Category: Documentation

-

Hinterland: Playing to Really Lose

In the year 2013, the Swedish midsummer idyll is shattered to pieces when Russia suddenly attacks. A war without winners commences, followed by the deadly epidemic called Rosen (the Rose). In refugee camps around the country, tens of thousands die from starvation, violence and sickness. Three years after that first fatal bombing night, the gates

-

Hinterland: Design for Real Knives and Misery

Hinterland was a Swedish post-apocalyptic larp about refugees and disease. It was language-neutral, in effect meaning that people did their best to switch to whichever language was most inclusive for the players present in any given scene. What follows is my personal take as a player on some aspects of its design, and in particular…

-

The Last Ropecon at Dipoli

Ropecon is a Finnish roleplaying game convention. It’s also been something that’s been a part of my life for twenty years now. It was first organized in 1994, but I missed the initial years. I’m pretty sure my first Ropecon was 1996. I was sixteen and had just discovered Werewolf: the Apocalypse. I had made

-

Tonnin Stiflat: Season One – To Booze or Not to Booze…

Setting Helsinki in the 1920’s: urbanization, the admiring gaze towards Europe; jazz and lipstick, daring women entering the public sphere; a country divided by the bitter civil war in 1918; prohibition and the tsunami of illegal alcohol and booze-related crimes. The perfect setting for a larp, and as Niina had published two novels set in

-

The Golden Cobra Challenge: Amateur-Friendly Pervasive Freeform Design

Once upon a time – actually, at GenCon 2014 in Indianapolis, USA – several of us discovered a design problem for live freeform games. For the last five years, the independent role-playing game scene here in North America has run an expanding series of crowdsourced events under the banner of Games on Demand. Players show…

-

Ticket to Atlantis – Fear, Love, Death, Life…

Atlantis is a small town in Washington, USA. It’s surrounded by woods, has no phone line, and the mail service works poorly. The only way to come there is by the railway, and the train is the only way to leave. The ticket office is closed, and the quizzical Conductor (somewhat resembling O. G. Grant)

-

Baltic Warriors Tallinn

I work as a larp producer in the Baltic Warriors project, and first game of our summer season was played last Saturday in Tallinn. It’s quite intimidating to go another country to do a game there. I had never even played in an Estonian larp, but it seemed to go well. This summer, we’re doing

-

Skoro Rassvet – Vodka, Tears and Dostoyevsky

Man will vanquish by his will and reason over the nature. He will understand that he is mortal that he has now hope for resurrection and he will accept death and he will accept it with satisfaction. He will be as God and eve- rything will be allowed to him and as soon as man

-

Salon Moravia – Cabaret for Women Only

The door shut and he was gone. At that moment, Evžénie forgot his rank. But she would never forget his short moustache waving over her, how the lips under it were feverishly mumbling something in that repulsive language. How he snorted when he humped. She slid down to the floor. Her back against the wall,

-

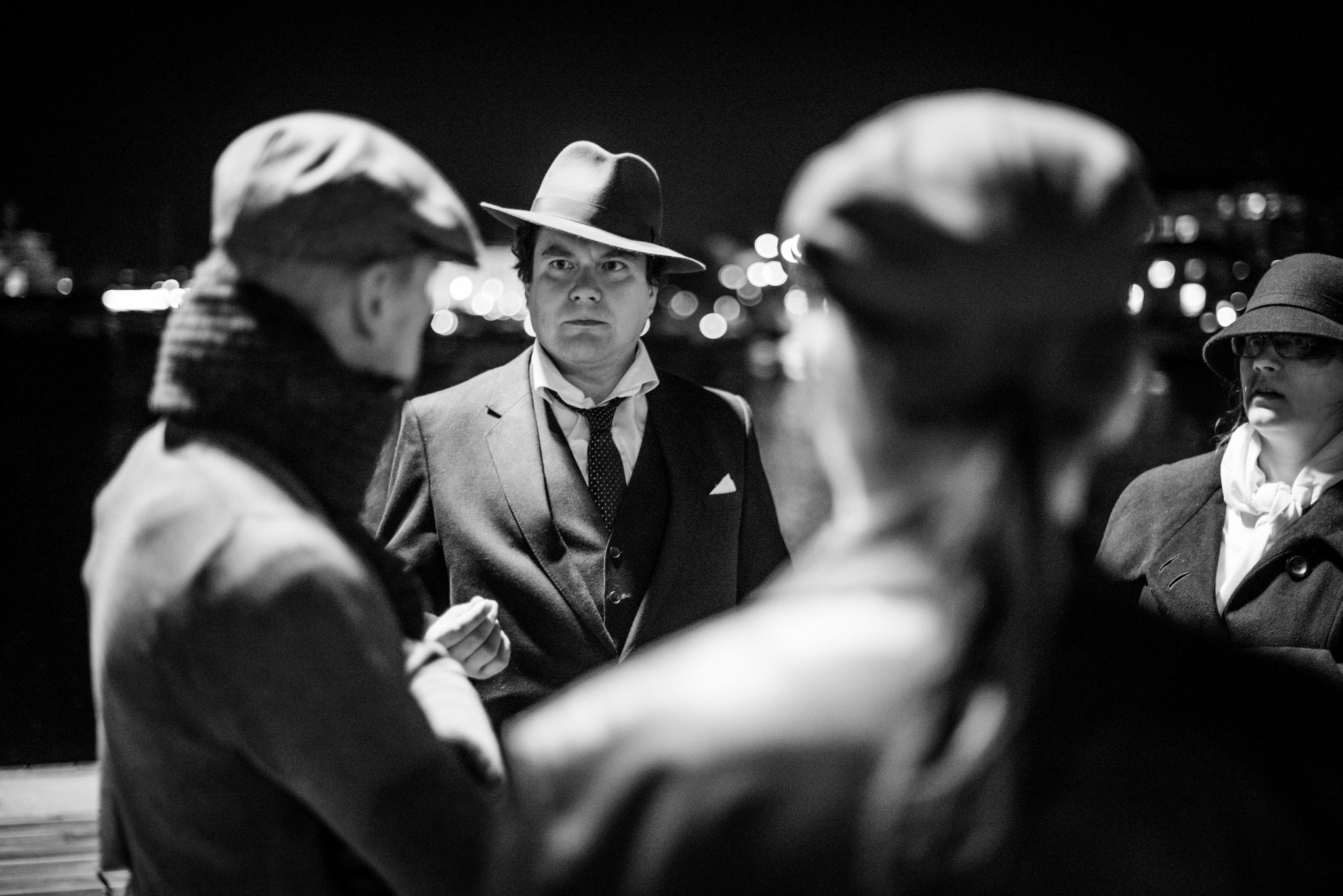

Murder in Helsinki

Tonnin stiflat is a Finnish larp campaign played in Helsinki in 2014. Consisting of three games, it was organized by the veteran city game designers Niina Niskanen and Simo Järvelä. The setting is Helsinki in the year 1927, and the subject matter crime, prohibition, working class life and the violent legacy of the civil war.