Tag: Books

-

Open Book: A Roadmap for Peer Editing

An explanation and discussion of the process by which 67 people came together to make the Knutepunkt 2025 book Anatomy of Larp Thoughts: A Breathing Corpus.

-

Review of Larp Design: Creating Role-Play Experiences

in

The gorgeous and impressive Larp Design book is a collection of practical and useful essays for beginners as well as experienced designers.

-

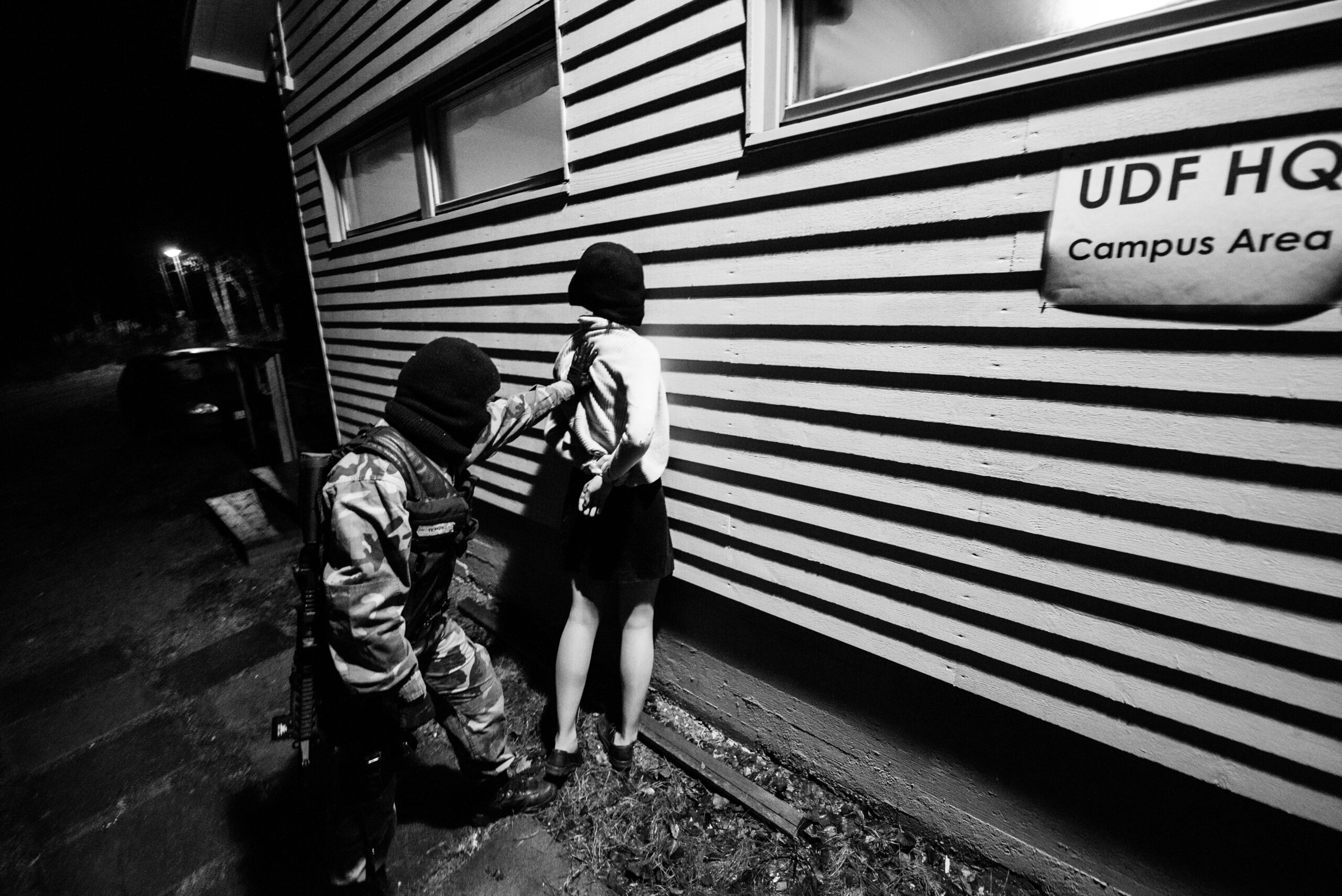

Life Under Occupation: The Halat Hisar Book

Documentation of larp is an important form to share knowledge and experience about the games being run. Life Under Occupation is a book documenting the larp Halat Hisar (2013) and it was just released in digital format. We caught up the books editor Juhana Pettersson, who also was one of the larps main organizers, to ask

-

Book Review: Larps from the Factory

Danish larper and larp designer Oliver Nøglebæk has written a review of the larp script collection book Larps from the Factory. Here is an excerpt from the review: I know how much work the creators put into making this book and it shows. It is well written and consistent, which is extra impressive considering the

-

The Larp Factory Book Pre-Order

You can now pre-order The larp Factory Book through their IndieGoGo campaign. This is how they present the project themselves: The Larpfactory Book Project will be a collection of 23 Norwegian ready-to-play larpscripts, written in English, and a website containing game materials and videos showing all methods and techniques mentioned in the book. The larps