Tag: Bleed

-

Larp Crush: The What, When and How

in

Larpers generally agree that what happens in-game stays in-game. But then there’s the larp crush — a condition where you and your character get your wires crossed, so to speak. Larp crushes are known to be potentially more intense than pretty much any other experience of bleed.

-

The Battle of Primrose Park: Playing for Emancipatory Bleed in Fortune & Felicity

Fortune & Felicity was an opportunity to immerse into a world, explore my academic interests, add to my fieldwork, and experience emancipatory bleed.

-

Pre-Bleed is Totally a Thing

in

Pre-bleed is the experience of emotional bleed prior to ever playing the character in a larp setting. This paper considers pre-bleed before College of Wizardry 5.

-

Tears and the New Norm

in

In recent years, we — the Nordic/International progressive role-playing scene, both tabletop and larp — have produced games that can bring out powerful emotions in the players, and empower the players to engage with powerful emotions. This process has significantly extended the artistic reach of the role-playing medium, and also given a lot of people

-

Chasing Bleed – An American Fantasy Larper at Wizard School

This article describes how I felt about my experience as someone who comes from an American campaign boffer fantasy larp background taking part in a Nordic style larp.

-

Bleed: The Spillover Between Player and Character

in

Participants often engage in role-playing in order to step inside the shoes of another person in a fictional reality that they consider “consequence-free.” However, role-players sometimes experience moments where their real life feelings, thoughts, relationships, and physical states spill over into their characters’ and vice versa. In role-playing studies, we call this phenomenon bleed.((Markus Montola,

-

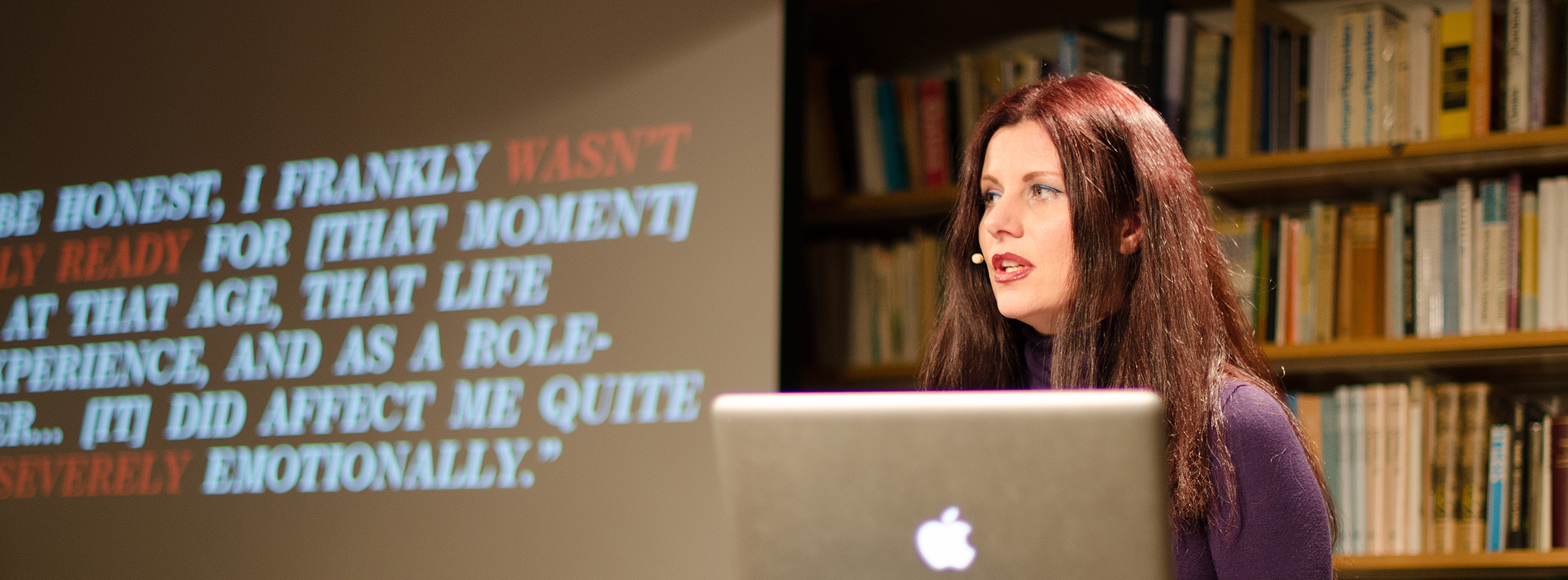

Nordic Larp Talks: Bleed: How Emotions Affect Role-Playing Experiences

This talk explains the concept of bleed in role-playing games & advocates for awareness of the phenomenon & discussion on emotional content in games.