Tag: Germany

-

Telling Character Stories

in

There are many ways to tell character stories. Nordic larp design often implies that characters are written by the larpwrights. That’s not always the case.

-

There Is No Nordic Larp – And Yet We All Know What It Means

in

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Nordiclarp.org or any larp community at large. “Nordic larp is like porn. I know it when I see it.”((Adaptation of a quote by United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart (1964) )) Ten years

-

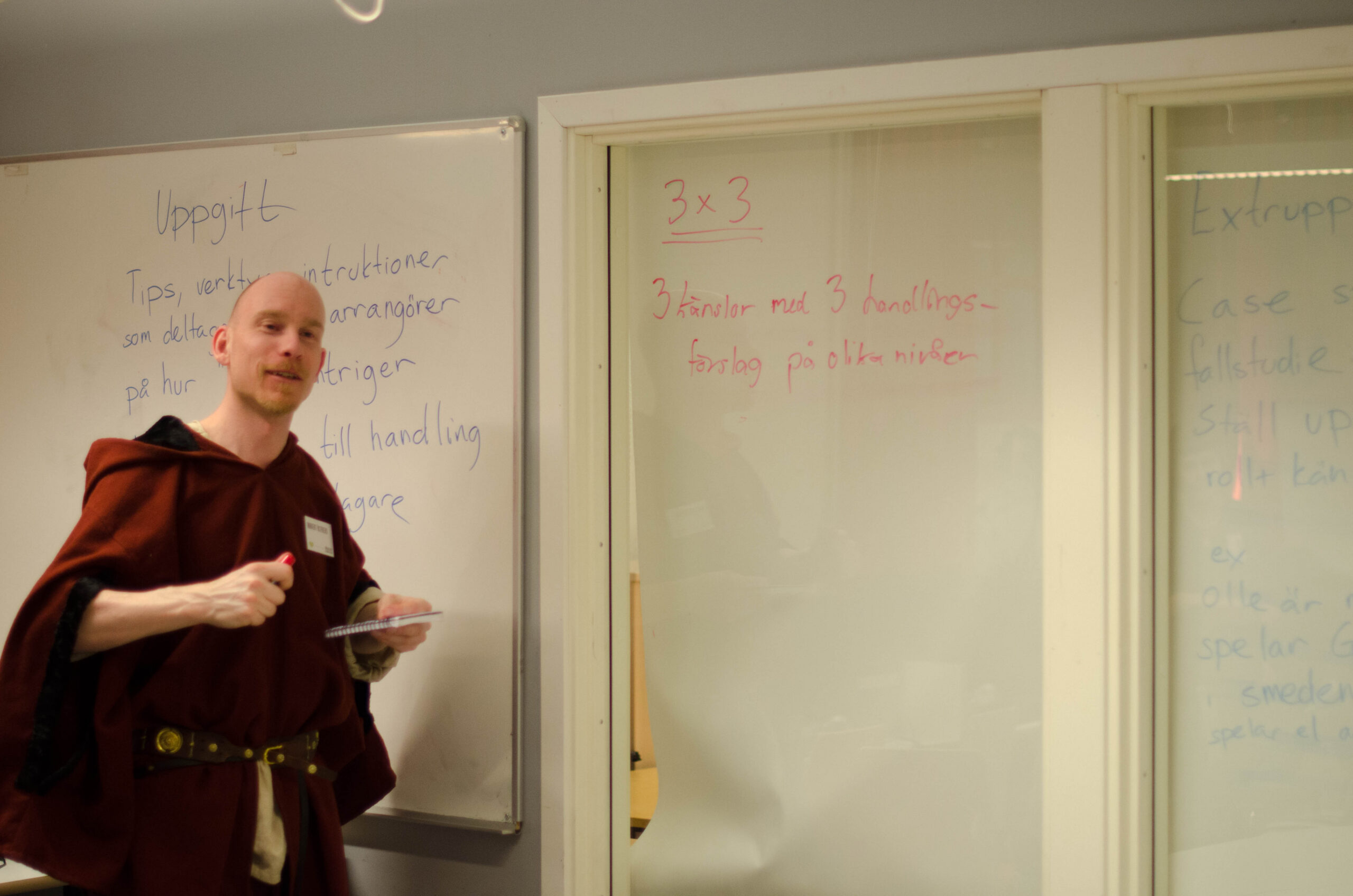

Learning by Playing – Larp As a Teaching Method

in

Tell me, and I will forget.Show me and I may remember.Involve me, and I will understand. Confucius The next generation of teachers will be expected to possess a broad spectrum of competencies and skills. They are faced with a seemingly impossible task: today, classroom instruction should teach not only content but also competence. It should

-

Knutepunkt 2013 Report by Stefan Deutsch

German larper Stefan Deutsch has written a report of his experience at Knutepunkt 2013: http://operation-brainfuck.de/wordpress/?p=110 Discuss and read more about Knutepunkt 2013 in the Nordic Larp Forum: http://nordiclarp.org/forum/viewforum.php?f=6