Tag: Palestine

-

Solmukohta 2020: Kaisa Kangas – Seaside Prison – Designing Larp for Wider Cultural Audiences

Seaside Prison is a larp about life in Gaza. In this talk we discuss the its creation, its aims, & the futures for larp in the culture establishment.

-

Playing the Stories of Others

in

Larps that treat social issues often aim to create empathy for real people who live in circumstances different from ours by putting us in their shoes.

-

Life Under Occupation: The Halat Hisar Book

Documentation of larp is an important form to share knowledge and experience about the games being run. Life Under Occupation is a book documenting the larp Halat Hisar (2013) and it was just released in digital format. We caught up the books editor Juhana Pettersson, who also was one of the larps main organizers, to ask

-

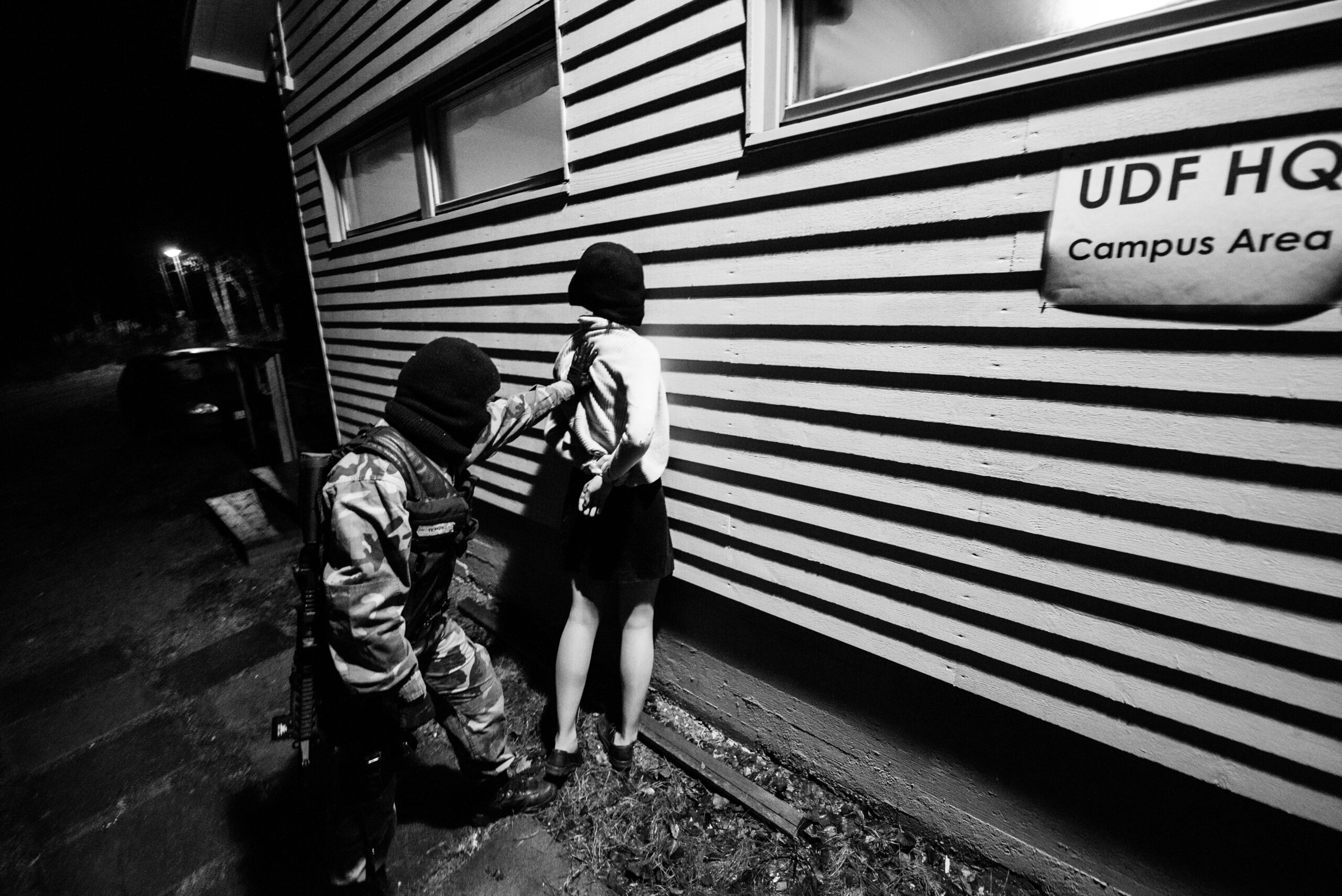

Halat Hisar Photo Report

Larper and talented photographer Tuomas Puikkonen has posted his photos from the larp Halat Hisar (State of Siege). Check them out here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/darkismus/sets/72157638504113734/

-

Sign-up Open for Halat Hisar (State of Siege)

in

Halat hisar, or State of Siege, has been covered on this site before. The sign-up for the Finnish/Palestinian cooperation has now opened: http://nordicrpg.fi/piiritystila/practical/sign-up/ Read more about the larp on their website: http://nordicrpg.fi/piiritystila/

-

New Larp Festival in Palestina

in

Beit Byout is the first larp festival in Palestine! It will be held in Ramallah from Thursday, October 3 to Saturday October 5, 2013. This is what the organizers have to say: The Festival Beit Byout will be a festival with a number of larps from Palestine and the Nordic countries. In addition there will

-

State of Siege – A Palestinian-Finnish larp project

in

Last August the larp Till Death Do us Part was organized as a cooperation between Norwegian and Palestian larp designers. It was the first bigger Palestian larp project and since then many projects has has happened in and in connection to the emerging Palestinian larp community.

-

Meeting Larp for the First Time in Lebanon

Norwegian larp organization Fantasiforbundet are doing a project in Palestinian refugee camp Rashedie in Lebanon making larp for children. Here are the words of Jacob, exiled Palestinian living in the refugee camp, talking about his first meeting with larp: Hi my name is Jacob in ordinary life, but when I play larp game I become

-

Larp Exchange Academy 2013

in

The Norwegian organization Fantasiforbundet is holding a week long event for young larp designers. It will be held in Oslo during the week leading up to the 2013 Knutepunkt conference and is eligible for participants born after October 1st 1982 and live in (or hold citizenship from) Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Czech Republic, Belarus and Palestine.