Tag: Finland

-

The Last Ropecon at Dipoli

Ropecon is a Finnish roleplaying game convention. It’s also been something that’s been a part of my life for twenty years now. It was first organized in 1994, but I missed the initial years. I’m pretty sure my first Ropecon was 1996. I was sixteen and had just discovered Werewolf: the Apocalypse. I had made

-

Baltic Warriors Tallinn

I work as a larp producer in the Baltic Warriors project, and first game of our summer season was played last Saturday in Tallinn. It’s quite intimidating to go another country to do a game there. I had never even played in an Estonian larp, but it seemed to go well. This summer, we’re doing

-

Murder in Helsinki

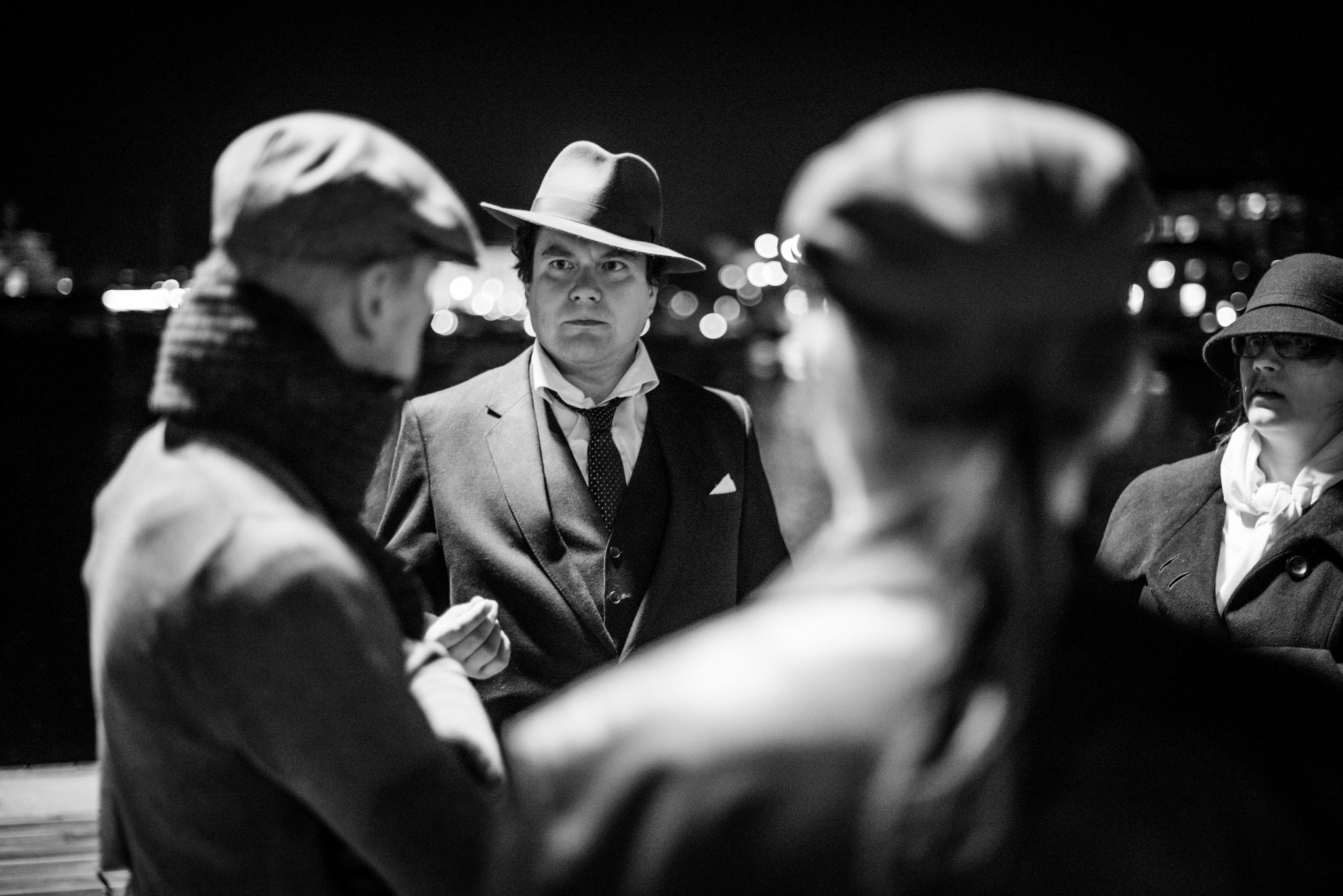

Tonnin stiflat is a Finnish larp campaign played in Helsinki in 2014. Consisting of three games, it was organized by the veteran city game designers Niina Niskanen and Simo Järvelä. The setting is Helsinki in the year 1927, and the subject matter crime, prohibition, working class life and the violent legacy of the civil war.

