Can 2016 be the year we make a breakthrough on the subject of how to deal with audience at chamber larps?

When attending contemporary theatre performances in the past year, I have been following closely what happens when the actors try to involve the audience in doing something. Even though the audience at these kind of performances should not be alien to some kind of interactivity, the bar seems to be extremely high for people to take part. One example I remember well is when Lisa Lie addressed the audience and invited them to “tap three times” in Blue Motel (Black box Theatre, Oslo, 2015). Not a single spectator responded until she had repeated the request three times, with increasing intensity — and frustration. At last, one spectator simply tapped the floor three times with their shoe, and the show could go on.

The norms of non-participation that separate the audience from the actors in the theatre are extremely strong, at least in Norway. We are afraid of misinterpreting the actor or somehow else making a mistake. Even as a larper I find myself insecure – afraid that a misguided response could ruin the piece. I excuse myself thinking there’s always someone else more qualified than myself to make the response – “The Bystander Effect.” Although the “super-audience” – the people who dare to engage in participation and add the extra flavour to a piece — do exist, they are rare. It seems that providing the safety and alibi necessary for an audience to engage in even the slightest participation is a very difficult hurdle for the artists.

When it’s hard for the actors to get the spectators at contemporary theatre to take part in very simple and limited interaction, how can we as larp designers ever succeed in reaching out to more people than the few brave enough to start out with taking a full-fledged step into the larp as players?

How to reach an audience of spectators has been a headache for chamber larp designers for many years. If we could solve this Gordian knot, it could make larp available to a much wider community and bolster its recognition in other circles of performing arts.

Approaches to the Audience Problem

Video

One of the few people who have both legs inside the art circles and are working with larp, is Brody Condon. He uses larp techniques to create improvised action. One of his pieces is The Ziegarnic Effect , which was exhibited at the Nordic Biennial of Contemporary Art in Moss this summer. To sum it up in two sentences, it was a larp-like roleplay with eight players, taking place in a house while being live broadcast via video link for two days. After the first two days, an edited version of the video was on display.

Brody told me that in his eyes, what he did was at least three pieces: one piece was the edited video showing during the entire exhibition, another was the live video stream, and the third was the roleplay itself.

From a larp perspective, the latter piece clearly is the most interesting. But for the outside world, it is the video pieces that count, mainly the edited one., partly because that is a format people are used to, but of course mainly because those are the only pieces that are actually available to them. Brody reached his audience with two video pieces, – but in the end, those pieces were not larps, but video installations showing a film of improvised action. The larp piece itself remains an experience that only truly reached the eight players.

Participate, Don’t Play

With the development of black box larp, the larp scene has also seen an increased liaison with people from theatre and other performing arts. While the first black box larps could be seen as a step backwards in terms of accessibility, the genre has increasingly experimented with ways to make participation just as easy as being an audience at other regular kinds of performing arts.

One way of doing this has been by moving away from seeing the target group as players, but rather as an audience in a participatory piece. Plays belonging to this school are minimizing preparations and rather focusing on creating a playing area that facilitates interaction and shapes characters while playing. The Nyxxx Collective in Stockholm are among the people who have explored this borderland between larp, theatre, and performance art the most. In his keynote talk at Knutepunkt, Gabriel Widing, one of the Nyxxx members, described immersion as “the excrement of action,” noting that if you succeed in changing the behaviour of people, they will eventually immerse. A handful of larps have followed this approach to solve the audience problem.

The Temple of the Blind Beings (2013) is one example. Here, the participants were blindfolded and, after a very brief introduction, entered into a room filled with scenography for tactile interaction. The players could enter or leave at any time, removing the need for a common start and ending.

In Inside Myself Outside Myself (2014), the participants walked into a black box without any preparations and started to explore objects and non-player characters that it was easy to interact with. This worked very well when I played it, but I am not sure how it would work with only non-larper participants. However, an inexperienced player group would probably work well if there were a few instructed players with larp experience as bellwethers in the group. The bellwethers could pave the way and, by taking space, reduce the anxiety that one’s actions would be “wrong.”

