Category: Techniques

-

All Quiet on the Safety Front: About the Invisibility of Safety Work

in

Most players and some organizers might not know what the experiences before, during and after a larp are like for safety people.

-

How to Do Night Scenes

in

There is so much potential in night-time scenes. Who wouldn’t love to be dragged from their bed by a monster, or woken by a ghost’s gentle touch? But, they tend to turn anticlimactic. Here’s a solution that can get these scenes to work for you.

-

The Hated Children of Nordic Larp – Why We Need to Improve on Workshops and Debriefs

in

We should design specific exercises that fit the larp and the experience we want to create.

-

Innovations in the Drama Classroom with Larp

in

Larp activities for middle school students born out of a focus on emergence.

-

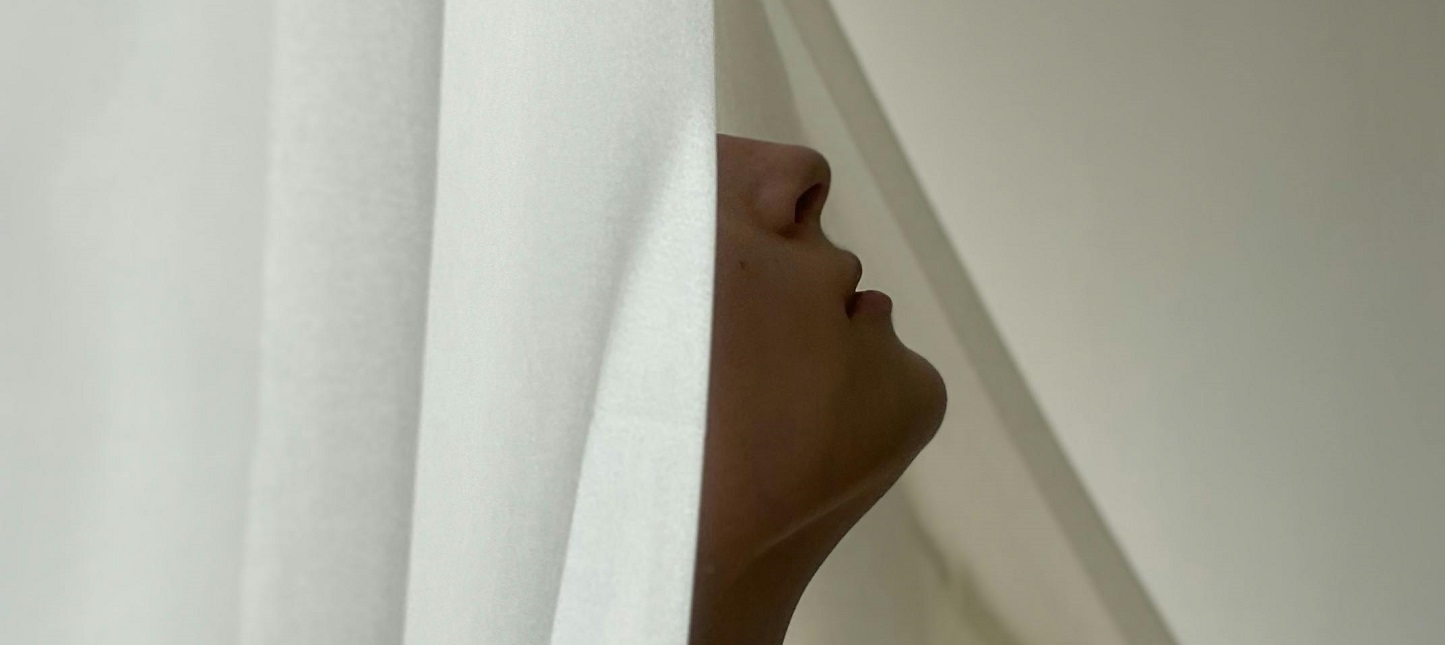

Play Boldly – Let Yourself Be Vulnerable

in

Challenge yourself. Go beyond your comfort zone. Decide to do something you are not sure you can actually pull off. Try something new.

-

Villain Self Care

in

Strategies for playing an antagonist in a larp in rewarding ways, as well as helping with potential negative emotional effects.

-

Designing Power Dynamics Between Adults and Children in Larps

in

A practice-based approach utilized in edu-larp and leisure larps, including a mythical fantasy campaign.

-

How I Learned to Stop Faking It and Be Real

in

Communicating about mental health issues can make us better larpers.

-

An Introvert’s Guide to Playing High Status Characters

in

How to play big commanding character types – my collection of tips and tricks that I have accrued over 20+ years of larping.

-

Participatory Ritual Vocalization

in

How to use vocalization to create a sense of shared ritual in larps?