Tag: Feminism

-

We Were Always Here: Representation, Queer Erasure, and Use of History in Larp

in

How historical larps with traditional design conventions can leave queer players feeling deeply alienated.

-

From Winson Green Prison to Suffragette: Representations of First-Wave Feminists in Larps

In this article, I present feedback on my experience playing and writing on suffragettes in larps set in early 20th century Europe. I present the diverse angles through which the theme and characters were approached in these larps and contrast their differences. These games are set up at a time period with clearly separated gender

-

#Feminism – Reviewing the Nano-Game Anthology

A couple of months ago, I received my copy of “#Feminism: A nano-game anthology”. I took me only two days to read all the games and I was so excited about testing a lot of them.

-

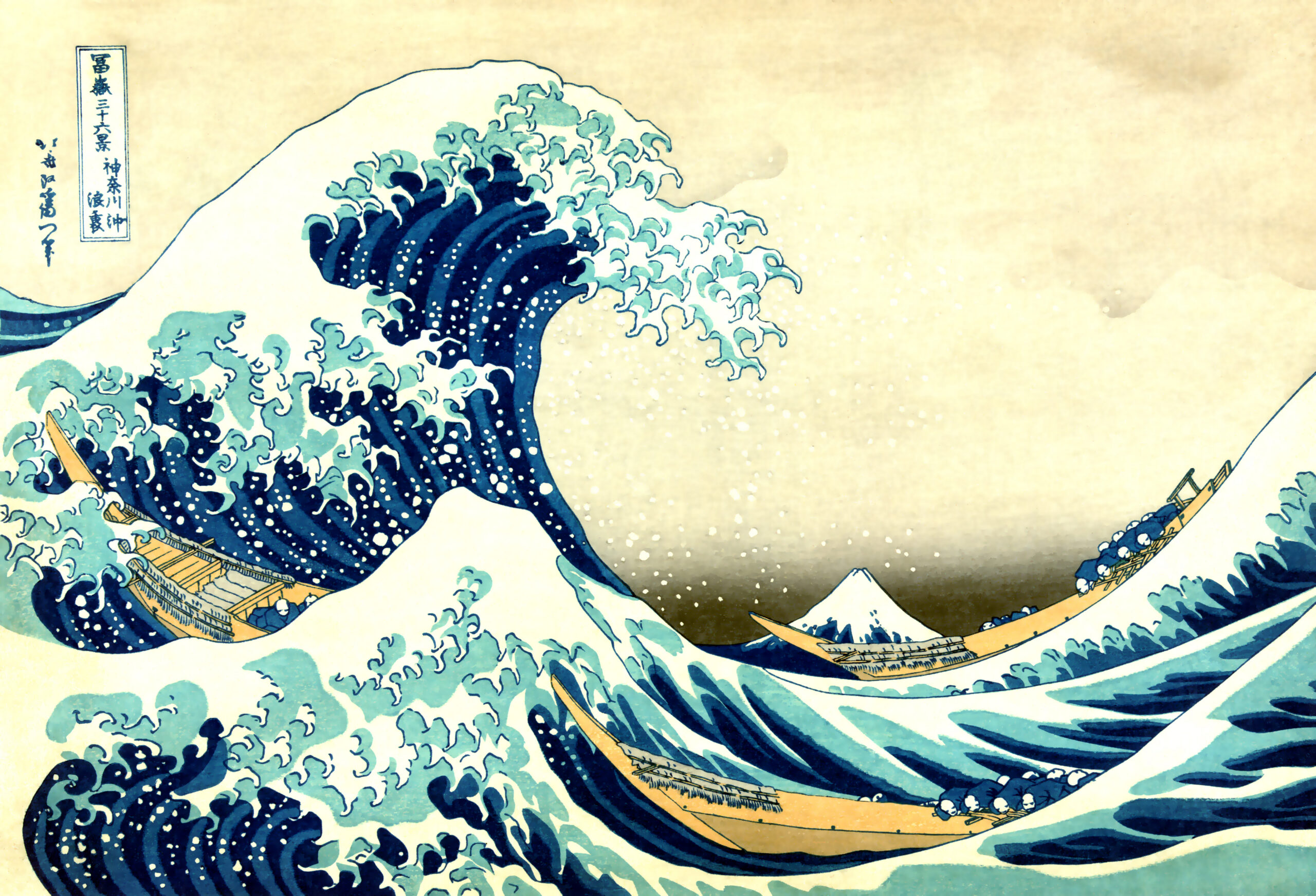

A Tsunami of Testimonies

in

Kristin Nilsdotter Isaksson has written an article, translated from Swedish by Charlie Charlotta Haldén, on the ongoing discussions about sexual assault within the Swedish larp community. On June 17, 2014, a new Facebook group was created for Swedish-speaking larpers who identify wholly or partially as women. The idea was to create a sanctuary for discussions