Tag: Knutepunkt

-

Open Book: A Roadmap for Peer Editing

An explanation and discussion of the process by which 67 people came together to make the Knutepunkt 2025 book Anatomy of Larp Thoughts: A Breathing Corpus.

-

Nordic Larp is not ”International Larp”: What is KP for?

in

International larp is a tremendous thing, and it deserves to thrive and grow. But not at the expense of the Nordic larp that it borrows so heavily from.

-

Knutepunkt 2021 Call for Papers

in

Knudepunkt 2021 has issued a call for papers! Pitches are due 10 July 2020 and the theme of the conference, and book, is “Where the magic happens”.

-

Wyrding the Self

in

Wyrding the self is the sustained effort to decolonize your body from the mythical norm, and begin the process of identity alteration.

-

Know Yourself

in

Once you understand what you can and can’t do, want and don’t want to do, it becomes easier to have good larp experiences and to co-create them with others.

-

Emotions as Skilled Work

in

This text is focused on the social and cultural aspects of emotion work and on our understanding of the skills involved in the context of larp.

-

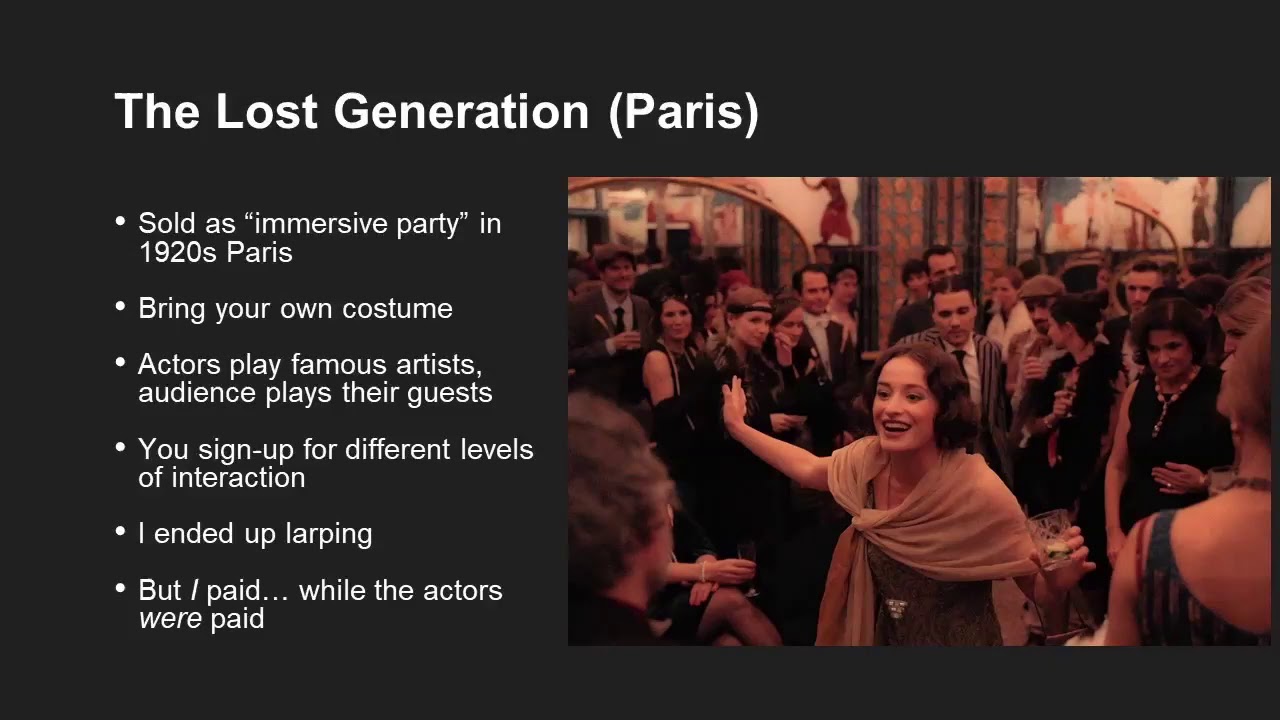

Solmukohta 2020: Is Immersive Theatre the Future of Larp?

