in

When someone seems to be choking or having difficulties breathing at a larp, you should always assume the situation is real and go to their immediate aid. Designers should never, ever design larp mechanics that require participants to role-play that their characters have breathing difficulties or are, indeed, choking.

-

The Blockbuster Formula – Brute Force Design in The Monitor Celestra and College of Wizardry

in

2013 and 2014 may be remembered as the conception of the Nordic blockbuster larp. Two ambitious larps – The Monitor Celestra in Sweden and College of Wizardry in Poland – succeeded in attracting an unprecedented level of international attention from media and players. They did so, in part, by advertising their inspiration from established fictional…