Category: Hearts

Designer and organiser reflections. Part of a collection of articles written as companion pieces to the larp conference Knutpunkt 2018.

-

Just a Little Lovin’ USA 2017

in

This essay recounts the organizer experience of running the Norwegian larp Just a Little Lovin’ in the USA in 2017. It specifically recounts challenges encountered with securing the site, managing controversy around the larp, and adapting it to US larpers.

-

Immerton

in

Immerton is a 4-day larp written by women for women participants, taking place in a fictional society of women in a polytheistic goddess pantheon. Produced by Learn Larp, the game used a feminist sandbox design that emphasized rituals, relationships, collaborative roleplay, and transformational experiences using a meta room, mask play, and multimedia storytelling as core…

-

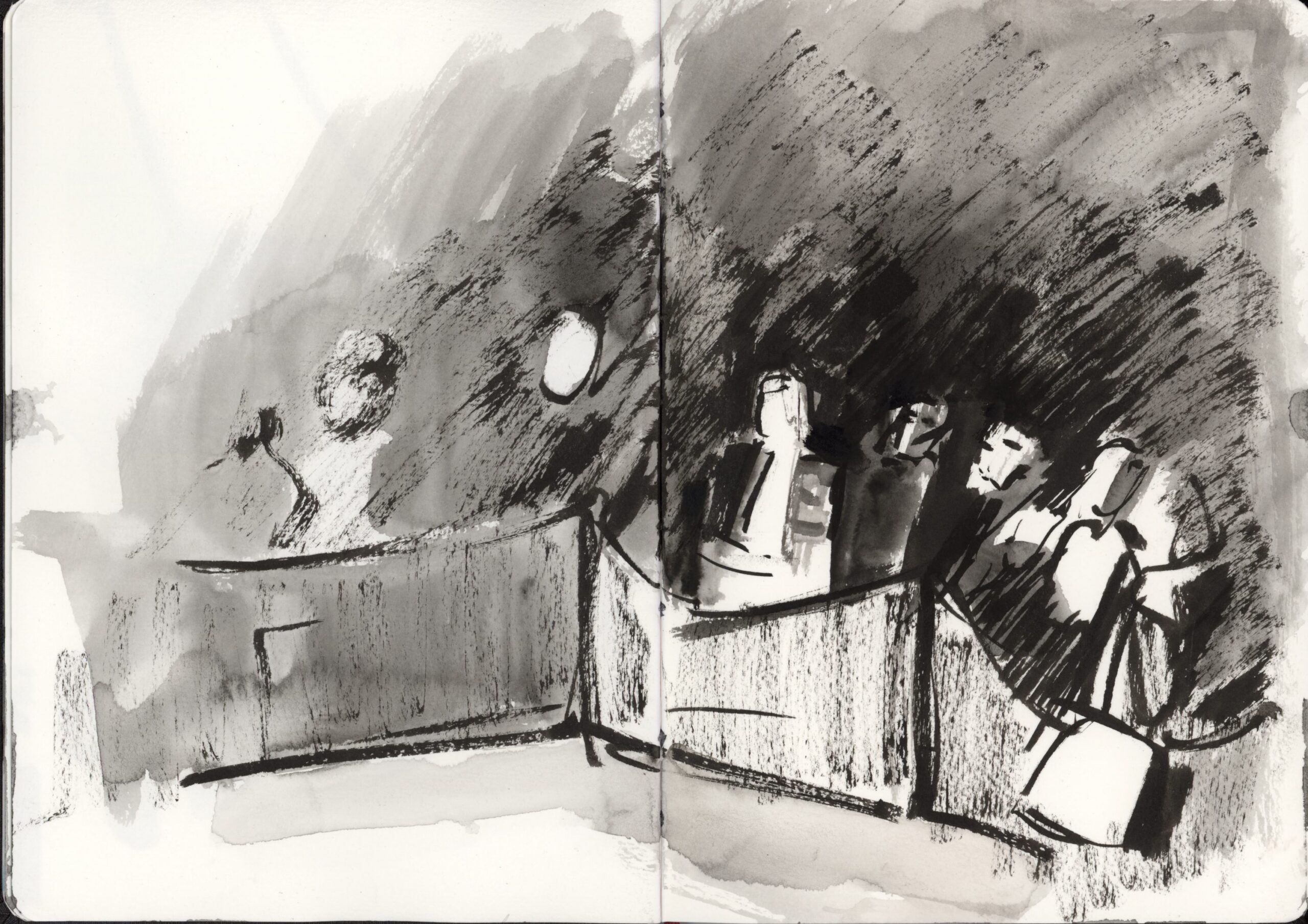

Freak Show, an Autopsy

in

Freak Show, a larp held in an abandoned amusement park in Finland. The larp told the story of the last freak show and explored otherness through a romantic gothic horror setting. The participants played a family of outcasts and freaks who struggled to survive in a hostile world. The story ended with the devil coming…

-

Keeping the Candles Lit, When the Light Has Gone Out

in

Eclipses are funny things. They stop the world, and we all look up together, watching that constant sun slowly disappear before our very eyes. And together, we wonder, for just a moment, if the light will ever come back.

-

Lobbying for the Dead – Vampire larp at the European Parliament

in

Organizing the first ever larp played partially at the European Parliament gave the opportunity to explore design concepts such as indexical larp, where the fiction of the larp corresponds to actual reality as closely as possible.