Tag: Featured

-

The Art of Steering – Bringing the Player and the Character Back Together

in

The rhetorics of Nordic larp often imply that role-players play in an intuitive fashion guided by the character, rarely or never contemplating their actions during the game. In reality, however, we are often keenly aware of what we are doing as our characters and why. This paper explores the practice of making in-character decisions based

-

Murder in Helsinki

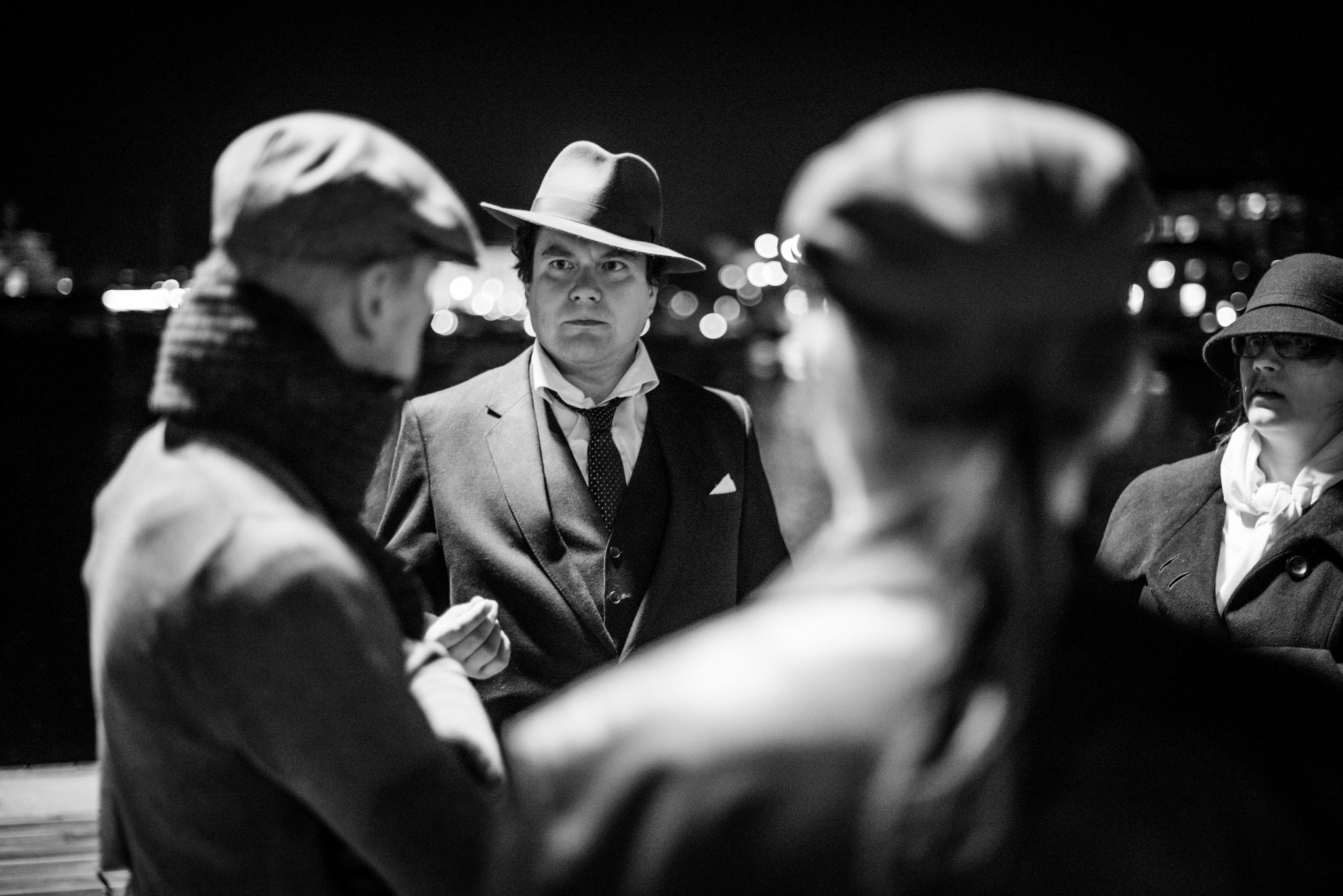

Tonnin stiflat is a Finnish larp campaign played in Helsinki in 2014. Consisting of three games, it was organized by the veteran city game designers Niina Niskanen and Simo Järvelä. The setting is Helsinki in the year 1927, and the subject matter crime, prohibition, working class life and the violent legacy of the civil war.

-

Saint Summer – A 60’s Tale of Music and Hope

Genre: Rock operaTheme: Utopia and its FallSetting: Rock’n’Roll festival in the late 1960’s, USSources: Aldous Huxley ‘The Island’, Jesus Christ Superstar, Platoon, Hair. The Messiah has been gone for two millennia. The times of rock star messiahs ended half a century ago. We have mass communication galore, but the same questions still stand. In this

-

Steering for Immersion in Five Nordic Larps – A New Understanding of Eläytyminen

in

The concept of character immersion has been a cornerstone of Nordic larp discussion for fifteen years. I was surprised by how much the concept of steering introduced last year brought to my understanding of character immersion (“eläytyminen”). In this essay I look at five specific experiences with steering towards immersion, some successful, some not. More

-

Processing Political Larps – Framing Larp Experiences with Strong Agendas

in

Thanks to it I turned my communist friend into a patriot. And I realized who I really am. This is how a respondent, according to Mochocki (2012), described the Polish tabletop role-playing game Dzikie Pola (“Wild Planes”) in an online survey. The game was set in a period of Polish history dating to 1569 –

-

Nemefrego 2014 – Old School Fantasy with New Ideas

Since 1995, the Danish non-profit organization Einherjerne has made one large fantasy larp in the summer with 100-300 participants. Every larp has built on the experiences of the earlier years, with core elements of the larp being a village surrounded by a magical forest inhabited by mythical creatures. This is the Nemefrego larp series, that

-

Painting Larp – Using Art Terms for Clarity

in

When I design scenarios, I try to use the terminology from the Nordic larp discourse. But many of thes styles “available” confuse me and my players instead of clarifying what the larps are actually about. One of the problems is that many styles are defined by what they are not, instead of what they are.

-

Morgenrøde – A Game at the Dawning of the Age of Aquarius

Morgenrøde (Morning Red) was our take on the Danish hippie movement. Through three acts, 31 players portrayed the peak of the Danish hippie community and their endeavors to establish Denmark’s first grand commune: Morgenrøde – the utopia of their dreams. Spanning the late 60’es and the early 70’es, the game showed the communes rise and

-

On Publicity and Privacy – or: How Do You Do Your Documentation?

In 2014, I conducted a survey about attitudes towards photography and video in larp. I got nearly 500 responses from many different countries, and while I would love to publish the full results here, they’re a bit long for the scope of this KP book. The numbers are available at ars-amandi.se instead, and they’re really

-

Moon – A Firefly Larp Not Exactly about Firefly

How we created a Firefly larp, not exactly about Firefly One day the world became too small for all of us. Then we started to settle other planets. Terraformation begun. Things changed. Lot of us became adventures, seeking freedom and independence. But with great power comes great responsibility… None of us had an idea of