Tag: USA

-

Savoring Sameness: Hamburger larps

in

Whereas a blockbuster larp might be compared to attending a Broadway show one time, a hamburger larp is the pub you go to after work, or the community center at which you meet your friends on weekends.

-

The Operations Behind the Road Trip Experience

in

In 2017 I was the business operations lead for the Roadtrip “rock band” larp that traveled across the United States, and never before have I dealt with such unique operations related complications in my life. The Roadtrip Experience was a joint project between the Imagine Nation Collective and Dziobak Larp Studios. In this pervasive larp

-

YouTube and Larp

Mo Mo O’brien shares how she accidentally became a YouTube celebrity and offers some tips on how you can successfully create videos about larp.

-

The Absence of Disabled Bodies in Larp

in

How can we have our larps be inclusive for disabled participants? Shoshana Kessock explores ableism and solutions for larp designers and communities.

-

Let’s Fight – In Defense of Competitive Play, Part 1

in

Collaboration is in vogue. In Nordic circles and in blockbuster games, non-competitive play is ascendant. Matthew Webb argues for competetive play in larp.

-

When Trends Converge – The New World Magischola Revolution

New World Magischola is an American blockbuster larp by Learn Larp LLC about students & faculty attending a wizard university in a new US magical universe.

-

Chasing Bleed – An American Fantasy Larper at Wizard School

This article describes how I felt about my experience as someone who comes from an American campaign boffer fantasy larp background taking part in a Nordic style larp.

-

The Golden Cobra Challenge: Amateur-Friendly Pervasive Freeform Design

Once upon a time – actually, at GenCon 2014 in Indianapolis, USA – several of us discovered a design problem for live freeform games. For the last five years, the independent role-playing game scene here in North America has run an expanding series of crowdsourced events under the banner of Games on Demand. Players show…

-

Four Backstory Building Games You Can Play Anywhere!

One of the most difficult – but also most rewarding – parts of larp is coming up with a good character backstory. A sense of a character’s past gives great insights into how to play them in the present, for one thing; not to mention, it shines some light on where you may take them

-

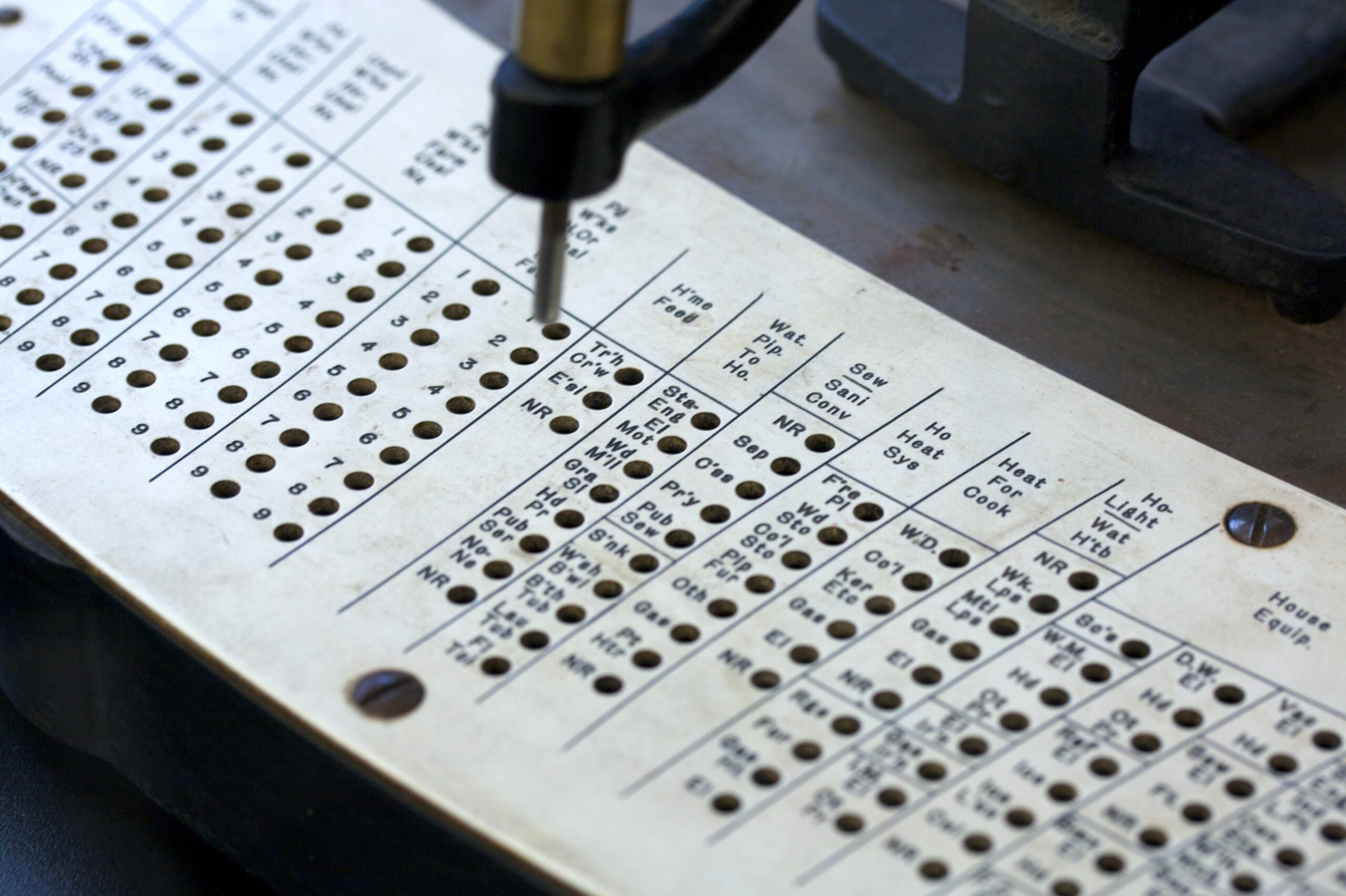

Behind the Larp Census

29.751 larpers can’t (all) be wrong On January 10, 2015, 101 days after launching, the first global Larp Census closed to replies. 29,751 responses were logged from 123 different territories in 17 different languages. The data from this survey is freely available via a Creative Commons license at LarpCensus.org. Barring death, dismemberment, or debilitating drunkenness, the total