Tag: organizer safety

-

All Quiet on the Safety Front: About the Invisibility of Safety Work

in

Most players and some organizers might not know what the experiences before, during and after a larp are like for safety people.

-

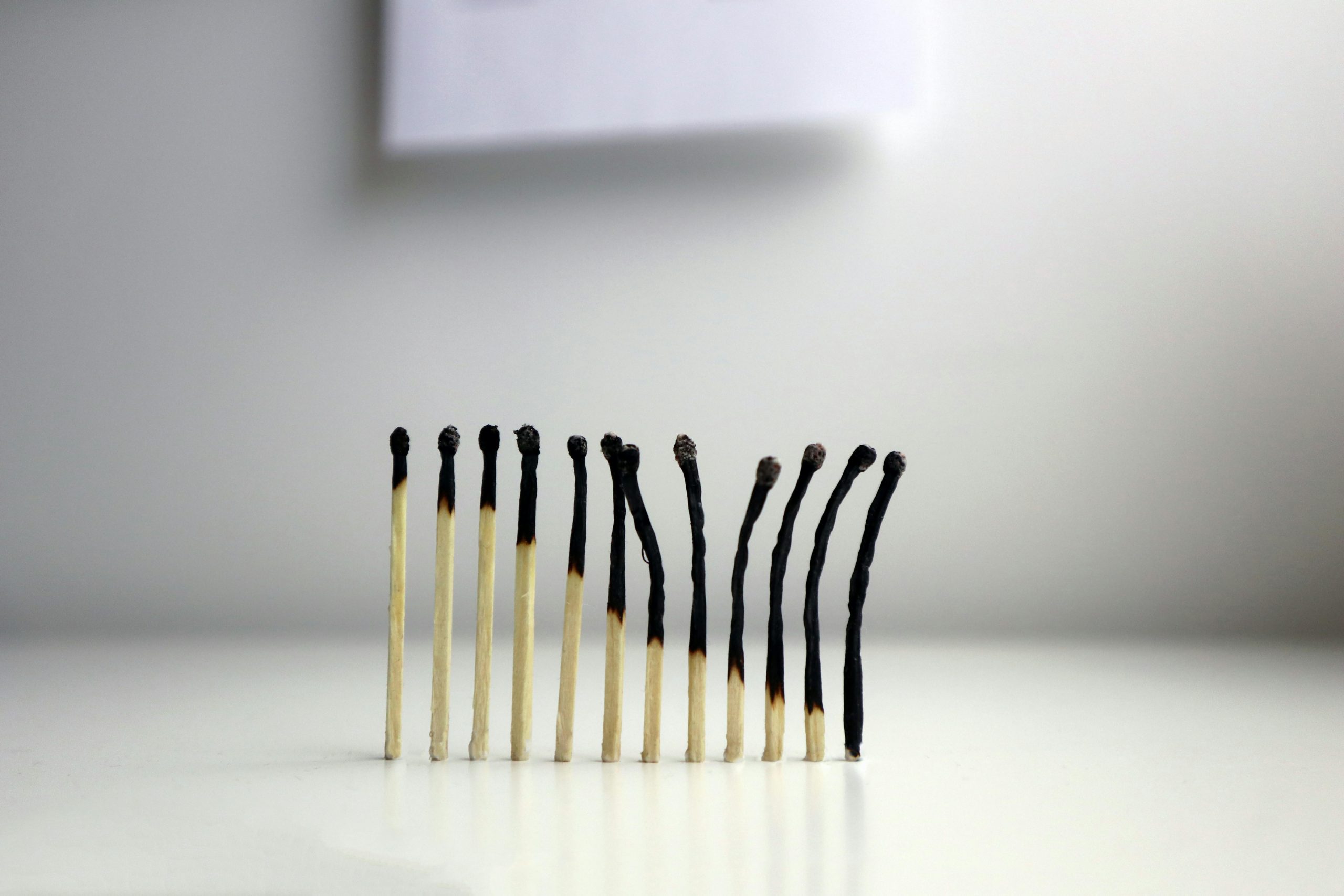

Please Stop – an Occupational Therapist’s Advice on How to Avoid Burnout

in

A newly working occupational therapist, larper, larp creator and two-time burnout survivor gives you some real-life tips and tools to fight back against burnout.

-

Basics of Efficient Larp Production

in

An alternative mode of production to the Infinite Hours of labor often spent in larp organizing and volunteering.

-

Leaving the Magic Circle: Larp and Aftercare

in

The transition from larp to everyday life can be messy sometimes. Some thoughts on aftercare in a larp context: how to do it and why.

-

How to Take Care of Your Organizer

in

This article offers ways that players can take care of their organizers to help people avoid burning out and becoming discouraged from running larps again.