Tag: Edularp

-

Design for young adult players: The relevance of designing for hope, agency and inclusion

in

How can larp designers include young adults as co-creators and peers in the design and play processes?

-

Solmukohta 2020: 500 Magic Schools for Children and Youth

This panel brings together NGOs, companies and other entities that run magic schools for kids and youth; presenting themselves and their work.

-

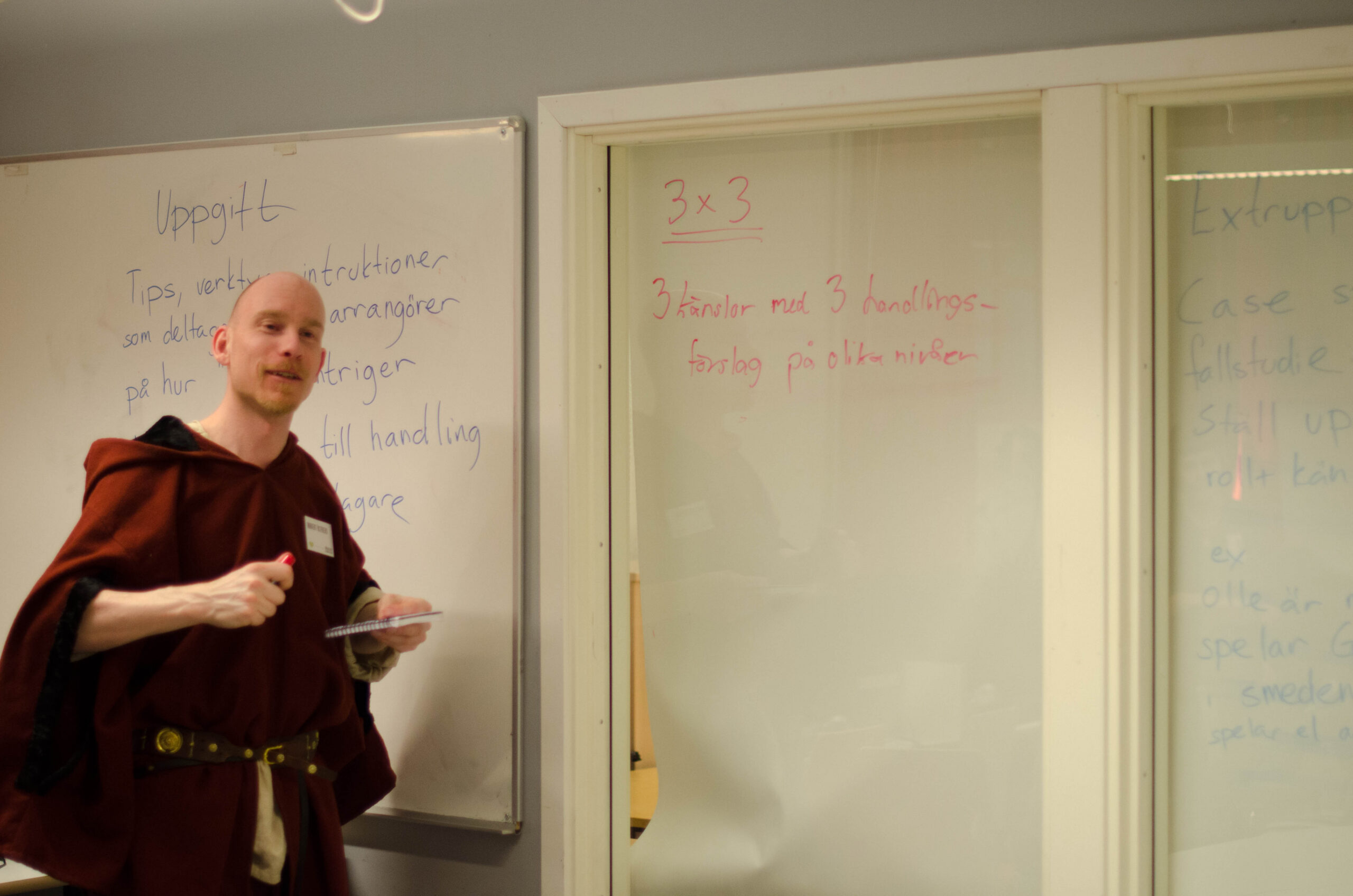

Learning by Playing – Larp As a Teaching Method

in

Tell me, and I will forget.Show me and I may remember.Involve me, and I will understand. Confucius The next generation of teachers will be expected to possess a broad spectrum of competencies and skills. They are faced with a seemingly impossible task: today, classroom instruction should teach not only content but also competence. It should