Tag: Finland

-

Experiencing Art from Within

In Kaisa Kangas’s larp Hyvät museovieraat (Eng. Dear Museum Visitors), in the Amos Rex museum, artworks came alive and possessed the bodies of the participants.

-

Seeds of Hope: How to Intertwine Larp and Ecological Activism

in

What could we bring into larp from the climate crisis? And what can we take home that could have an actual influence on how we act to mitigate the disaster we are living in?

-

Odysseus: In Search of a Clockwork Larp

Running a clockwork larp is a fool’s errand, because the very point of a clockwork is interdependence, and the very point of a larp is agency. The Odysseus team invested a massive amount of skilled labour to take this paradox head-on.

-

Possibilities of Historical Larp: Court of Justice in 17th-century Finland

When a larp is designed based on historical sources and research, it adds to its authenticity – not just about material culture, but also about actions, experiences, and mentalities, which larp is a good tool for reenacting.

-

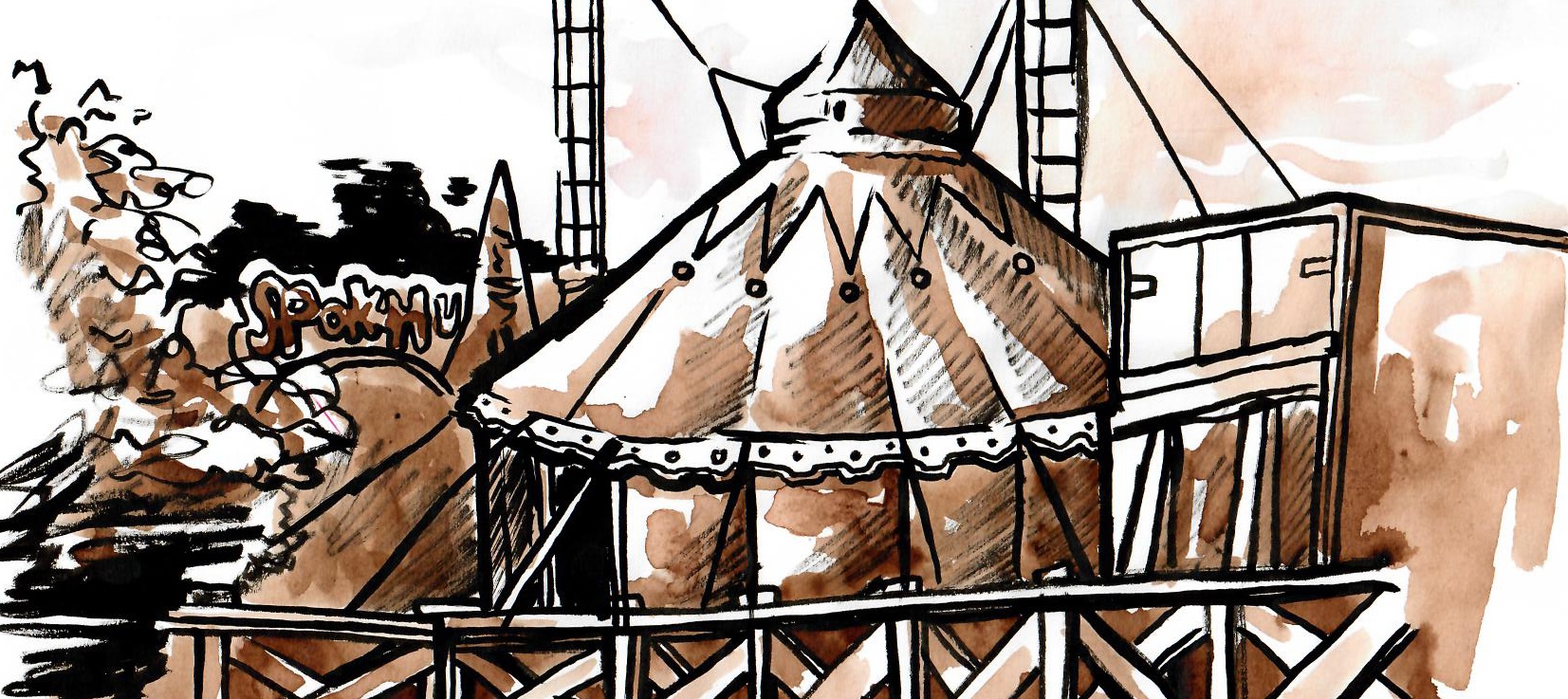

Freak Show, an Autopsy

in

Freak Show, a larp held in an abandoned amusement park in Finland. The larp told the story of the last freak show and explored otherness through a romantic gothic horror setting. The participants played a family of outcasts and freaks who struggled to survive in a hostile world. The story ended with the devil coming…

-

Let’s Talk Freak Show

An honest, possibly scrambled, and very emotional review and critique. Trigger warning: Contains coarse language and depictions of violent acts. In September 15-17, 2017, I attended the larp Freakshow by Nina Teerilahti, Alessandro Giovannucci, Dominika Cembala, Martin Olsson, Morgan Kollin, and Simon Brind. The larp was held in Vaasa, Finland. Pre-game painting of Charlie “Edge”

-

Playing the Stories of Others

in

Larps that treat social issues often aim to create empathy for real people who live in circumstances different from ours by putting us in their shoes.

-

End of the Line: White Wolf’s First Official Nordic-Style Larp

End of the Line is the first official Nordic larp under the One World of Darkness produced by White Wolf and Odyssé since the IP was acquired by Paradox Entertainment.

-

Nordic Larp Talks Helsinki 2016

in

Nordic Larp Talks is a series of short, entertaining, thought-provoking and mind-boggling lectures about projects and ideas from the tradition of Nordic Larp. This year Nordic Larp Talks will be hosted in Helsinki, Tuesday March 8th at 19:00 and you are of course more than welcome to join us! The event will be held at Aalto University School

-

Ship Ahoy! Mark your calendar for Solmukohta 2016!

in

On Wednesday the 9th to Monday the 14th of March 2016 it’s once again time for the international roleplaying conference Solmukohta. The conference often known as Knutepunkt is this year in Finland and therefore goes by it’s Finnish name Solmukohta for 2016. This Solmukohta will be truly Baltic as the location is a Tallink Silja cruise