Category: Nordic Larp

-

Website Update 2025

in

Nordiclarp.org has been updated to modern software and moved to new, faster and better hosting. Bare with issues & report feedback to us.

-

What Is Nordic Larp?

in

What is Nordic larp? We’ve updated and expanded our definition of the term! We hope it’s easy to undertstand and useful for our readers.

-

Playing the Stories of Others

in

Larps that treat social issues often aim to create empathy for real people who live in circumstances different from ours by putting us in their shoes.

-

Call for Articles

in

We want your brilliance! Have an idea you want to share? Write for Nordiclarp.org! We accept text contributions and you can read more about our process here: https://nordiclarp.org/write-for-us/ If you don’t want to write but contribute in other ways we have some suggestions here: https://nordiclarp.org/contribute/

-

Creating a Culture of Trust through Safety and Calibration Larp Mechanics

in

When Ben Morrow and I decided to offer a College of Wizardry-like experience in North America in April 2015, we knew we had our work cut out for us. Not only did we need to form a larp production company, secure the venue, build the costumes, obtain props, find players, and all the other duties

-

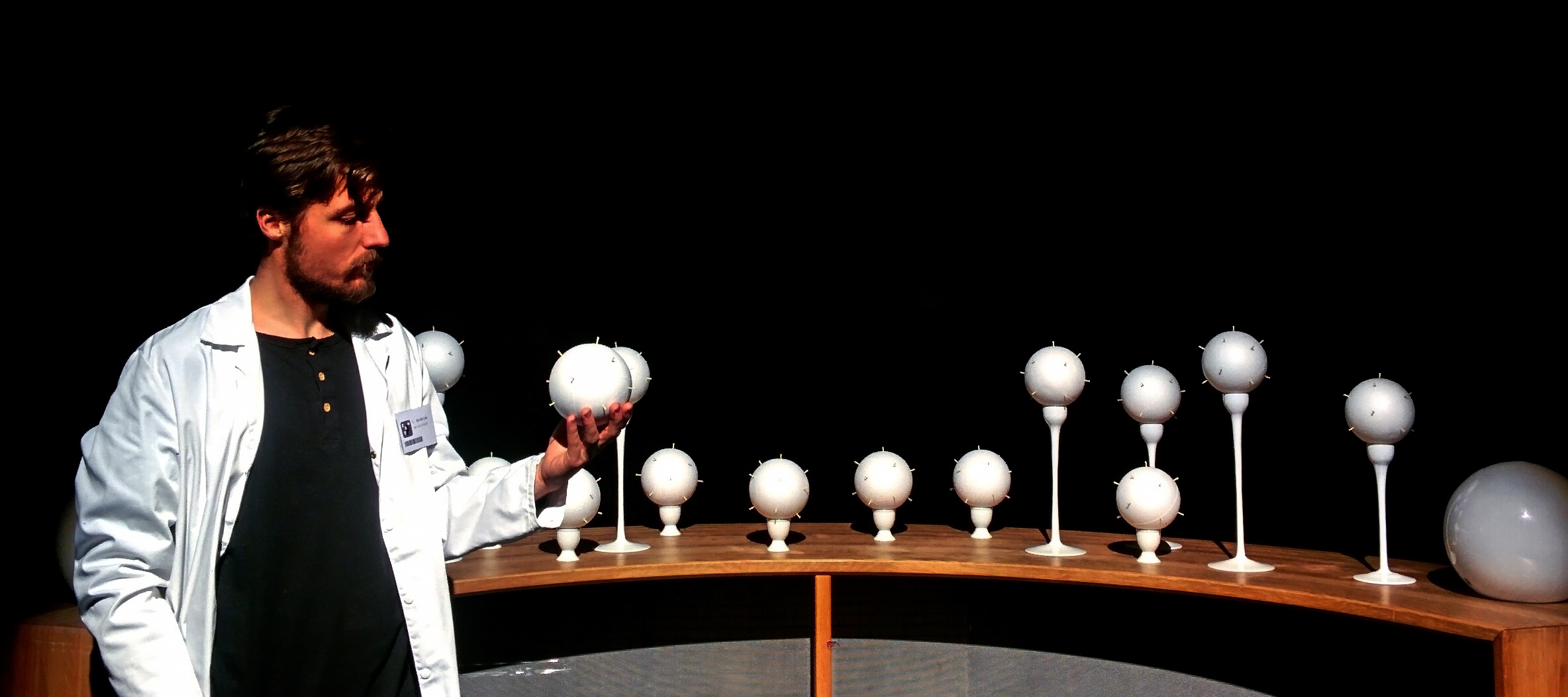

Bjarke Pedersen – Becoming the Story

in

Danish larp producer Bjarke Pedersen of Odyssé is talking at the Future of StoryTelling conference in New York in 5-6 October 2016. Here is a short talk (3m 26s) where he eloquently and concisely describes what larp is.

