Tag: The Knudepunkt 2015 Companion Book

-

Looking at You – Larp, Documentation and Being Watched

So far, Nordic larp has produced two games that have become international news stories that all kinds of sites cannibalize and copy from each other: the Danish 2013 rerun of Panopticorp, and the Polish-Danish Harry Potter game College of Wizardry. In both cases, the attention was fueled by solid documentation and good video from the

-

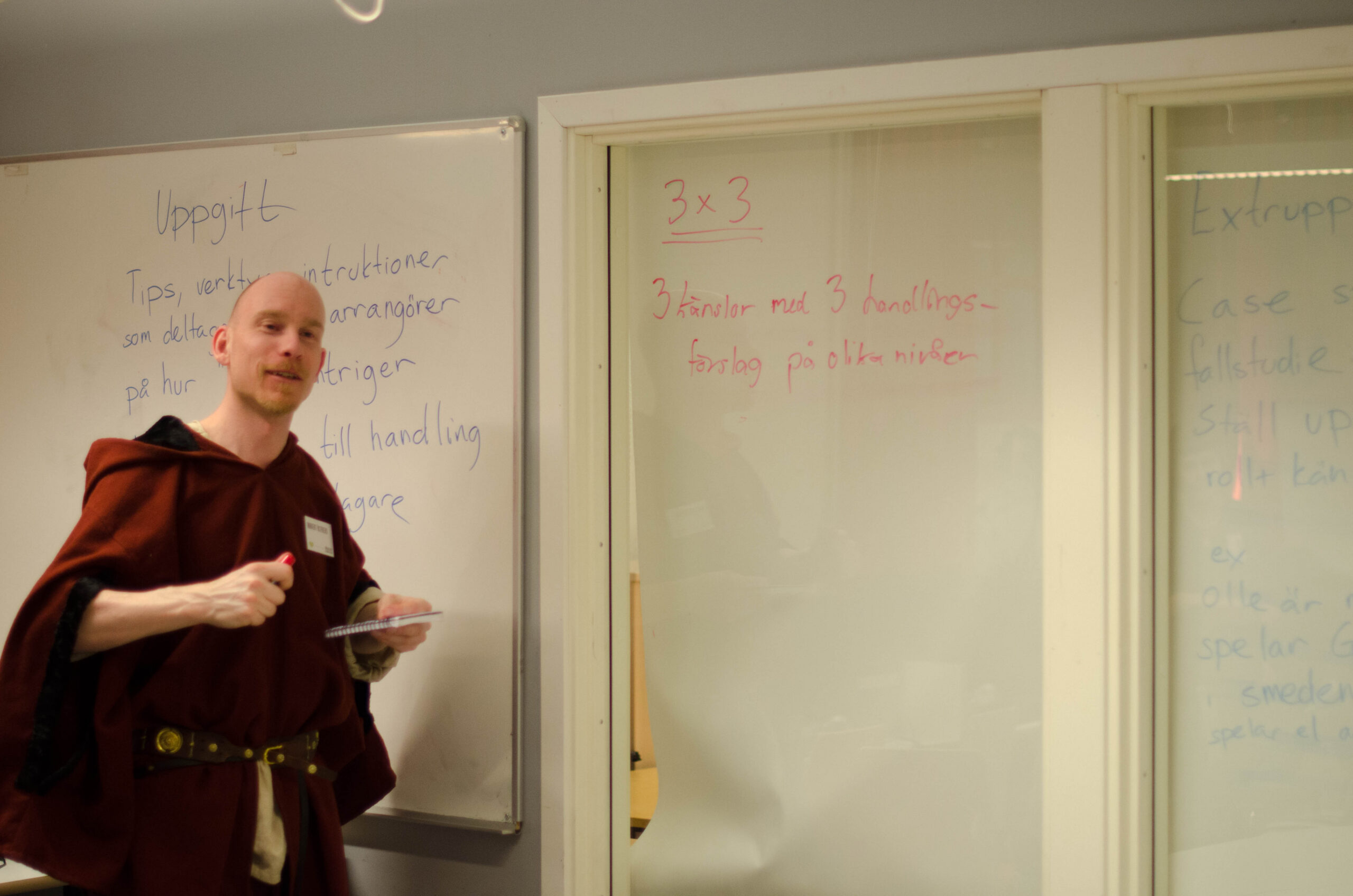

Learning by Playing – Larp As a Teaching Method

in

Tell me, and I will forget.Show me and I may remember.Involve me, and I will understand. Confucius The next generation of teachers will be expected to possess a broad spectrum of competencies and skills. They are faced with a seemingly impossible task: today, classroom instruction should teach not only content but also competence. It should

-

Ingame or Offgame? Towards a Typology of Frame Switching Between In-character and Out-of-character

in

For the Moscow and St. Petersburg larp communities, continuous immersion into the game and into the character seems to be the central point of the larp process. Larp rules proclaim continuity of game, and players generally disapprove one’s going out of the character while playing. This attitude is, however, more declarative than a reflection of

-

Infinite Firing Squads: The Evolution of The Tribunal

I accidentally created a hit, and have ever since been wondering why. I have had success with several mini-larps over the years, such as A Serpent of Ash (2006) and Prayers on a Porcelain Altar (2007), both of which keep getting the occasional rerun here and there. The Tribunal, however, is something else. It has

-

Four Backstory Building Games You Can Play Anywhere!

