Category: Documentation

-

Games Never Played: or Composting ‘The Antarcticans’

“If larp is a co-creative practice, one that cannot exist without its players, what do we call larps that were never played? And what do we do with them? Can we still give them a life outside of ourselves, and enjoy their unpredictability?”

-

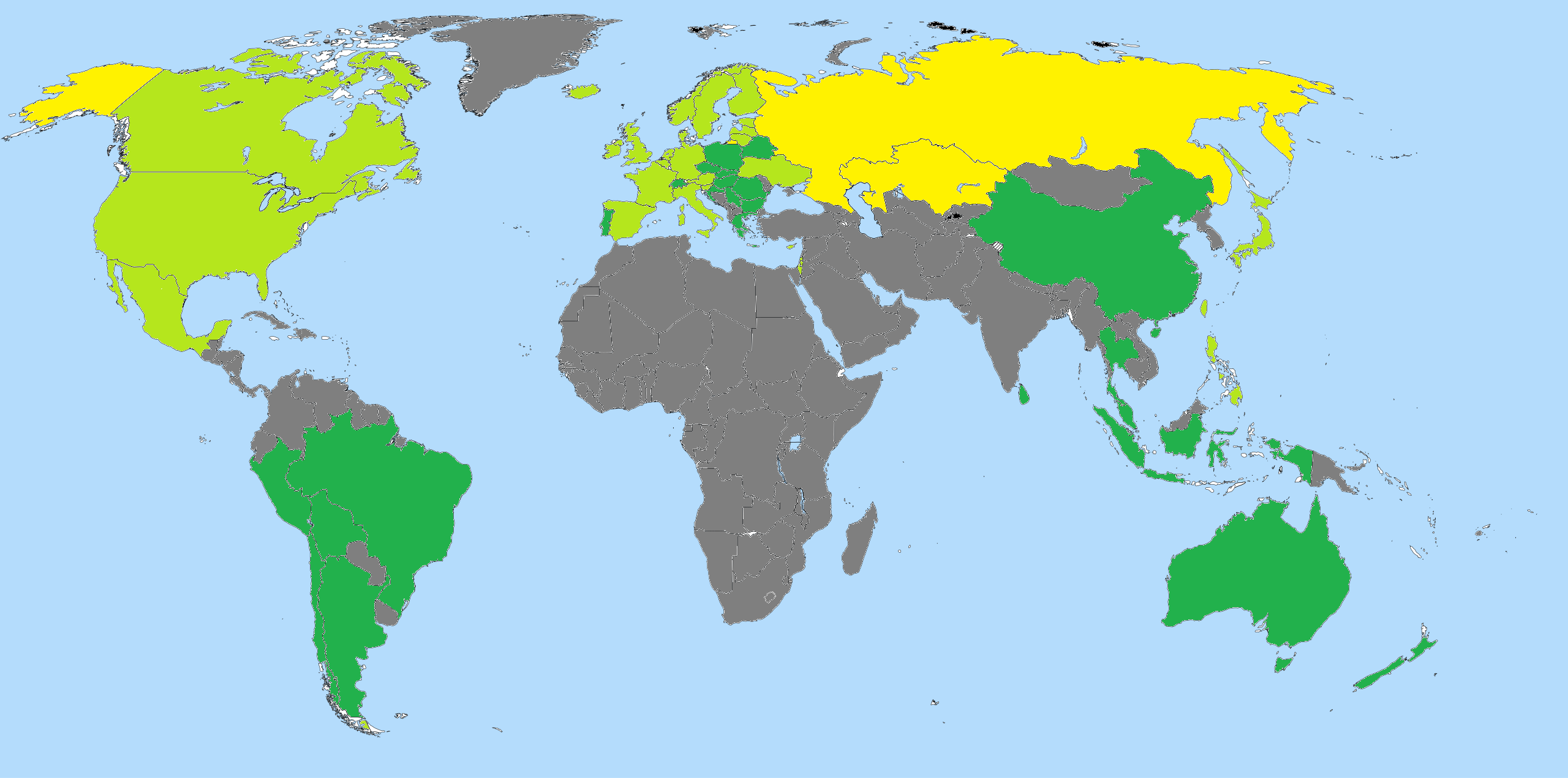

Larp in Greece, Romania, and Switzerland

A summary of the history of larping and the current larp scene in three European countries, as learned from local larpers, taken from the author’s collection of articles on larping around the world.

-

Experiencing Art from Within

In Kaisa Kangas’s larp Hyvät museovieraat (Eng. Dear Museum Visitors), in the Amos Rex museum, artworks came alive and possessed the bodies of the participants.

-

Playing First Contact in Eclipse, a Spectacular 3-day Sci-Fi Larp

The larp Eclipse “was like a simulated near-death experience, an attempt to convince players they were on the brink of unimaginable transformation,” reflects Adrian Hon, in this detailed and thoughtful article: spoiler warning!

-

Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser – The Blockbuster to End All Blockbusters

The Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser was an admirable foray into creating a larp-like experience for mass audiences on a gargantuan scale. It was not perfect, but it was far from a disaster.

-

Open Book: A Roadmap for Peer Editing

An explanation and discussion of the process by which 67 people came together to make the Knutepunkt 2025 book Anatomy of Larp Thoughts: A Breathing Corpus.

-

Snapphaneland

I’m back from waging guerrilla warfare from deep in the Swedish woods, desperately trying to keep Scania under the rightful Danish King and not the usurper Swedish crown…

-

Odysseus: In Search of a Clockwork Larp

Running a clockwork larp is a fool’s errand, because the very point of a clockwork is interdependence, and the very point of a larp is agency. The Odysseus team invested a massive amount of skilled labour to take this paradox head-on.

-

17 Years, 18 Runs, Broken Records – Why Krigslive Just Won’t Quit

An account of the long-established Danish battle larp Krigslive, including thoughts about the most recent and largest-ever event.