Thomas B covers some larp-like events. Mélanie & Michael co-wrote The Lost Generation, an immersive theatre party focused on seamless narrative design.

-

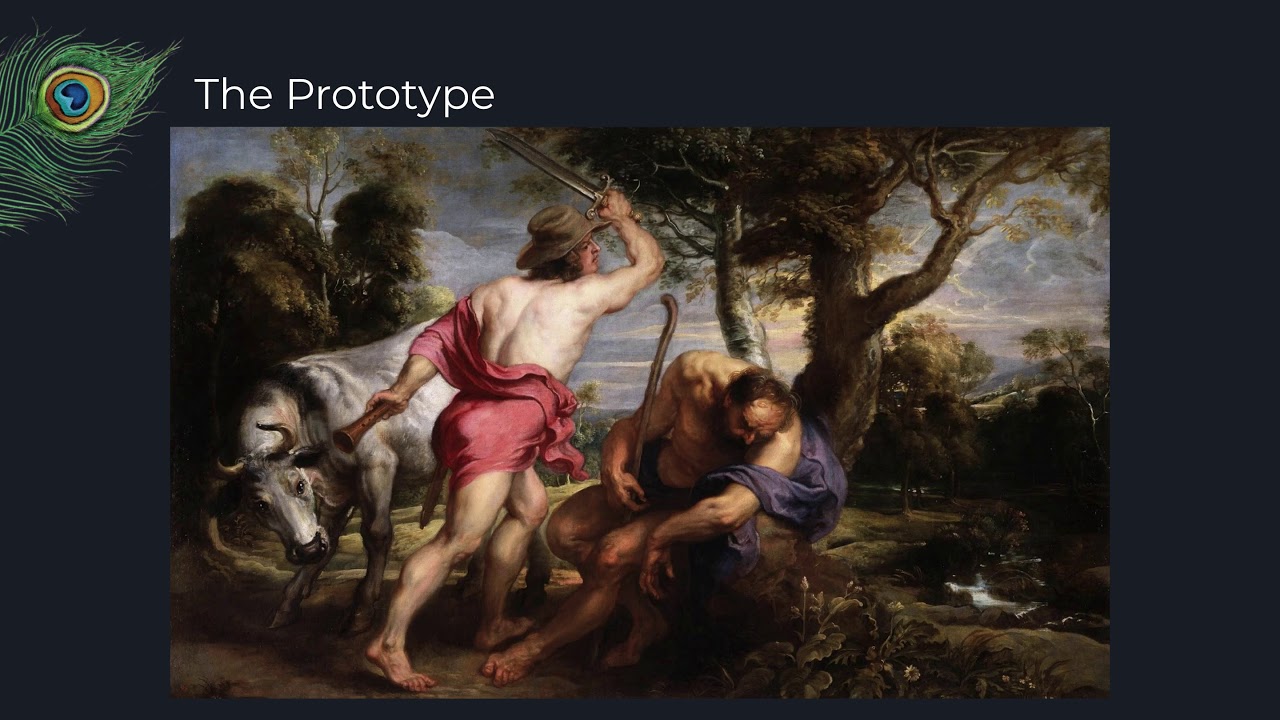

Solmukohta 2020: Chris Bergstresser – Peacock – a Global Larp Clearinghouse

A proposal, and a prototype, for a larp clearinghouse named Peacock. It includes standards for larp data and a website to share that information.

-

Solmukohta 2020: 500 Magic Schools for Children and Youth

This panel brings together NGOs, companies and other entities that run magic schools for kids and youth; presenting themselves and their work.

-

Solmukohta 2020: Lindsay Wolgel – Larp/Theatre Crossover in NYC

A talk about the larp/theatre crossovers currently emerging in NYC, based on projects Lindsay has been part of in the past year as a professional actor.