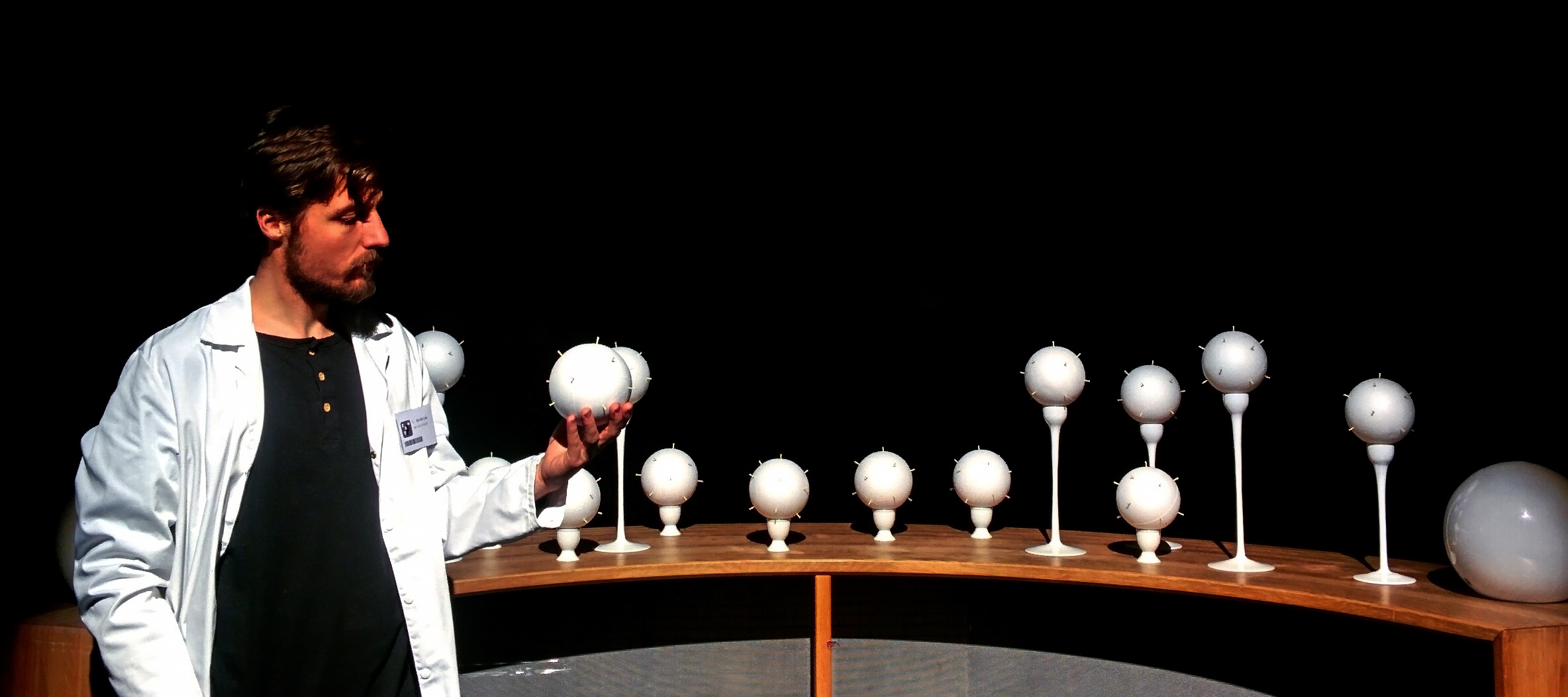

Pieces of You, Pieces of Me (2015) labels itself as a participatory experience. In short, the story is that you will have your personality upgraded to something better. It’s similar to Inside Myself Outside Myself as the players enter the playing area almost without preparations, and their actions and characters are shaped in the “playground for interaction.”

Pieces of You, Pieces of Me at Stockholm Dramatiska.