One of the most difficult – but also most rewarding – parts of larp is coming up with a good character backstory. A sense of a character’s past gives great insights into how to play them in the present, for one thing; not to mention, it shines some light on where you may take them

-

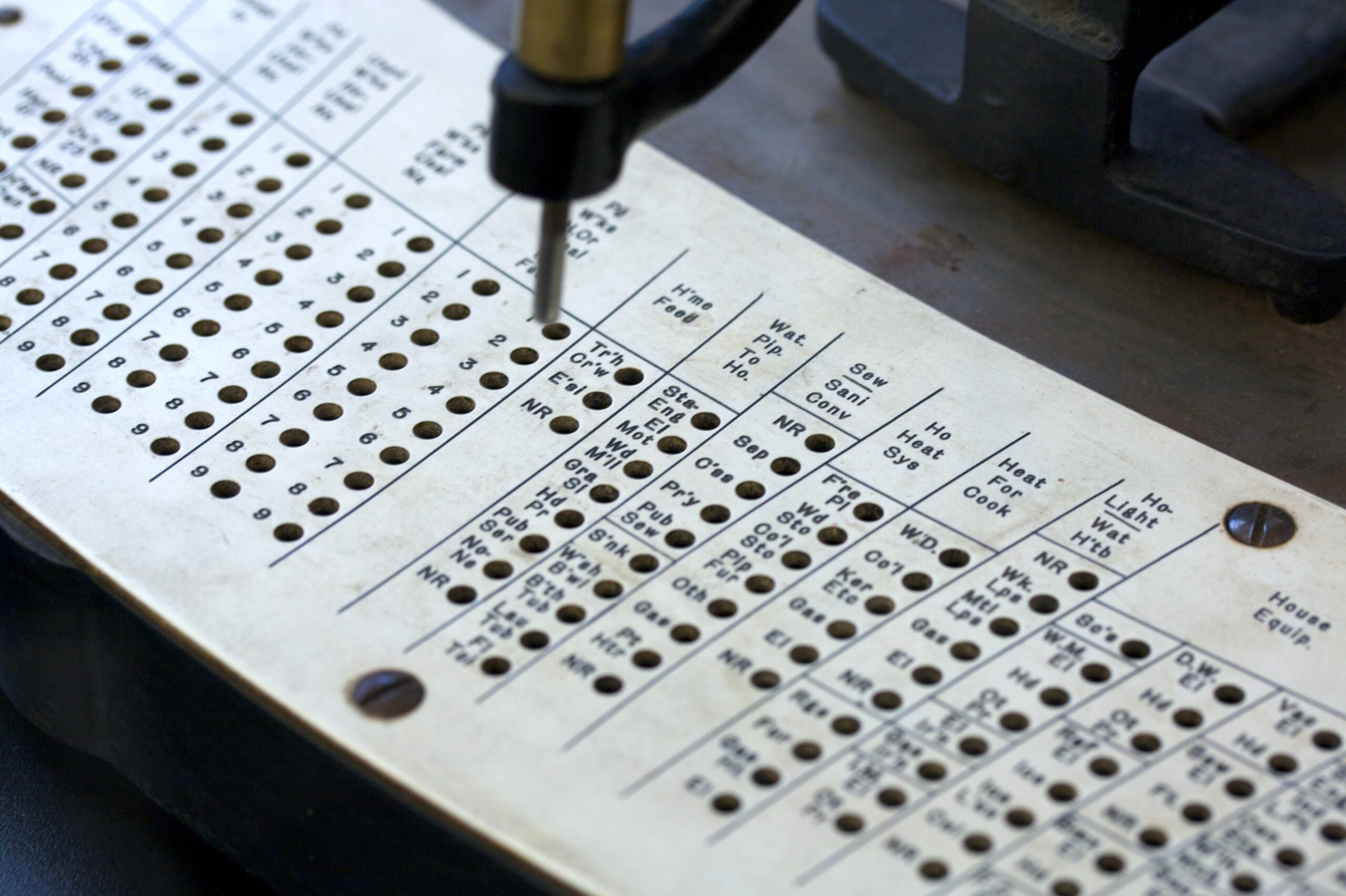

Behind the Larp Census

29.751 larpers can’t (all) be wrong On January 10, 2015, 101 days after launching, the first global Larp Census closed to replies. 29,751 responses were logged from 123 different territories in 17 different languages. The data from this survey is freely available via a Creative Commons license at LarpCensus.org. Barring death, dismemberment, or debilitating drunkenness, the total

-

Six Levels of Substitution

in

The Behaviour Substitution Model You are gliding over the parquet, in a constant battle over who’s in charge. You lock eyes and tighten your grip pulling your partner just a bit closer. Your posture and precise footwork radiate confidence. Other players are holding their breath to see which one gives up the battle first. Actually,