Tag: Larp Theory

-

Painting Larp – Using Art Terms for Clarity

in

When I design scenarios, I try to use the terminology from the Nordic larp discourse. But many of thes styles “available” confuse me and my players instead of clarifying what the larps are actually about. One of the problems is that many styles are defined by what they are not, instead of what they are.

-

Now That We’ve Walked the Walk – Some New Additions to the Larp Vocabulary

in

Larp is traditionally participatory in nature. Fortunately, there’s been a great introspective and analytical tradition accompanying the continuing push against the ever moving boundaries of what’s possible and what’s been attempted. Yet it seems that our vocabulary has not grown at the same rate as the art form itself. This article will attempt to cover

-

Learning by Playing – Larp As a Teaching Method

in

Tell me, and I will forget.Show me and I may remember.Involve me, and I will understand. Confucius The next generation of teachers will be expected to possess a broad spectrum of competencies and skills. They are faced with a seemingly impossible task: today, classroom instruction should teach not only content but also competence. It should

-

Bleed: The Spillover Between Player and Character

in

Participants often engage in role-playing in order to step inside the shoes of another person in a fictional reality that they consider “consequence-free.” However, role-players sometimes experience moments where their real life feelings, thoughts, relationships, and physical states spill over into their characters’ and vice versa. In role-playing studies, we call this phenomenon bleed.((Markus Montola,

-

Ingame or Offgame? Towards a Typology of Frame Switching Between In-character and Out-of-character

in

For the Moscow and St. Petersburg larp communities, continuous immersion into the game and into the character seems to be the central point of the larp process. Larp rules proclaim continuity of game, and players generally disapprove one’s going out of the character while playing. This attitude is, however, more declarative than a reflection of

-

Six Levels of Substitution

in

The Behaviour Substitution Model You are gliding over the parquet, in a constant battle over who’s in charge. You lock eyes and tighten your grip pulling your partner just a bit closer. Your posture and precise footwork radiate confidence. Other players are holding their breath to see which one gives up the battle first. Actually,

-

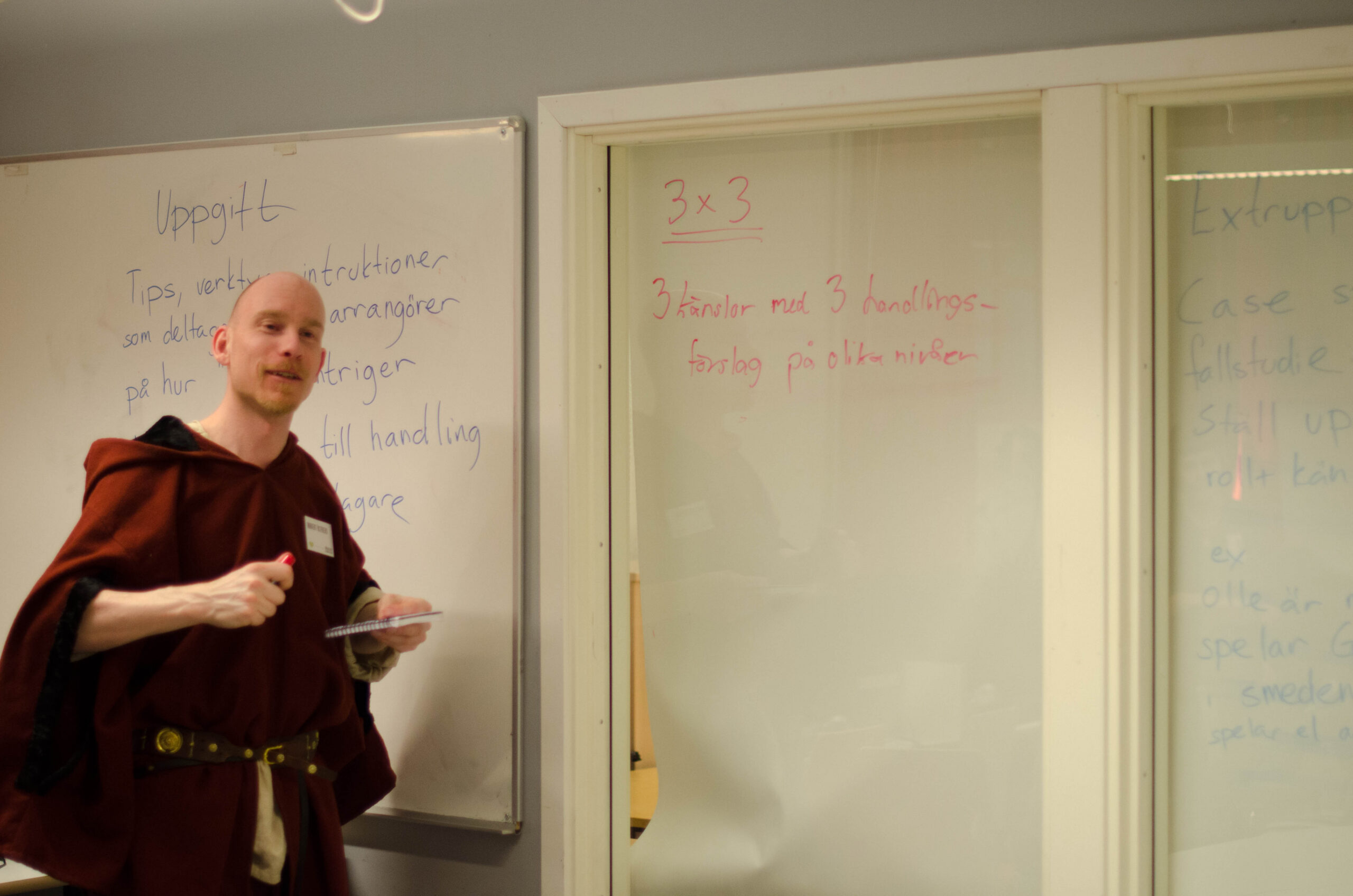

Larp Design: Theory and Practice

In this great talk at Knutpunkt 2014, larpwright Eirik Fatland give a very good breadown of larp design. Why do people do the stuff they do at larps, and how can you make them do other, more interesting, things? Characters! Relationships! Dramaturgy! A primer on what we think we know about larp design. The lecturer

-

Larpwriters Winter Retreat 2014

in

Bjarke Pedersen is organizing a retreat for experienced larpwrights to exchange experiences and ideas about larp theory. He has this to say about it: It came to me: If I could gather some of the brightest minds of larp for a weekend of talks, we might all leave the retreat better at understanding our craft,