Category: Documentation

-

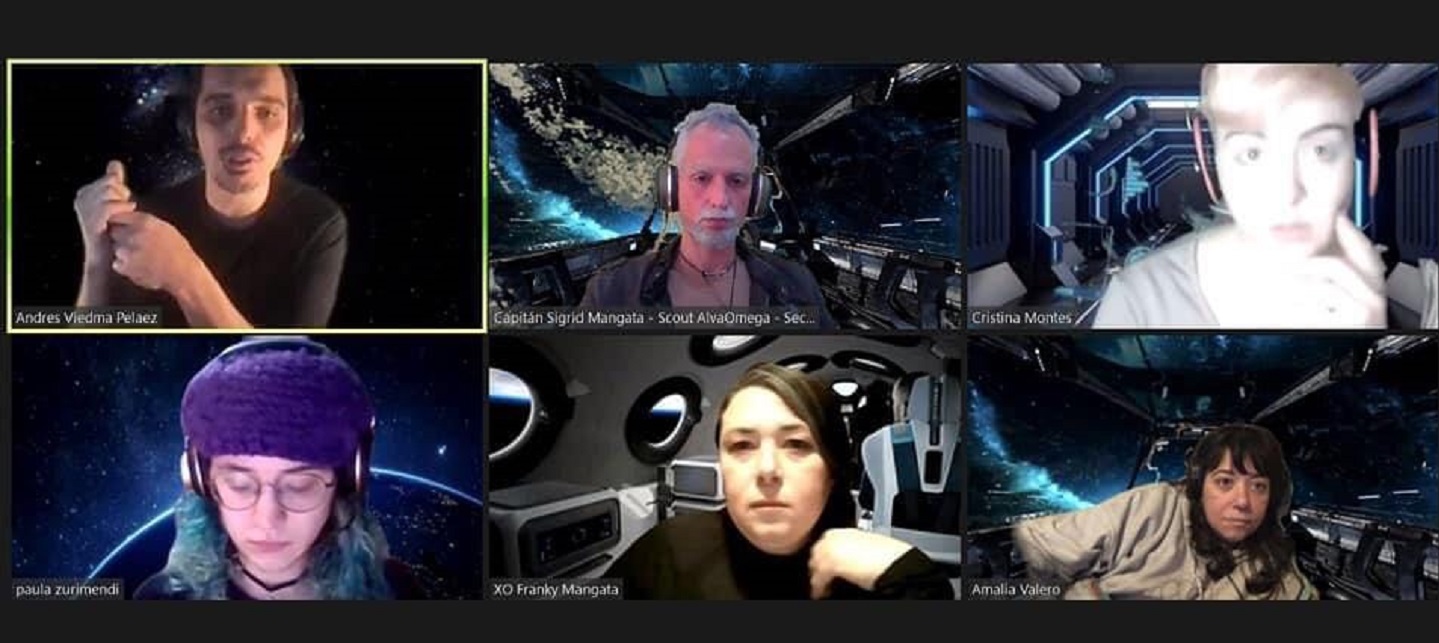

The Online Larp Road Trip

The pandemic was catastrophic for physical larp but also acted as the catalyst for the development of online larp.

-

Culture, Community, and Layers of Reality: Playing Allegiance

A pervasive larp about the Cold War and the diplomacy needed to stave off nuclear Armageddon.

-

Pandemic Larp Improvisation

Larp organizers have learned a thing or two about organizing scenarios. How have we applied those skills during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

Documentation of Larp Design

Eight types of design-relevant larp documents with different purposes aimed at distinct audiences.

-

Dance Macabre Blueprint

Detailed explanation of the design and organization of the Dance Macabre larp, in which pairs of dancers attempt to overcome problems and fears around the subject of love.

-

Czech Chamber Larp Through the Years, Part 2

The second part of an article surveying the history of Czech and Slovak chamber larp.

-

Czech Chamber Larp Through the Years, Part 1

The first part of an article surveying the history of Czech and Slovak chamber larp.

-

Through Someone Else’s Eyes: A Confession

As an in-game larp photographer, it is indeed possible and maybe sometimes even desirable to let your character take over.

-

Dragonbane Memories

We had crazy plans. We would transform fantasy larp forever. We would create the best larp in the world… or so I thought.