Tag: art larp

-

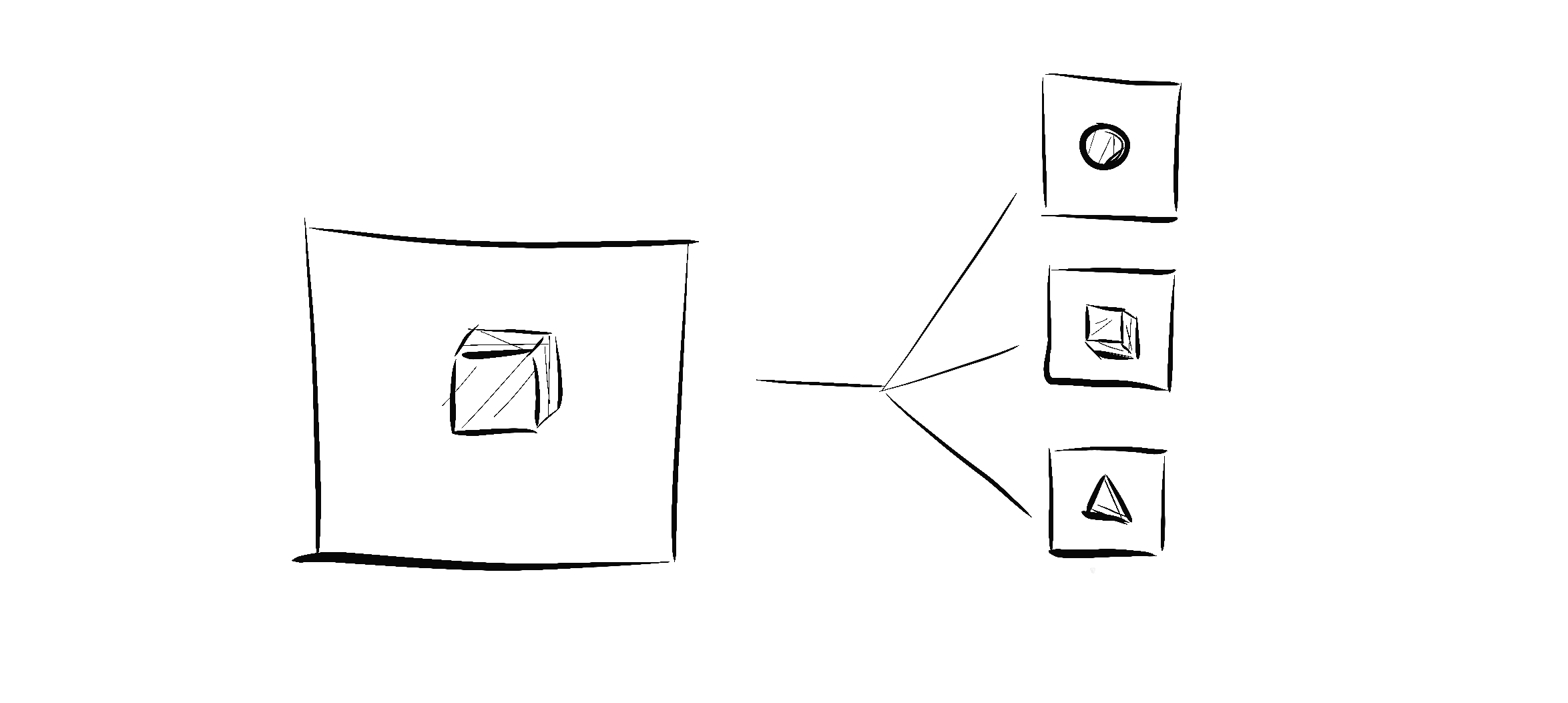

The Art-Larp Paradox

“In adapting larp practices to be suitable for artistic spaces and audiences, embodiment, and player agency is susceptible to compromise – potentially sacrificing the artistic essence of larp itself,” says Alex Brown.

-

Larp As Embodied Art

This article describes our artistic practice and design principles focusing on the bodily experience.

-

Against Design

in

Stop using experience product delivery as the primary factor when evaluating larp projects.

-

Helicon: An Epic Larp about Love, Beauty, and Brutality

Ritual play in which group of artists, leaders, and scientists bind the Muses of antiquity to their will.