Category: Opinion

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in these texts are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Nordiclarp.org or any larp community at large.

-

Jaakko Stenros: Retrospective: Documentation, Community, and Research

in

In the Knutepunkt scene there is a history of larp designers and producers giving retrospectives, where they discuss all of their work. In this talk, here presented in two parts, Dr Stenros takes that format and expands it to other aspects of the community. He gives an overview of the work he has done around

-

Imagining a Zero Carbon Future: Environmental Impact of Player Travel as a Design Choice

in

Addressing a convenient and uncomfortable blindspot of the community: aviation emissions in international larp.

-

Beyond Cracking Eggs

in

Larp made me trans; what next? A conversation between four larpers whose eggs cracked a long time ago.

-

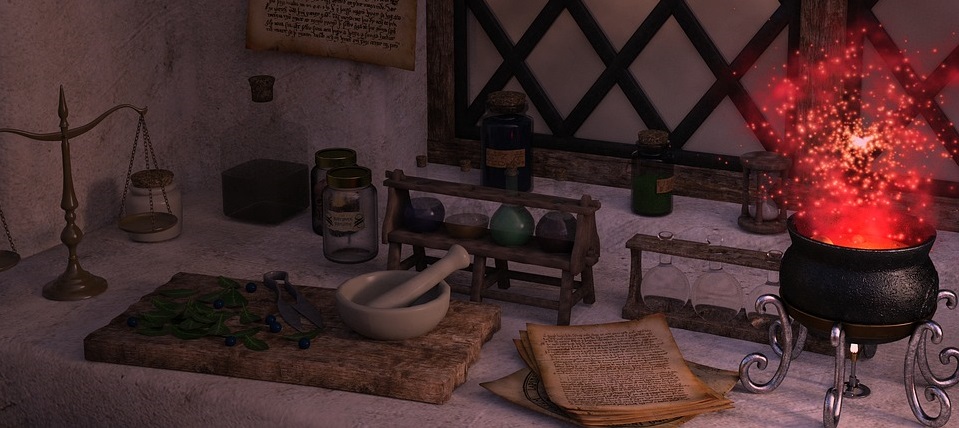

Recipe for a Magical Larp Experience

in

Mix all the ingredients — diversity, dialogue, awareness, and more — in a venue of your choice. Enjoy your magical larp experience and remember to share with your co-players.

-

Grooming in the Larp Community

in

In this opinion piece Sanne Harder explores predatory behavior in larp communities. Content Advisory: Sexual abuse, mental health issues.

-

Sex, Romance and Attraction: Applying the Split Attraction Model to Larps

in

The Split Attraction Model can be used to expand language in describing larps, in setting expectations, and in player negotiations, in order to reduce struggles and misunderstandings.

-

Larp and Prejudice: Expressing, Erasing, Exploring, and the Fun Tax

in

Designers of larps with a real-world setting face questions about how to deal with prejudice. This article looks at three possible approaches.

-

The Brave Space: Some Thoughts on Safety in Larps

in

As well as safety from unpleasant or triggering experiences, larp needs safety to lean in, to be brave, and to get the play we crave. We need brave spaces.