Author: Mo Holkar

-

Performance and Audience in Larp

“When we larp, some of the time we are in a performing role, and some of the time in an audience role. And that is ok! It’s the same in real life, after all. We shouldn’t see this as larp falling short of an aesthetic ideal in which such concepts don’t apply. Larp doesn’t have…

-

Flagging: A Response

in

While flagging is not perfect, it addresses manifest abusive behaviour from predatory individuals within the increasingly internationalizing larp community.

-

Challenging the Popularized Narrative of History

in

The popular version of history will always be tempting for larp designers to draw upon – but it brings a load of cultural baggage and assumptions.

-

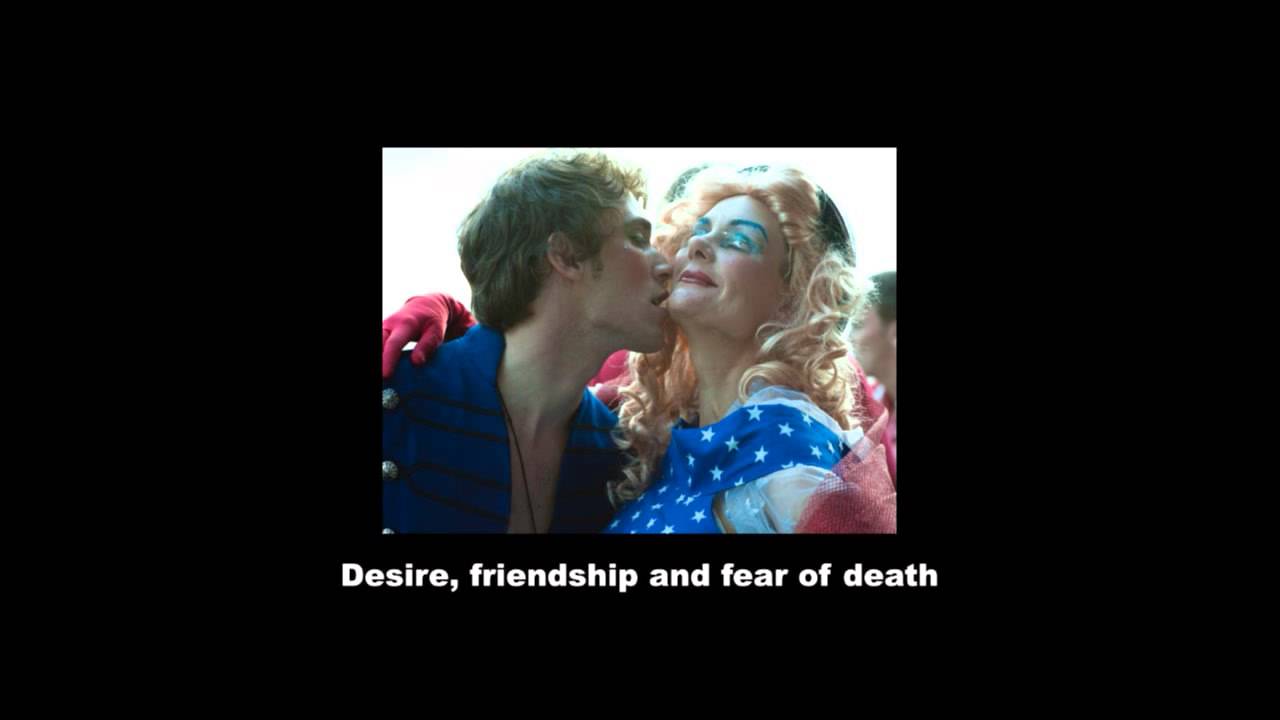

Bringing Larp to the Larpers

Katrine Wind has worked with local producers to re-run Daemon in different countries. In this presentation she shares her experiences together with some of the collaborators: Sandy Bailly who is the producer of the Belgian run and Mo Holkar who is the safety person.

-

Larping Before the Larp: The Magic of Preparatory Scenes

in

How short facilitated scenes larped during workshops can enhance play.

-

Inner Tension

Thinking about internal identities can be a way to quickly and easily generate internal tension.

-

Larp and Prejudice: Expressing, Erasing, Exploring, and the Fun Tax

in

Designers of larps with a real-world setting face questions about how to deal with prejudice. This article looks at three possible approaches.

-

History, Herstory and Theirstory: Representation of Gender and Class in Larps with a Historical Setting

in

History can be an amazing source of settings for larp! Here are some ways to make sure you’re doing justice to the underprivileged of the past and of today.

-

Real Men – Defining Gender Identities

Take your mind back, I don’t know when Sometime when it always seemed To be just us and them Girls that wore pink And boys that wore blue Boys that always grew up better men Than me and you Joe Jackson, Real Men Real Men is a chamber larp for 4–8 players, lasting four hours,