Tag: Nordic Larp

-

Extinction Now: Coming to Terms with Dissolution in End(less) Story

We live in an apocalyptic age. The blackbox larp End(less) Story taps into this mortal dread unapologetically and with compassion.

-

Helicon: An Epic Larp about Love, Beauty, and Brutality

Ritual play in which group of artists, leaders, and scientists bind the Muses of antiquity to their will.

-

A Trip Beyond the House of Craving

Larp is sometimes thought of as a consensual hallucination, and this one was more hallucinogenic than most.

-

The Immortal Legacy

A documentation piece on the larp Gothic by Avalon Larp Studios. Based on true events featuring Romantic poets in a story of gothic horror.

-

Slow Larp Manifesto

in

There are larps that are not action-heavy, that don’t try to offer maximum amounts of drama or complicated plots. Lack of action or drama in a larp is often regarded as a design fault. We think Slow Larp should be recognized as a valid design choice that deserves more attention.

-

Dragonbane Memories

We had crazy plans. We would transform fantasy larp forever. We would create the best larp in the world… or so I thought.

-

From Winson Green Prison to Suffragette: Representations of First-Wave Feminists in Larps

In this article, I present feedback on my experience playing and writing on suffragettes in larps set in early 20th century Europe. I present the diverse angles through which the theme and characters were approached in these larps and contrast their differences. These games are set up at a time period with clearly separated gender

-

What Is Nordic Larp?

in

What is Nordic larp? We’ve updated and expanded our definition of the term! We hope it’s easy to undertstand and useful for our readers.

-

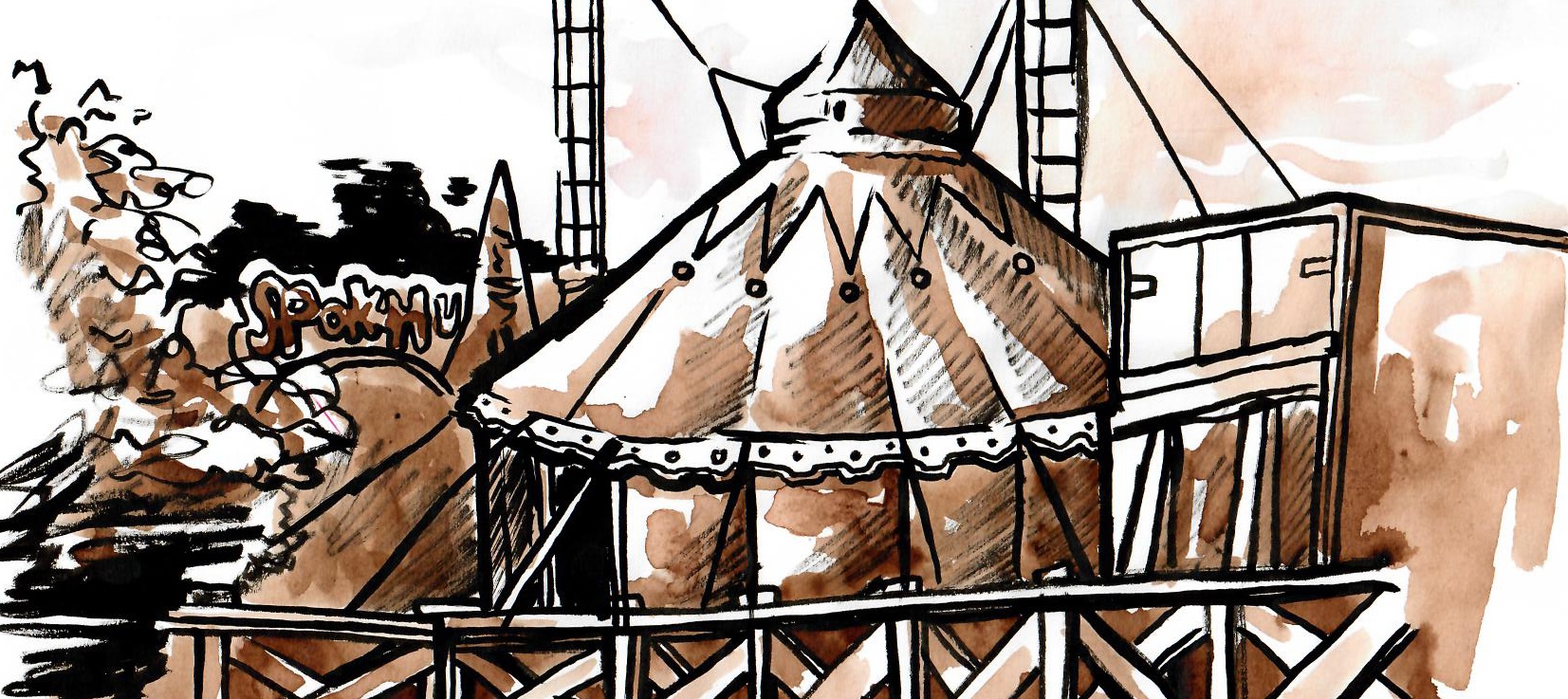

Let’s Talk Freak Show

An honest, possibly scrambled, and very emotional review and critique. Trigger warning: Contains coarse language and depictions of violent acts. In September 15-17, 2017, I attended the larp Freakshow by Nina Teerilahti, Alessandro Giovannucci, Dominika Cembala, Martin Olsson, Morgan Kollin, and Simon Brind. The larp was held in Vaasa, Finland. Pre-game painting of Charlie “Edge”

-

The Battle of Primrose Park: Playing for Emancipatory Bleed in Fortune & Felicity

Fortune & Felicity was an opportunity to immerse into a world, explore my academic interests, add to my fieldwork, and experience emancipatory bleed.