Tag: Featured

-

Challenging the Popularized Narrative of History

in

The popular version of history will always be tempting for larp designers to draw upon – but it brings a load of cultural baggage and assumptions.

-

Designing Power Dynamics Between Adults and Children in Larps

in

A practice-based approach utilized in edu-larp and leisure larps, including a mythical fantasy campaign.

-

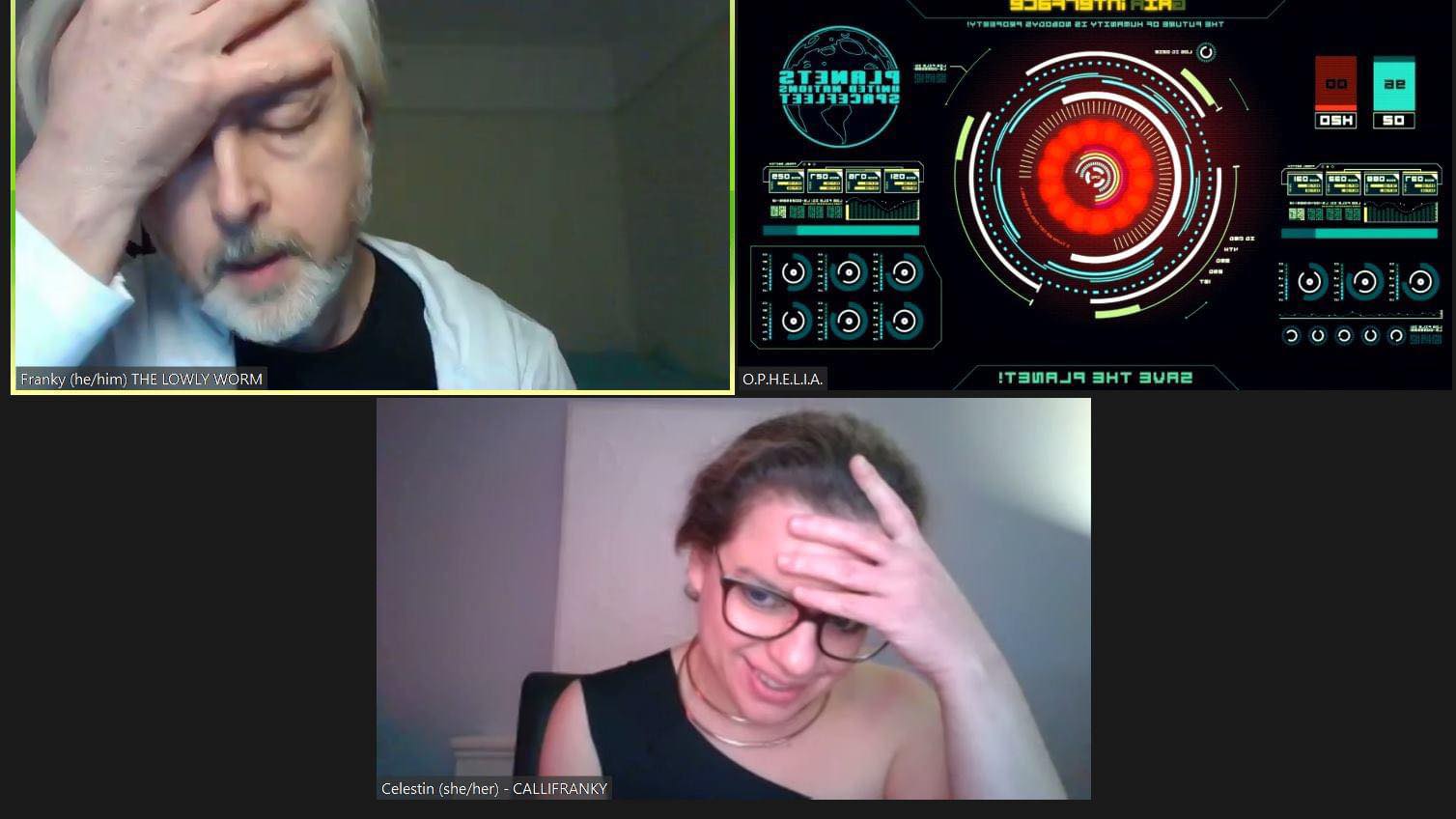

Actual Plays of Live-Action Online Games (LAOGs)

Why make recordings of larps played online? Read about the reasons for doing so, the history of the activity, and the considerations involved.

-

Comments on VR, Larp, Technology, Creation

in

Aesthetics, Possibility and Ethics of an Immersive Mass Media This article is a personal commentary on a few major topics I picked up throughout the past six years of creating for VR/new media and larp. The principal aim of this text is to touch on philosophical themes related to industrial technology, as our community gravitates

-

History is Our Playground – On Playing with People’s Lives

in

How can we treat the lives of people who lived and died centuries ago with respect? How much context should we expect the players to study in order to respectfully portray lives of people in the past? In what detail should we communicate the changes we make for artistic or playability purposes?

-

How I Learned to Stop Faking It and Be Real

in

Communicating about mental health issues can make us better larpers.

-

Extinction Now: Coming to Terms with Dissolution in End(less) Story

We live in an apocalyptic age. The blackbox larp End(less) Story taps into this mortal dread unapologetically and with compassion.

-

A Short Guide to Fix Your Larp Experience

in

Sometimes, when participating in a larp, things just go wrong. But where is the problem? How can you fix it?

-

Possible, Impossible Larp Critique

in

We have not developed similar institutions of critique as exist in the world of passive art. The larp community seems to rely on hearsay, impressions and publicity materials.