Tag: Italy

-

Rebels on the Mountain – The Last Night of Montelupo

The Rebels on the Mountain was a larp played in Italy in 2015. It was the first historical larp of Terre Spezzate, a larp group active in northern Italy.

-

The Legend of Percival – Larping in Babylon

In September 2015, in the city of Rome, the Chaos League organized The Legend of Percival; a pervasive larp with participants playing outcasts.

-

Introduction to Southern Way – New Italian Larp

in

In recent years Larp has gained strength and popularity in Italy, and has taken new and more conscious forms. This Manifesto suggests a path for this process, and continues by defining Larp as a strong, actively engaged way of telling stories. Powerful stories that leave their mark. Stories that are hatchets waiting to be dug…

-

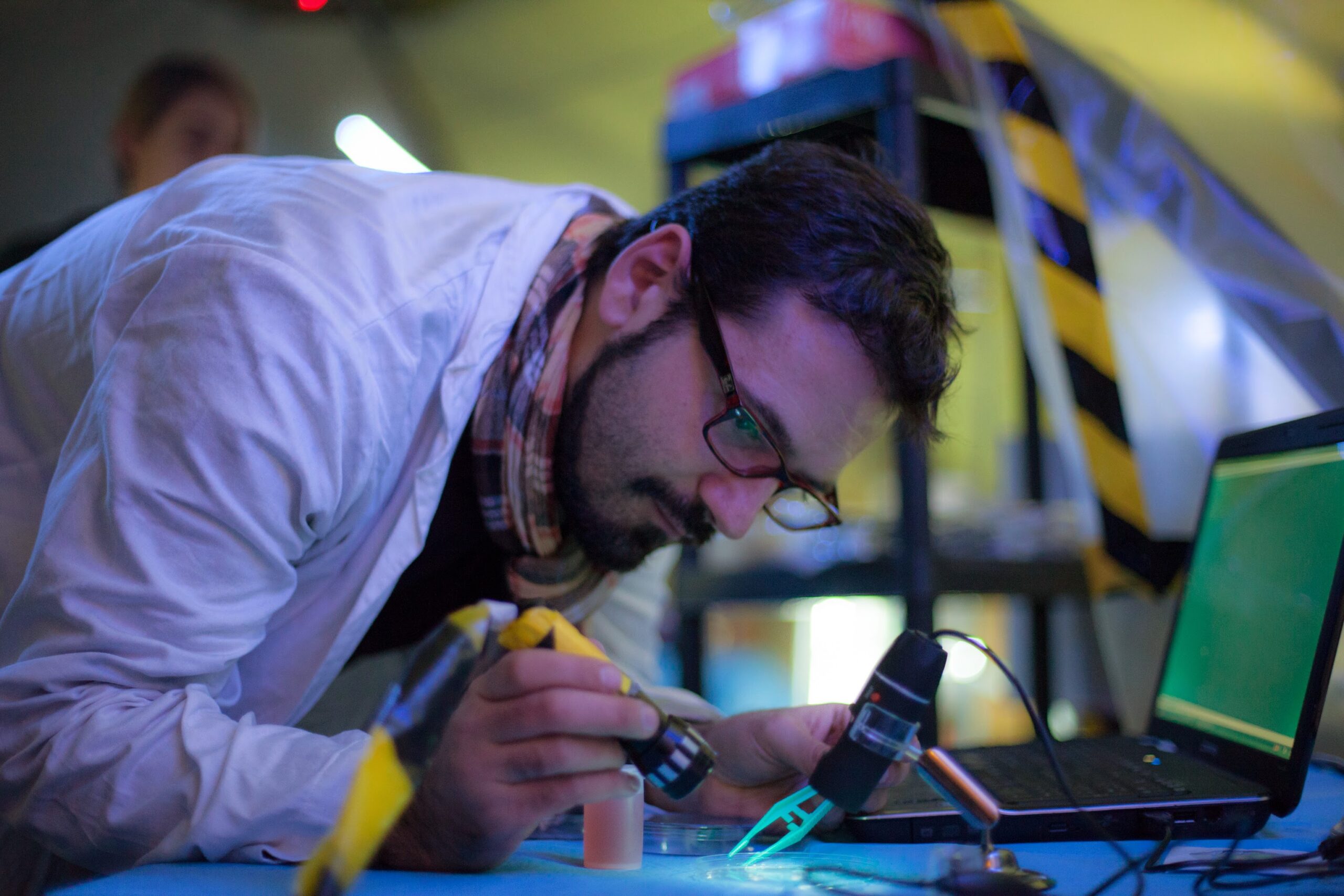

The Whole Is Greater than the Sum of Its Parts – Voices from Black Friday

In this larp we didn’t have restrictions. We just wanted to organize the coolest larp ever played in Italy. At least, that’s what I wanted.Chiara Tirabasso, Black Friday larpwright Chiara Tirabasso is one of the many larpwrights behind Black Friday. She perfectly sums up two elements of the organizing team: a great ambition on quality