Tag: Featured

-

Photo Report: Mare Incognitum

Mare Incognitum was a Swedish Lovecraftian horror larp set on a ship (familiar to visitors to Monitor Celestra) in the 1950s. It was organized by Berättelsefrämjandet and had 78 players, spread over three runs, from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Spain, UK and the US. All three runs were held during the weekend of 28-30

-

Larp Report: Clockbottom

in

A journey through horror, steampunk and mystery Clockbottom was a larp set in America during the Civil War, with a steampunk twist and elements of horror. About 120 participants from seven different countries gathered during one weekend of September to act out the mysteries in the mining town of Clockbottom. Myself, I played the village’s

-

The Cure for the Stuffed Beast

in

The unexpected problems of a game stuffed with themes and plots and their working solutions.

-

Nordic Style Larp in the UK

in

The UK has a large and thriving larp industry, going back to the early 1980s and with an estimated 100,000+ current active participants. But awareness of larp traditions in other countries, and in the Nordic scene in particular, has been minimal until very recently. In particular, the few months since Knutpunkt 2014 have seen a flurry

-

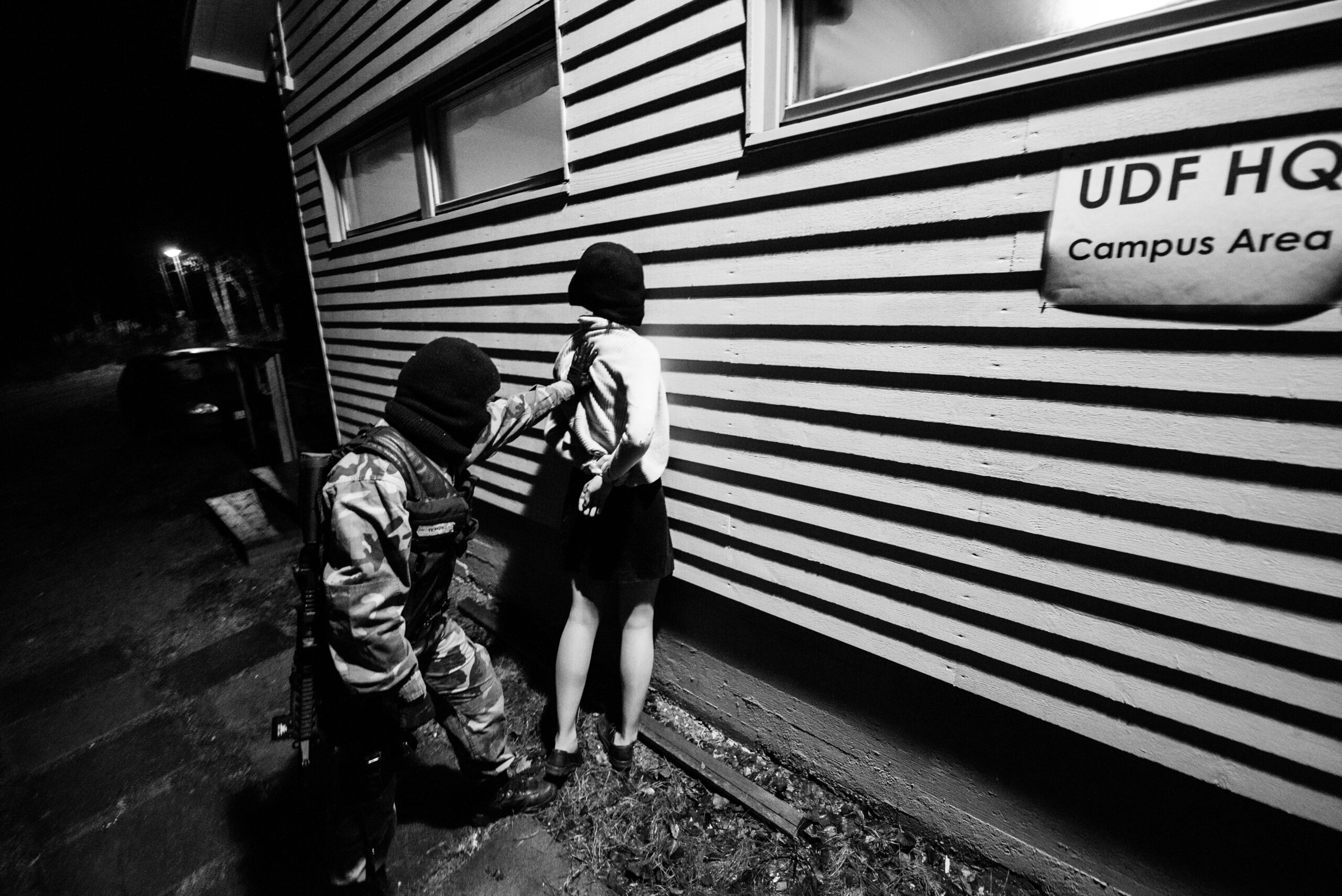

Life Under Occupation: The Halat Hisar Book

Documentation of larp is an important form to share knowledge and experience about the games being run. Life Under Occupation is a book documenting the larp Halat Hisar (2013) and it was just released in digital format. We caught up the books editor Juhana Pettersson, who also was one of the larps main organizers, to ask

-

We Don’t Abide to the Law of Jante

in

Swedish larper and writer Mia Sand replies to Sanne Harders opinion piece about the culture of the Nordic larp scene.

-

The Law of Jante in Nordic Role-playing

in

The good roleplayers exist, but is our naive egalitarianism scaring them away? A Danish writer, teacher and game designer takes a closer look.

-

Pillage the Vikings!

in

A thousand years ago, Viking warriors came out of the Nordic countries, raiding and conquering in Britain, Ireland, Atlantic and Mediterranean Europe, Russia and North America. They mercilessly pillaged the finest things they could find. Now it’s time for the rest of the world to take something back – and to help themselves to the…

-

Russian Roulette in Practice

in

This article describes the selection process used for high-resolution dramatic larp called Skoro Rassvet [Breaking Dawn] >(2012, 15 players). Its advantages and disadvantages are discussed. Knowing that we could take the risk because the number of potential candidates exceeded the number of offered roles several times over, we decided to perform an experiment and select…

-

Culture Calibration in Pre-larp Workshops

in

With a few exceptions, all larps take place in a set culture. This can be either a fictional culture or a culture based on the real world. For the previous larps where I have been part of the organizer team, we have made an effort to define the culture together with the players through a…