Category: Knutpunkt 2018

Articles written as companion pieces to the larp conference Knutpunkt 2018.

The following tracks are represented in the articles:

Hearts – Designer and organiser reflections

Diamonds – Tools, tips and tricks for larp designers and organizers

Clubs – Tools, tips and tricks for players

Spades – Larp analysis, discussion and reflection

Joker – Discussions and reflections on the larp community

-

Larp as Life

in

Some hints and tips for larpers who have decided to go pro and make their living from larp.

-

Immerton

in

Immerton is a 4-day larp written by women for women participants, taking place in a fictional society of women in a polytheistic goddess pantheon. Produced by Learn Larp, the game used a feminist sandbox design that emphasized rituals, relationships, collaborative roleplay, and transformational experiences using a meta room, mask play, and multimedia storytelling as core…

-

More Than a Seat at the Feasting Table

in

As Larp as a medium of experience design and performance begins to take traction globally as a source of entertainment, increasingly larp communities are facing a problem that cannot be swept aside any longer: there is a distinct lack of inclusion of people of color in all levels of larp. In order to include people…

-

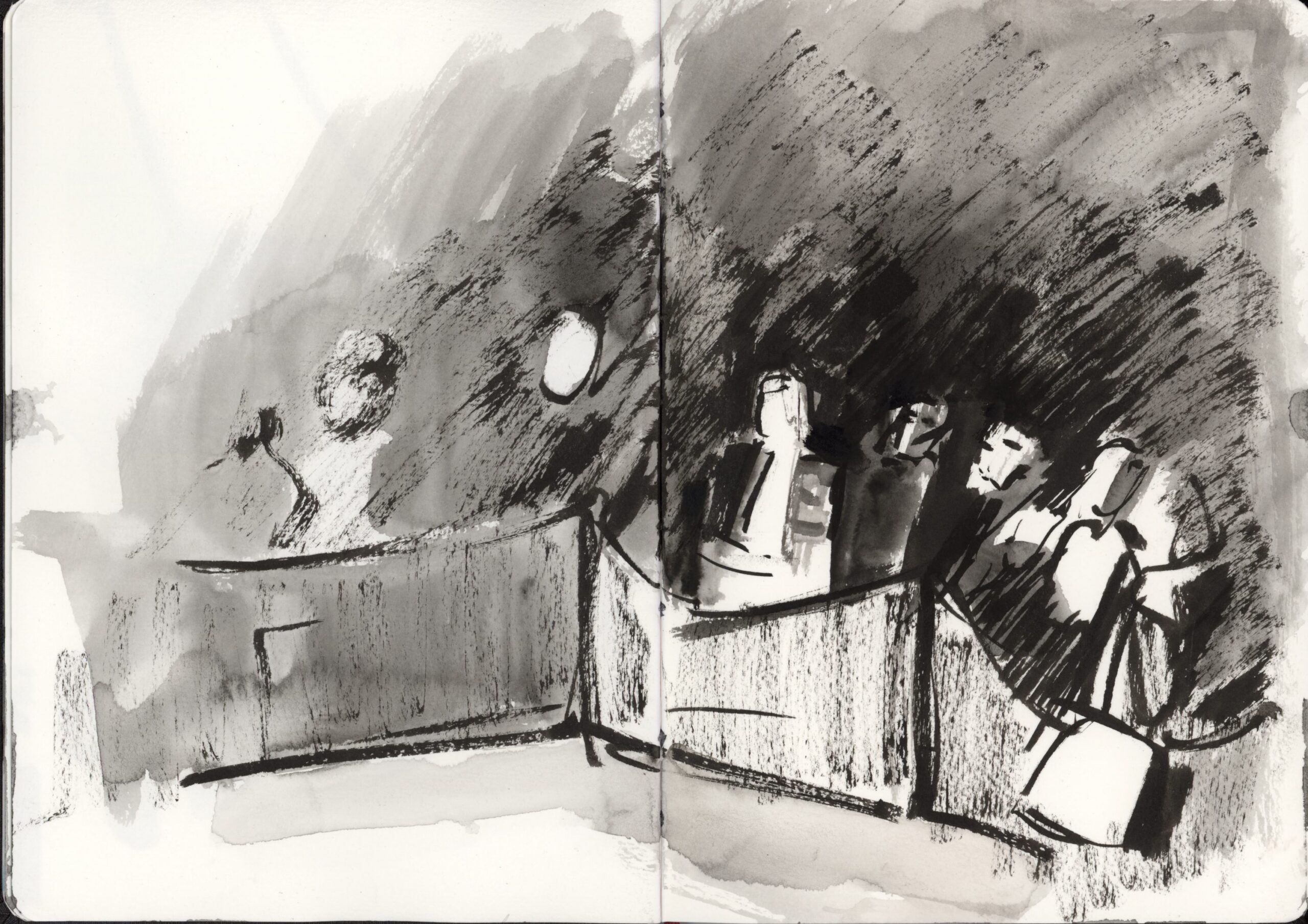

Scripted Larps and a Neo-Noir Experience

in

A scripted larp is a larp structured through a pre-defined script with some theatrical appearance. It’s a kind of Play and Enjoy Watching larp. This article shows how this works, based on my personal experience as creator of Devil in our sins, a neo-Noir scripted larp.

-

Freak Show, an Autopsy

in

Freak Show, a larp held in an abandoned amusement park in Finland. The larp told the story of the last freak show and explored otherness through a romantic gothic horror setting. The participants played a family of outcasts and freaks who struggled to survive in a hostile world. The story ended with the devil coming…

-

Playing Nasty Characters

in

Nasty characters can be important and necessary in larp; and then somebody has to play them. This article looks at the practical issues of taking on such roles; at the social and psychological implications of this kind of play; and at the important things to consider when coming out of play.

-

The Death of Hamlet – Deconstructing the Character in Enlightenment in Blood

in

In the 2017 larp Enlightenment in Blood, we created a new form of character creation tool using a software tool called Larpweaver. It’s based on the idea the larp can provide a selection of elements for the player to choose from and compile their own character.

-

Keeping the Candles Lit, When the Light Has Gone Out

in

Eclipses are funny things. They stop the world, and we all look up together, watching that constant sun slowly disappear before our very eyes. And together, we wonder, for just a moment, if the light will ever come back.

-

Safety and Calibration Design Tools and Their Uses

in

Safety & Calibration techniques are important design tools that help diverse players access your larp and create stories together. This article offers three Safety & Calibration Tools that have been in use since June 2016 and are now used internationally in a variety of larps & other events.

-

Lobbying for the Dead – Vampire larp at the European Parliament

in

Organizing the first ever larp played partially at the European Parliament gave the opportunity to explore design concepts such as indexical larp, where the fiction of the larp corresponds to actual reality as closely as possible.