All these three examples are lowering the practical bar for taking part by removing preparations that can often be demanding and require larp experience. Furthermore, they attempt to lower the psychological bar by not expecting the participants to play a character, but rather allowing them to be just participants who explore an area on their own terms. The question remains to be answered if this approach is enough to lure the participation-anxious (at least in Norway) performing arts audience to join in.

Consecutive Plays

Another way to address the audience problem is to have repeated runs of the same play, preferably in a theatre. This approach subscribes to the view that in a larp, the audience and players are the same people. Instead of changing the content, the framework and setting is adapted to make the audience feel safe even though they are actually players.

Consecutive plays is something we are used to from theatre plays, and it could lower the bar for taking part because as the show runs, more and more people will talk to someone who have already tried it.

I have been hoping to see this for a long time, and while I am not 100% sure it’s the first example, I was delighted to see that Jamie Harper is running eight consecutive runs of The Lowland Clearances at the Camden Theatre in London in January 2016. I am fortunate enough to be joining their dress rehearsal and I’m excited to see how this project will go.

Integrated Audience

One of the most interesting approaches I’ve seen to the audience problem was at The Fragile Life of Souls Gone Missing at Blackbox Copenhagen last month. There are at least a handful of predecessors where audience “play” audience/spectators, such as A Mother’s Heart, where the larp is about a trial and you can be a spectator to the trial. There are also theatre plays where the audience can move around the site with the actors – such as the Punchdrunk plays Sleep No More or The Drowned Man, – but although labelled “interactive theatre,” the audience does not have any role in the fiction and thus not any agency for true interaction.

I think The Fragile Life of Souls Gone Missing combined the two in a very elegant way. In this larp, the players are souls that are looking for their mission or purpose, but forever going in circles. The spectators were given a short introduction before entered into the playing area. In the fiction, they were explained as deities. Contrary to the players, the spectators were not required/expected to interact, but they were given the opportunity to do so. Furthermore, the way they could interact was clearly sketched out by specific phrases the deities were allowed to say and specific actions they could do. On the other hand, the players were given the choice of playing along or disregarding the audience.

This made a clear distinction between the players and the audience and provided the audience with a solid alibi for interaction as well as non-interaction. The opt-in mechanism for the audience and opt-out mechanisms for the players provided a safety net that should prevent any action that could ruin the larp, and hopefully prevent most of the anxiety of doing so. I believe the alibi should be solid enough even for the “regular” participatory-anxious crowd.

Will We Solve the Audience Problem?

Early pioneers have given us signposts for different ways to approach the audience problem, and it also seems like the black box scene is growing up – such that, after the first years of euphoria over the format itself, we can focus on making more people able to try out what we create. I believe 2016 has the potential to be the year when this scene makes a breakthrough for the audience problem of chamber larps.

Thanks to Magnar Grønvik Müller, Eirik Fatland, Jaakko Stenros and Karete Jacobsen Meland for comments.

References

- A Mother’s Heart (2010). Christensen, Christina and Fatland, Eirik. Larp.

- Blue Motel (2013/2015). Lie, Lisa. Theatre performance.

- Drowned Man, The (2013). Punchdrunk. Theatre performance.

- Fragile Life of Souls Gone Missing, The (2015). Essendrop, Nina Runa. Larp.

- Inside Myself, Outside Myself (2014). Björkne, M, Burns C, Dumstrei N, Durkan M, Essendrop N, Holm-Andersen M, Karlsson P, Kiraly Thom, Munthe-Kaas P, Nilsson G, Nøglebæk O, Ryding K, Widing G. Larp

- Lowland Clearances, The (2016). Harper J.

- Pieces of You, Pieces of Me (2015). Grønvik Müller M, Pierpaolo V, Nordblom C, Dolk C, Brown M. Larp.

- Sleep No More (2011). Punchdrunk. Theatre performance.

- Temple of the Blind Beings (2013). Larp. Peter Munthe-Kaas.

- Zeigarnic Effect, The (2015). Larp/video installation. Brody Condon

Cover photo: Pieces of You, Pieces of Me at Stockholm Dramatiska.