Tag: Featured

-

Larp in Leadership Development at the Royal Norwegian Naval Academy (RNNA)

in

Naval cadets became more role flexible as a result of the use of larp in training, and those who were positively inclined gained greater benefits.

-

Let Me Look into Your Future

in

Building and using a custom set of cards for divination within a larp – embracing serendipity and creating magic.

-

10 (+1) Tips for Larpers Over 35

in

A great list of ways to use your age and experience to enhance your larping.

-

Creating Magical Romance Play

in

How do we use romantic play to deepen a character, creating an engaging story about emotions that enriches play for all parties involved.

-

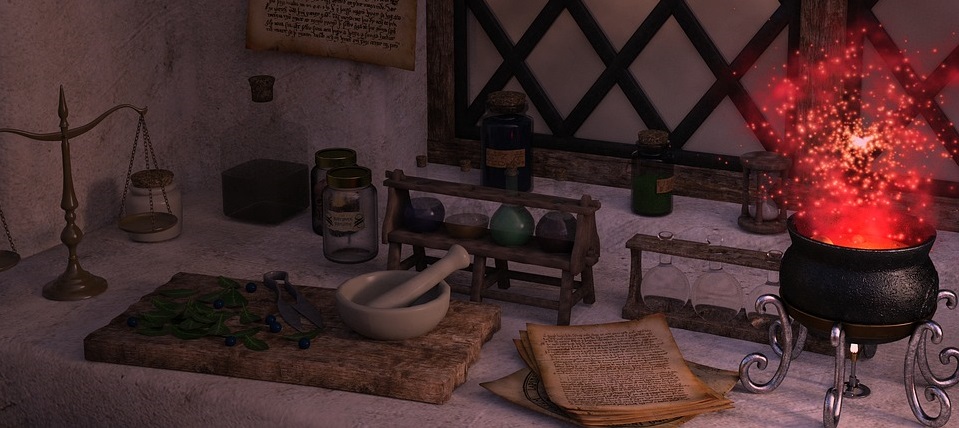

Recipe for a Magical Larp Experience

in

Mix all the ingredients — diversity, dialogue, awareness, and more — in a venue of your choice. Enjoy your magical larp experience and remember to share with your co-players.

-

Basics of Efficient Larp Production

in

An alternative mode of production to the Infinite Hours of labor often spent in larp organizing and volunteering.

-

The Magic of the Silicon Screen

in

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, mainstream larp has ventured into the magic of modern technology and what it has to offer.

-

Structured Feedback

in

How do you get feedback on your larp, and integrate it into your design process?

-

Atypical: Journeys of Neurodivergent Larpers

in

Needs and traits that must be highlighted for neurotypical players and organizers to better understand their neurodivergent counterparts.