-

Processing Political Larps – Framing Larp Experiences with Strong Agendas

in

Thanks to it I turned my communist friend into a patriot. And I realized who I really am. This is how a respondent, according to Mochocki (2012), described the Polish tabletop role-playing game Dzikie Pola (“Wild Planes”) in an online survey. The game was set in a period of Polish history dating to 1569 –

-

Looking at You – Larp, Documentation and Being Watched

So far, Nordic larp has produced two games that have become international news stories that all kinds of sites cannibalize and copy from each other: the Danish 2013 rerun of Panopticorp, and the Polish-Danish Harry Potter game College of Wizardry. In both cases, the attention was fueled by solid documentation and good video from the

-

Infinite Firing Squads: The Evolution of The Tribunal

I accidentally created a hit, and have ever since been wondering why. I have had success with several mini-larps over the years, such as A Serpent of Ash (2006) and Prayers on a Porcelain Altar (2007), both of which keep getting the occasional rerun here and there. The Tribunal, however, is something else. It has

-

A Beginner’s Guide to Handling the Knudeblues

in

A beginner’s guide to handling the Knudeblues, the emotional drop felt after larp cons such as Knudepunkt. This text gives you tips to help you land.

-

Six Levels of Substitution

in

The Behaviour Substitution Model You are gliding over the parquet, in a constant battle over who’s in charge. You lock eyes and tighten your grip pulling your partner just a bit closer. Your posture and precise footwork radiate confidence. Other players are holding their breath to see which one gives up the battle first. Actually,

-

Baltic Warriors: Helsinki

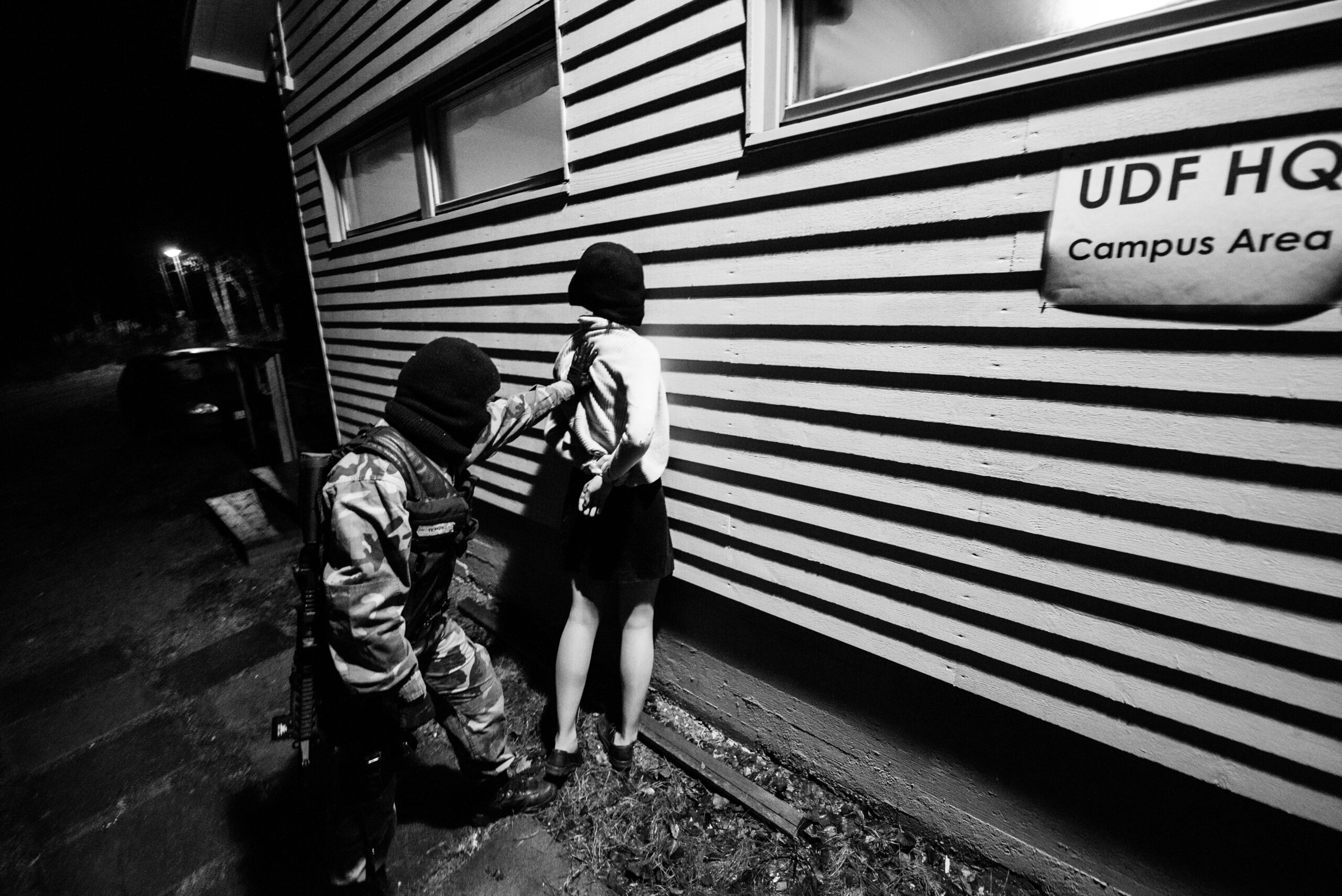

Baltic Warriors: Helsinki was the first in a hopefully longer series of political larps about environmental issues related to the Baltic Sea, and especially to the way oxygen depletion in the water can lead to “dead zones” in which nothing lives. These are caused by many different things, but one culprit is industrial agriculture.

-

Life Under Occupation: The Halat Hisar Book

Documentation of larp is an important form to share knowledge and experience about the games being run. Life Under Occupation is a book documenting the larp Halat Hisar (2013) and it was just released in digital format. We caught up the books editor Juhana Pettersson, who also was one of the larps main organizers, to ask