-

Support Nordiclarp.org on Patreon

in

You can now support Nordiclarp.org on Patreon! By giving us a monthly donation through Patreon you can help us keep the site running. Our Patreon page, linked below, further explains how to donate and where the money goes. Where Does the Money Go? In short we’ll use your money to pay our bills for running the

-

Chamber Larps and the Audience Problem

in

When attending contemporary theatre performances in the past year, I have been following closely what happens when the actors try to involve the audience in doing something. Even though the audience at these kind of performances should not be alien to some kind of interactivity, the bar seems to be extremely high for people to…

-

Play the Gay Away – Confessions of a Queer Larper

in

I guess everybody knows I’m gay, but I don’t think everybody knows I’m a queer, too. I like to incorporate gay culture into my speech and slang, and even used to flaunt my gayness, but I haven’t been able to come to grips with being queer.

-

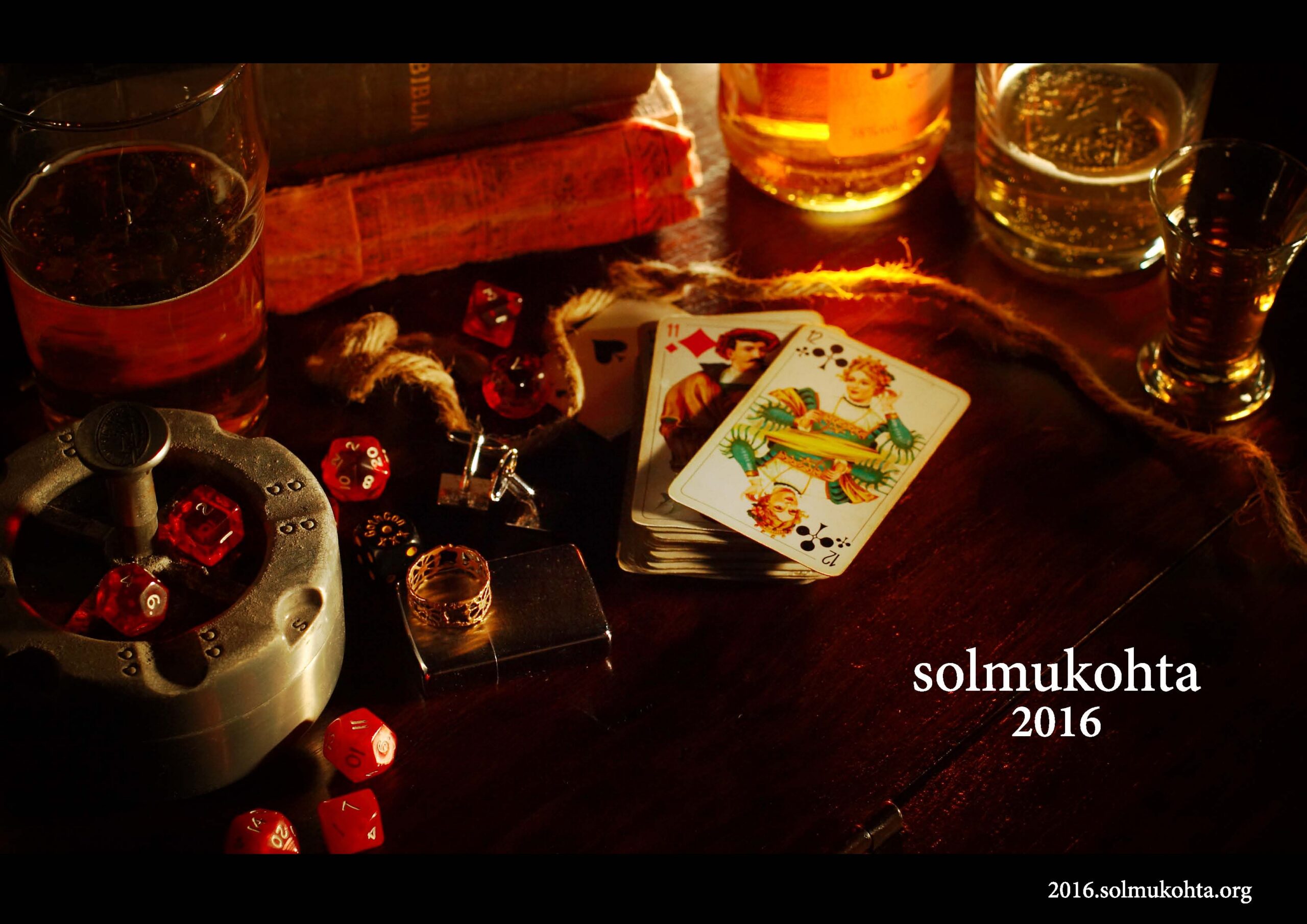

Ship Ahoy! Mark your calendar for Solmukohta 2016!

in

On Wednesday the 9th to Monday the 14th of March 2016 it’s once again time for the international roleplaying conference Solmukohta. The conference often known as Knutepunkt is this year in Finland and therefore goes by it’s Finnish name Solmukohta for 2016. This Solmukohta will be truly Baltic as the location is a Tallink Silja cruise