Category: Documentation

-

Remember That Time… We Tried to Film a Larp

In this article, Sophia Seymour and Martine Svanevik discuss their experiences of filming a larp for a documentary.

-

Did We Wake?

Reflections on Before We Wake, a larp played in 2015, a larp which refused to let go, which insisted on being untangled…, and utterly unlike any other larp ever played.

-

Possibilities of Historical Larp: Court of Justice in 17th-century Finland

When a larp is designed based on historical sources and research, it adds to its authenticity – not just about material culture, but also about actions, experiences, and mentalities, which larp is a good tool for reenacting.

-

Out of Nothing, Something

In the larp Helicon, a specific kind of beauty spontaneously emerged when players’ actions collectively created a wonderfully coherent whole.

-

The Cliff – A Case Study of Interdisciplinary Larp Methods for Artistic Research Practice

To bring her short film The Cliff to life, Katri Lassila harnessed immersive techniques borrowed from larp, integrating them into her artistic photography process.

-

Serious Larp at the United Nations in Geneva

Account of a Serious Larp run at the United Nations in Geneva, in which 30 staff played parents designing a new school for their children.

-

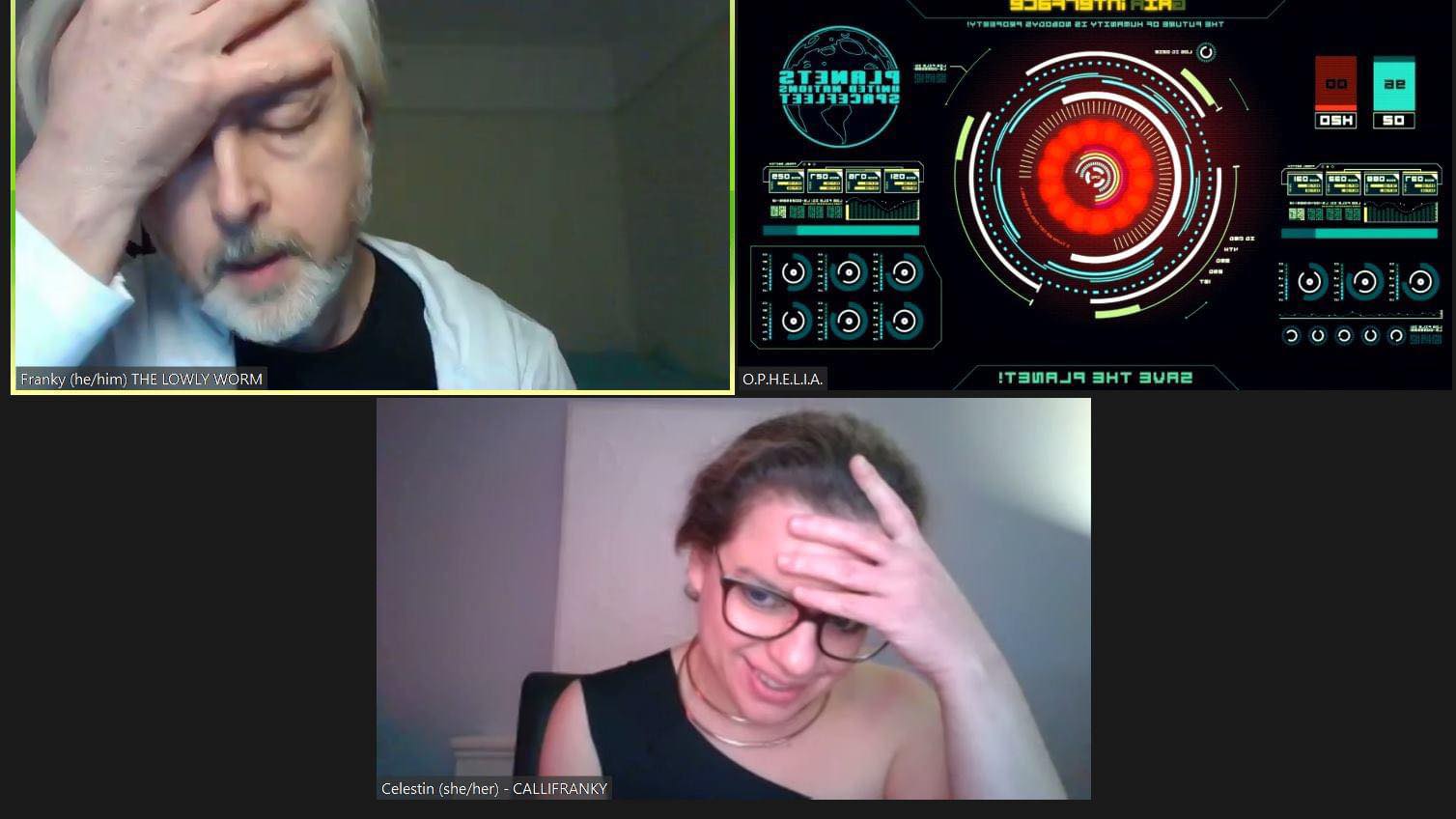

Actual Plays of Live-Action Online Games (LAOGs)

Why make recordings of larps played online? Read about the reasons for doing so, the history of the activity, and the considerations involved.

-

Extinction Now: Coming to Terms with Dissolution in End(less) Story

We live in an apocalyptic age. The blackbox larp End(less) Story taps into this mortal dread unapologetically and with compassion.