Category: Documentation

-

Infinite Firing Squads: The Evolution of The Tribunal

I accidentally created a hit, and have ever since been wondering why. I have had success with several mini-larps over the years, such as A Serpent of Ash (2006) and Prayers on a Porcelain Altar (2007), both of which keep getting the occasional rerun here and there. The Tribunal, however, is something else. It has

-

Exit 3: The Bunker – Claustro-drama

In July 2014, 30 players in the Netherlands split into two groups of 15 and allowed themselves to be all but locked up during two of the hottest days of the week. They were playing a larp game called Exit, the third installment in a series exploring interpersonal tension in enclosed spaces. This game was

-

Four Backstory Building Games You Can Play Anywhere!

One of the most difficult – but also most rewarding – parts of larp is coming up with a good character backstory. A sense of a character’s past gives great insights into how to play them in the present, for one thing; not to mention, it shines some light on where you may take them

-

De la Bête – An Expensive Beast

The beast I saw resembled a leopard, but had feet like those of a bear and a mouth like that of a lion. The dragon gave the beast his power and his throne and great authority. Revelations, 13:2, the Bible (New International Version) De la Bête (About the Beast) was a larp for 95 players,

-

Behind the Larp Census

29.751 larpers can’t (all) be wrong On January 10, 2015, 101 days after launching, the first global Larp Census closed to replies. 29,751 responses were logged from 123 different territories in 17 different languages. The data from this survey is freely available via a Creative Commons license at LarpCensus.org. Barring death, dismemberment, or debilitating drunkenness, the total

-

Brudpris

Brudpris (Bridal Price) is set in Berge, a rural village in the fictional Mo culture. The culture of Mo is inspired by Nordic rural 19th century aesthetics. They live isolated from the outside world according to their strict patriarchal honor culture.

-

Baltic Warriors: Helsinki

Baltic Warriors: Helsinki was the first in a hopefully longer series of political larps about environmental issues related to the Baltic Sea, and especially to the way oxygen depletion in the water can lead to “dead zones” in which nothing lives. These are caused by many different things, but one culprit is industrial agriculture.

-

College of Wizardry 2014 Round-up

College of Wizardry is a Harry Potter themed larp made by the organizations Rollespilsfabrikken (Denmark) and Liveform (Poland). You can read more about the individual team members at the College of Wizardry Team page. The larp is set in the beautiful Polish Czocha Castle and the first run was helt in November 2014 with follow-ups planned for April

-

Photo Report: Mare Incognitum

Mare Incognitum was a Swedish Lovecraftian horror larp set on a ship (familiar to visitors to Monitor Celestra) in the 1950s. It was organized by Berättelsefrämjandet and had 78 players, spread over three runs, from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Spain, UK and the US. All three runs were held during the weekend of 28-30

-

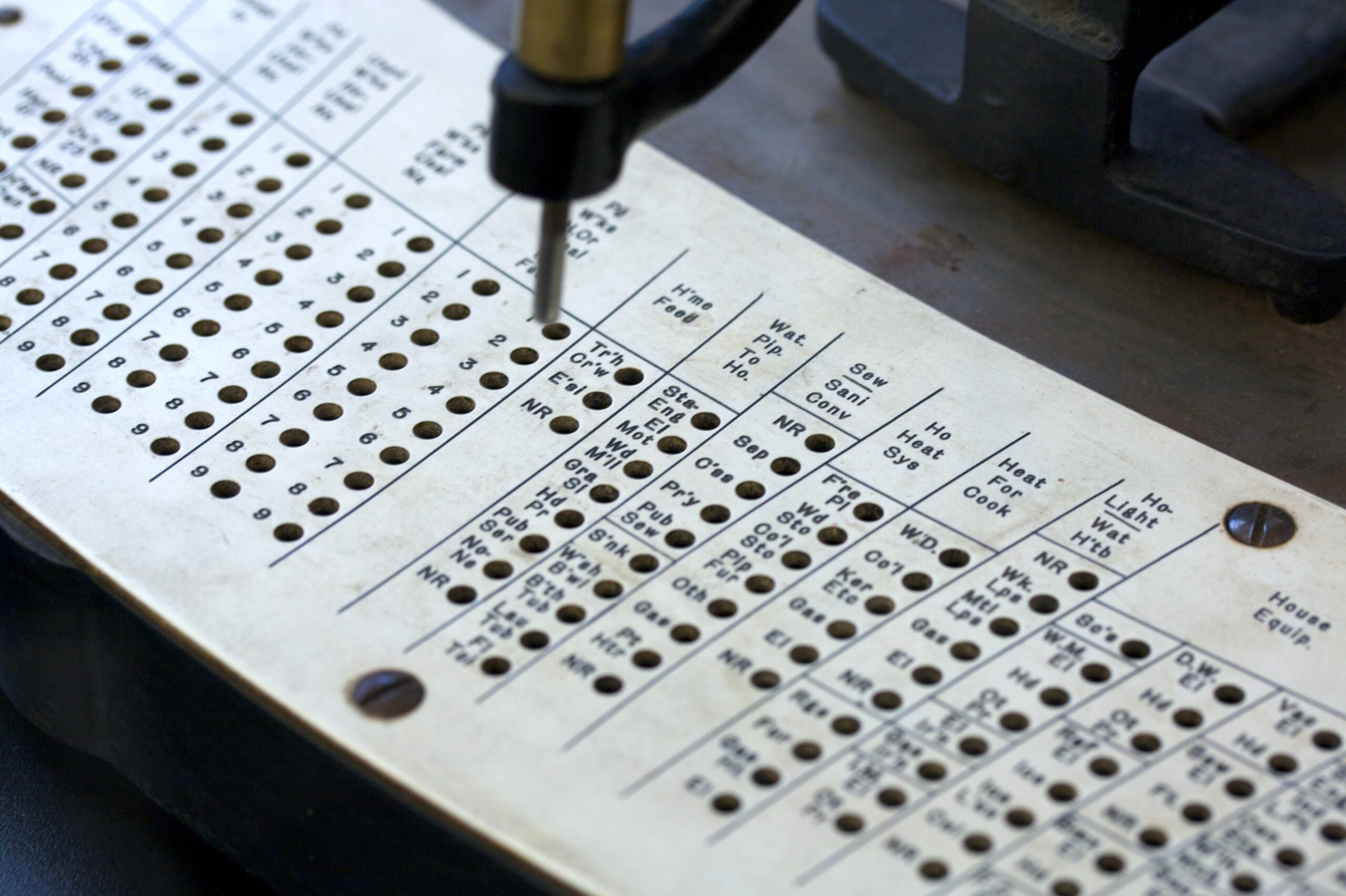

Larp Census 2014

The international larp census of 2014 has been launched, this is what the authors have to say about why you should answer it: Although some countries have rough estimates of their larp population, there has not been a comprehensive global census taken of self-identifying larpers on this scale. We really want to count everyone who